This blog is an excerpt from the Chainalysis 2020 Crypto Crime Report. Click here to download the full document!

Cryptocurrency as a terrorism financing tool presents difficult issues for the intelligence community. Unlike social media profiles and bank accounts, agents oftentimes can’t have a cryptocurrency address shut down due to the decentralized nature of blockchains. While knowledge sharing is crucial to take on such a dangerous threat, terrorism financing in cryptocurrency is also difficult to report on publicly, as most cases involve sensitive information or are classified for national security reasons.

But despite the difficulties in analyzing this subject, we can say from the investigations we’ve been involved with in 2019 that there’s some cause for concern. What’s especially worrying are the advancements in technical sophistication that have enabled successful terrorism financing campaigns using cryptocurrency. Below, we’ll compare case studies of two such campaigns — one that took place between 2016 and 2018, and one from 2019 — to illustrate these changes.

Looking back: Ibn Taymiyyah Media Center’s 2016-2018 cryptocurrency fundraiser

Ibn Taymiyya Media Center (ITMC) is the media wing of Mujahideen Shura Council (MSC) in the Environs of Jerusalem, a jihadist group based in Gaza and designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization by the U.S. State Department. In addition to producing propaganda supporting ISIS and other terrorist groups, it also publishes instructional materials showing how to make weapons and advocating for terrorist attacks.

In 2016, ITMC became the first terrorist organization to launch a public crowdfunding donation campaign using cryptocurrency. ITMC named its campaign Jahezona (“Equip Us” in Arabic) and explicitly told potential donors the funds they sent would be used to buy weapons. They also advertised the campaign as a way for Muslims around the world to join their cause, citing Koran verses to position donating to the fundraiser as a religious obligation.

The Equip Us campaign ran from June of 2016 to June of 2018. ITMC promoted it on platforms like Twitter, YouTube, and Telegram, posting a Bitcoin address to which donors could send funds. While only a single Bitcoin address was disclosed as part of the campaign, we were able to discover an additional 27 addresses associated with the campaign using Chainalysis Reactor. This provides investigators with a more comprehensive picture of the transactions associated with the ITMC wallet.

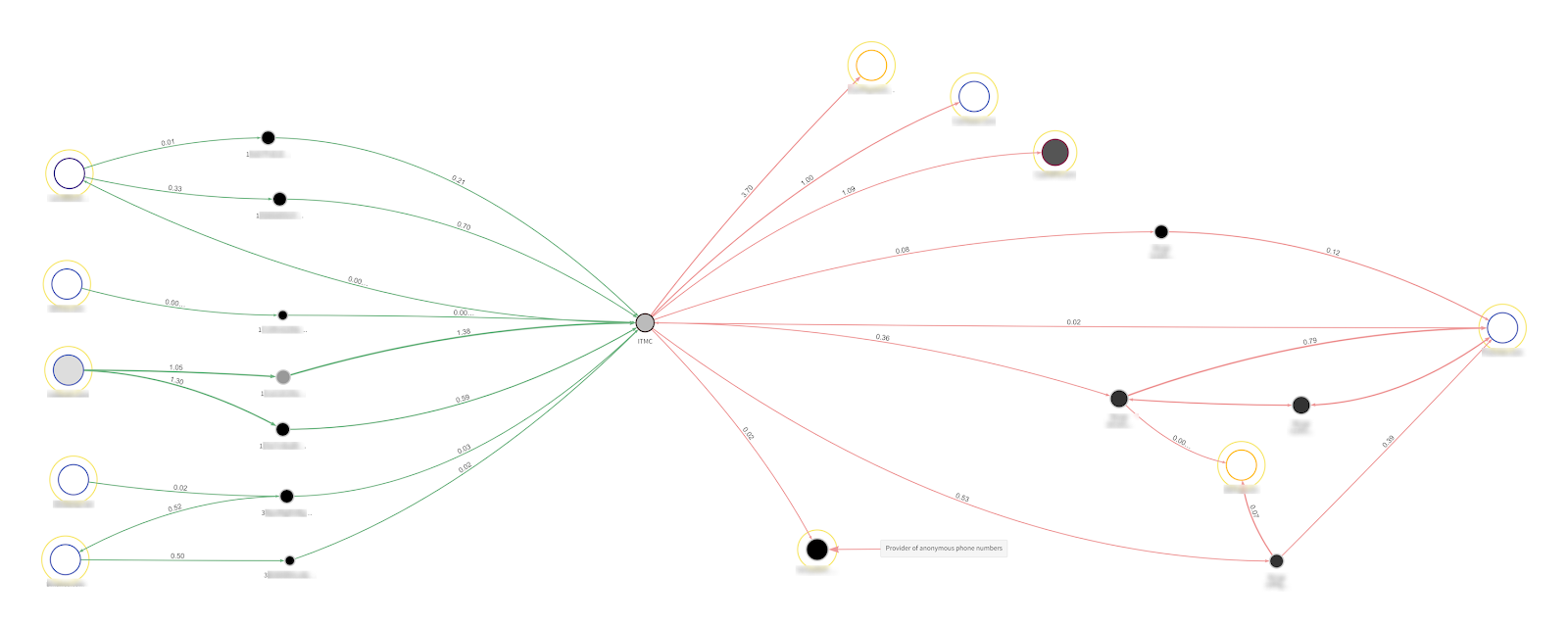

On the left, we see a sample of some of the donations, most of which came in from addresses at mixers, regulated exchanges, or P2P exchanges — in most cases, donations passed from those services to an intermediary private wallet before reaching ITMC. On the right, we see ITMC sending donations to various addresses, presumably to be converted into cash. Interestingly, we also see them sending funds to a wallet we know from Chainalysis’ OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) is associated with a service that sells fake phone numbers in bulk. Many extremist groups purchase these phone numbers in order to create new social media accounts when old ones are banned — that may be what’s happening here.

Let’s take a closer look at the donations themselves.

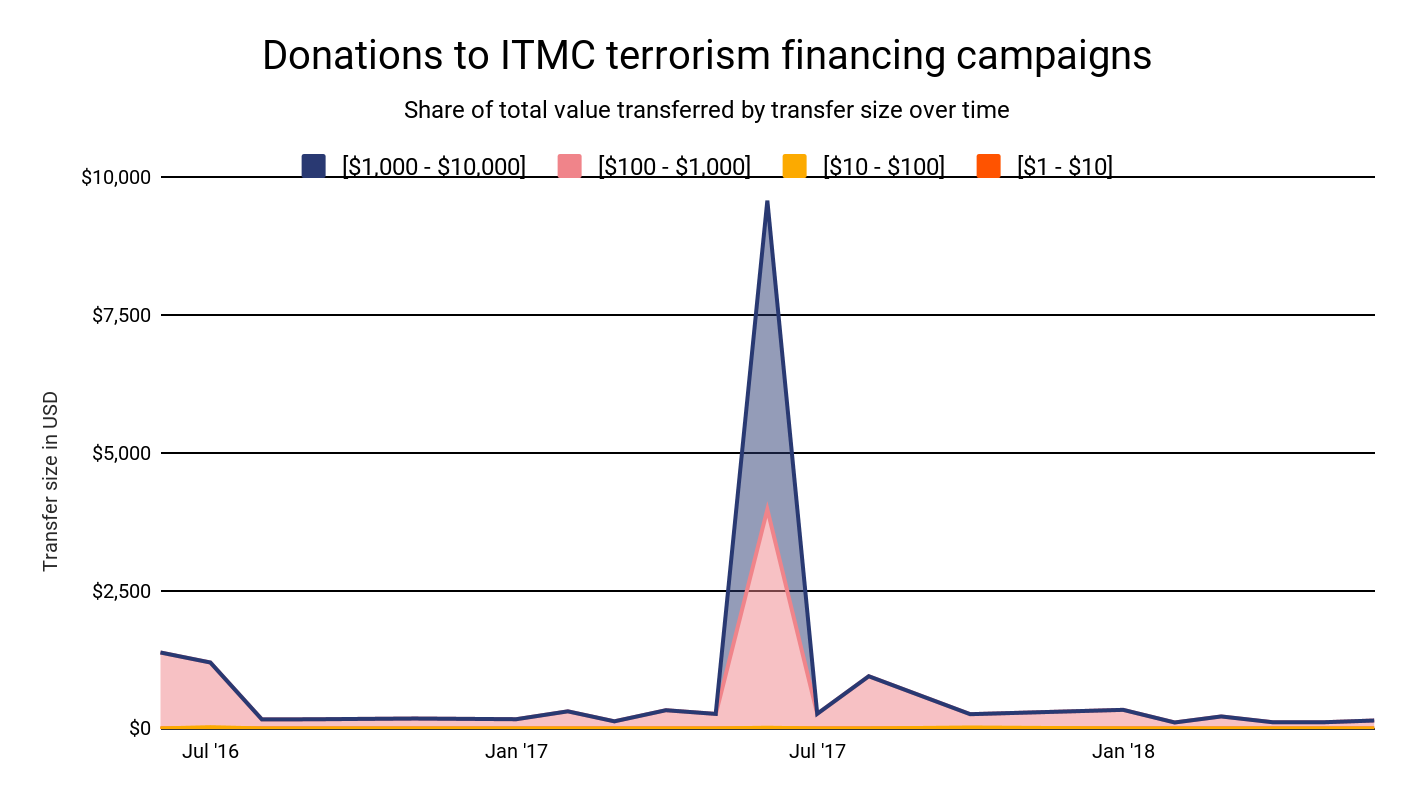

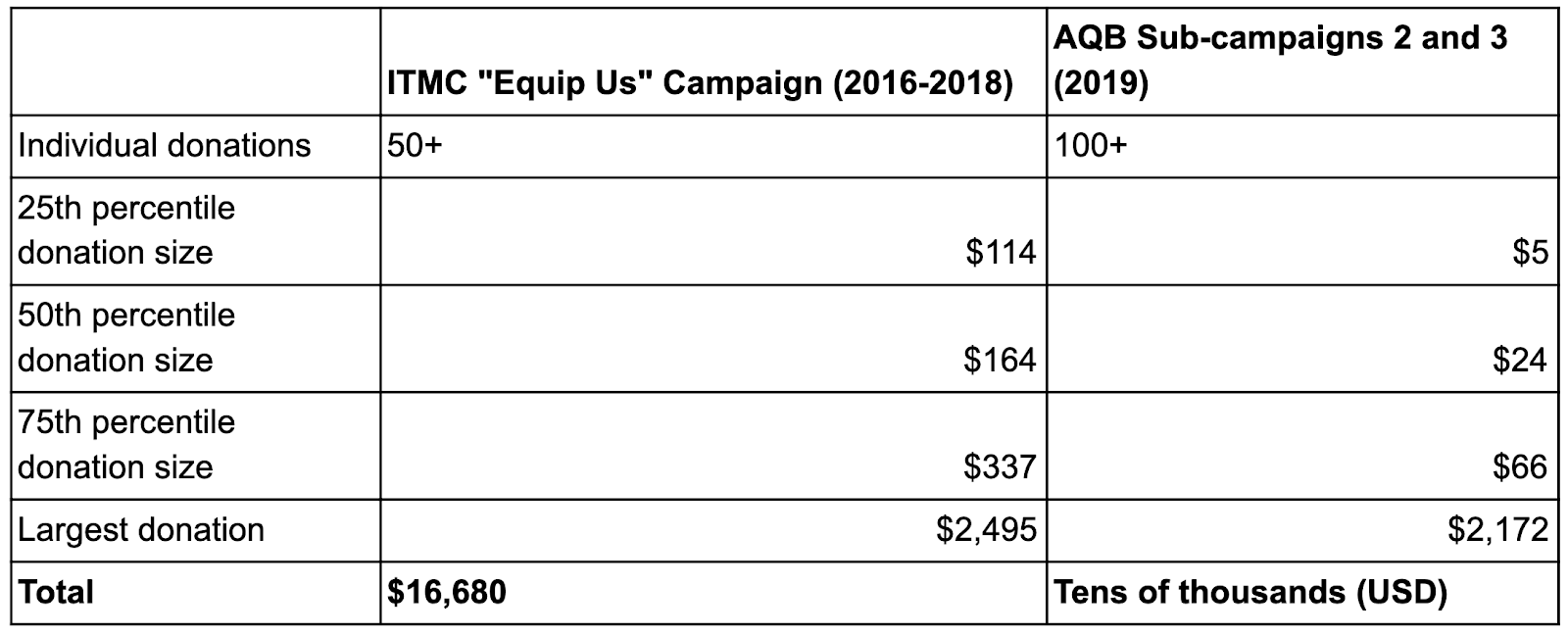

Over the two years the fundraising campaign ran, ITMC received tens of thousands’ worth of cryptocurrency across more than 50 individual donations, with a notable spike in June 2017. The median donation size was $164. The single largest donation was just under $2500, and just two other donations topped $1,000. 14% of donations were between $500 and $1,000, and nearly all of the remainder were between $100 and $500, with most of those falling between $100 and $250. We observed just four donations under $100 worth of cryptocurrency.

While that may not sound like much money over a two year period, it’s important to recognize that terror attacks can be carried out cheaply with weapons made from relatively ubiquitous materials. And as we explore below in our case study of Al-Qassam Brigades’ 2019 terrorism financing campaign, other groups have become much more sophisticated in the methods they use to solicit and accept cryptocurrency donations.

Tracking cryptocurrency’s biggest ever terrorism financing campaign

In early 2019, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades (AQB) — the military wing of Hamas and another designated terrorist organization — began soliciting donations in Bitcoin in one of the largest and most sophisticated cryptocurrency-based terrorism financing campaigns ever seen. AQB utilized multiple types of wallet infrastructures to receive donations before settling on a system that generated a new address for every donor to send funds to, the first verified example we’ve seen of such technology deployed by a terrorist organization. To date, the campaign has generated tens of thousands of dollars of Bitcoin for AQB.

Investigators and analysts are currently using Chainalysis to analyze these transactions, which could enable them to discern the origin of the donations and the destination of funds received by AQB during the campaign. This ultimately could help them identify the donors and financial facilitators at AQB who are running the campaign. While this investigation is ongoing, we can share some insights into this campaign based on Chainalysis data to show you how today’s terrorists are utilizing cryptocurrency.

How AQB solicited cryptocurrency donations

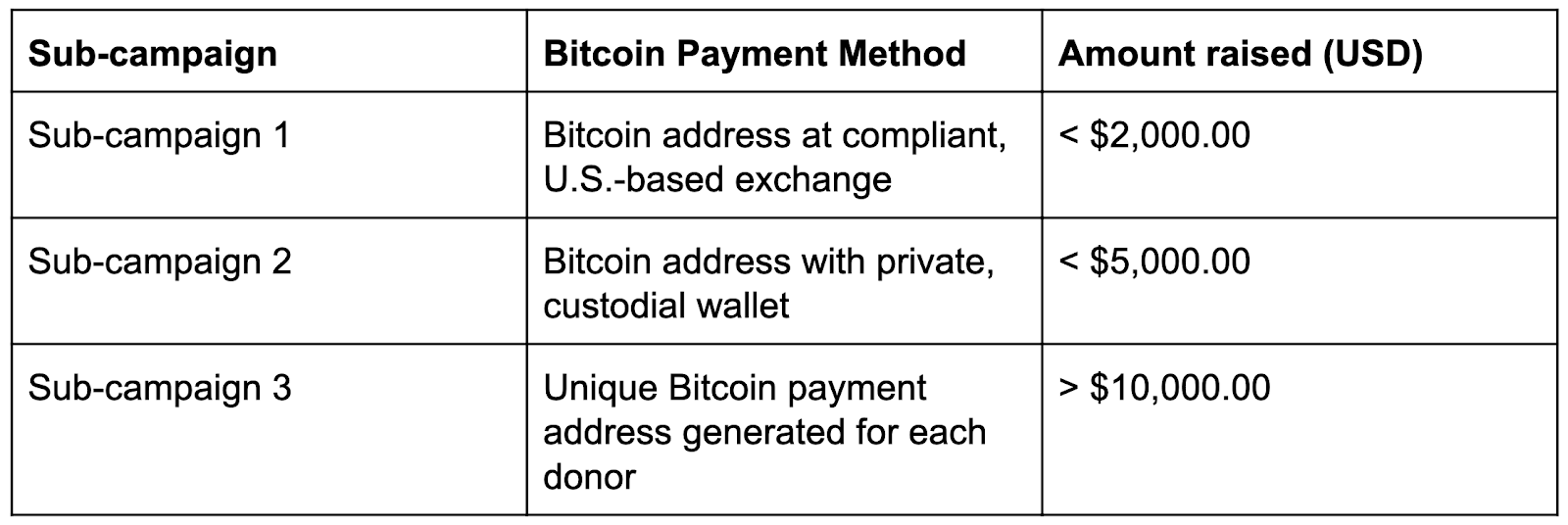

The easiest way to understand the evolution of AQB’s 2019 campaign is to divide it into three sub-campaigns, based on the type of wallet the organization used to receive donations.

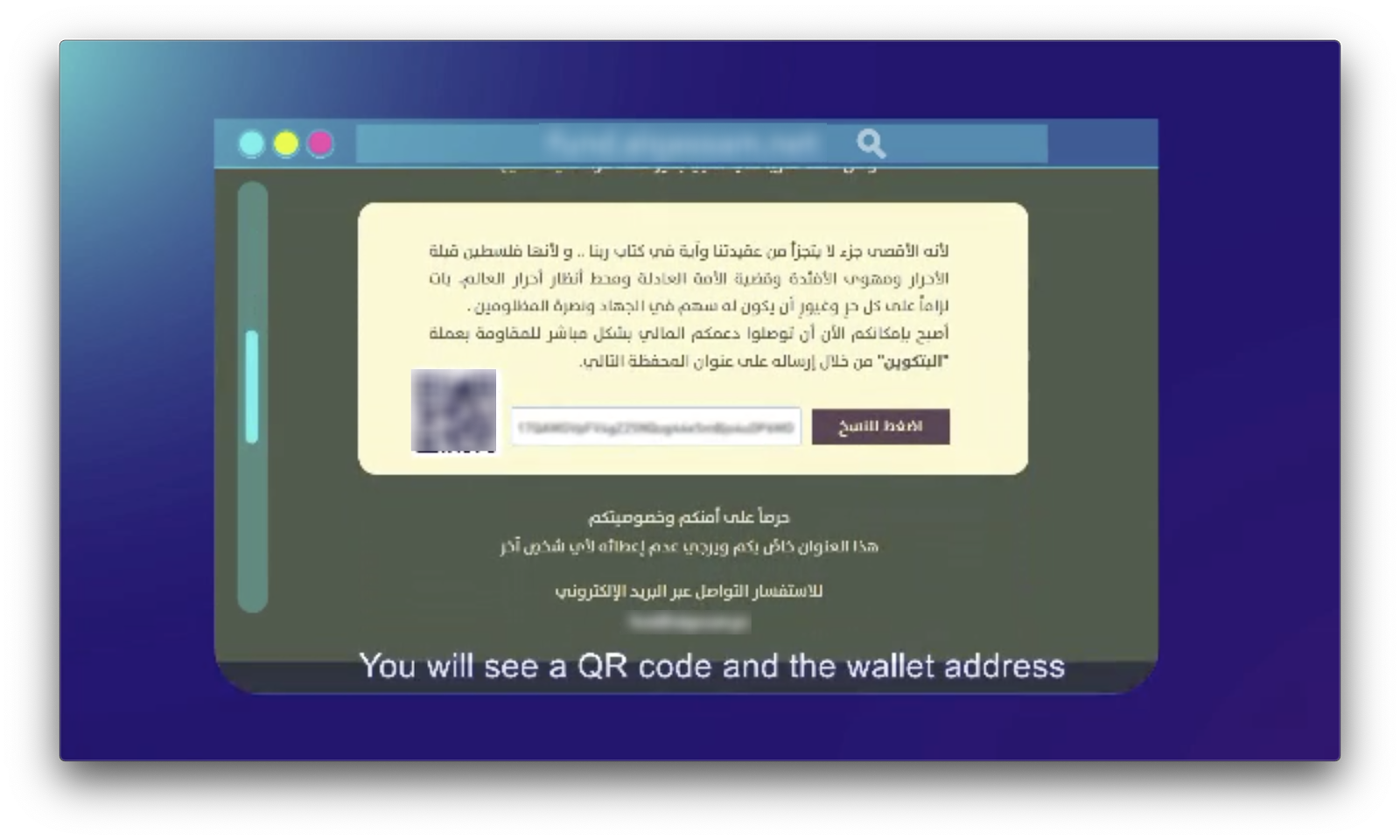

The first sub-campaign began in January of 2019, when the AQB website began displaying a message inviting users to “donate to the jihad” with a QR code underneath leading to a single Bitcoin address.

That Bitcoin address was associated with an account at a U.S.-based, regulated exchange. Law enforcement was quickly able to alert the exchange, have the account frozen, and investigate the individual who established it at the exchange, as well as transactions that contributed to that account.

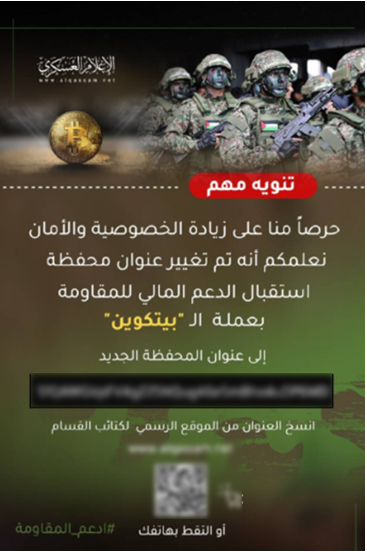

The second sub-campaign began when AQB replaced the exchange address with a new one linked to a private, non-custodial wallet, citing the need for increased anonymity. Nonetheless, cryptocurrency analysts were still able to trace donations to and withdrawals from the address with the help of Chainalysis.

Soon after that, however, AQB launched the much more advanced third sub-campaign, with a Bitcoin wallet integrated into their website that generated a unique Bitcoin address for each donor to which they could send contributions. AQB also published a video on its website telling users exactly how to donate as anonymously as possible.

AQB’s instructional video provided two methods for donors to send in Bitcoin. In the first method, donors were instructed to go to a hawala, a type of money service business that’s popular in the Middle East. Donors could simply go to a hawala, hand over however much cash they wished to donate, and provide the donation address AQB gave them. From there, the hawala would send the equivalent amount of Bitcoin.

For the second method, donors were instructed on how to create their own private wallet from which they could send their donation — AQB’s video even displays a list of recommended wallets and also exchanges where they can get Bitcoin. AQB’s instructions were quite thorough, even telling donors to use public wifi when creating their private wallet to avoid compromising their IP address. Overall, Sub-campaign 3 is the most advanced usage of cryptocurrency technology we’ve observed in a terrorism financing campaign.

Analyzing AQB’s donations

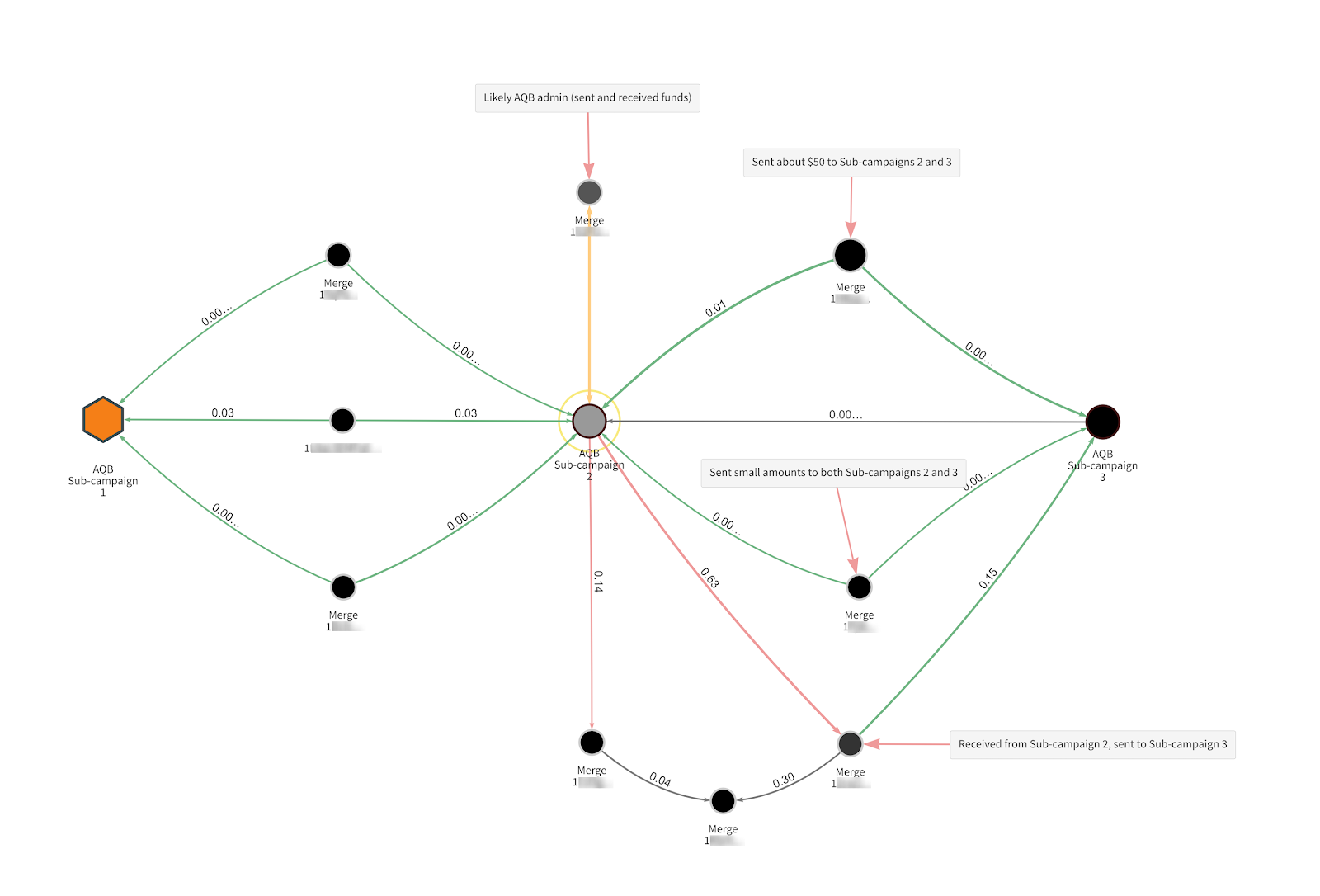

Looking at all three sub-campaigns in Chainalysis Reactor, we see that some donors contributed Bitcoin to multiple AQB campaigns. However, we’ll focus most of our analysis on Sub-campaigns 2 and 3, as they attracted most of the donations and the latter of the two is still collecting funds.

The fact that the Al Qassam Brigades’ website-based wallet generates a new unique address for each donor makes it more difficult to identify addresses associated with Sub-campaign 3 and track transactions in and out of those addresses. Under normal circumstances in a scenario like this, we would possibly send a small amount of cryptocurrency to help us learn more about the address. But that option was off the table here, as it’s illegal to transact with an address belonging to a designated terror organization. However, using court documents from associated cases and analysis of transactions from the first two sub-campaigns, we were able to discover addresses that received donations as part of the third sub-campaign. We then used Chainalysis Reactor to find many more addresses. As of December 27, 2020 we’ve identified over 100 addresses that received Bitcoin donations during Sub-campaign 3. Below is some of the data we’ve aggregated from analyzing donations to those addresses, as well as the address associated with Sub-campaign 2.

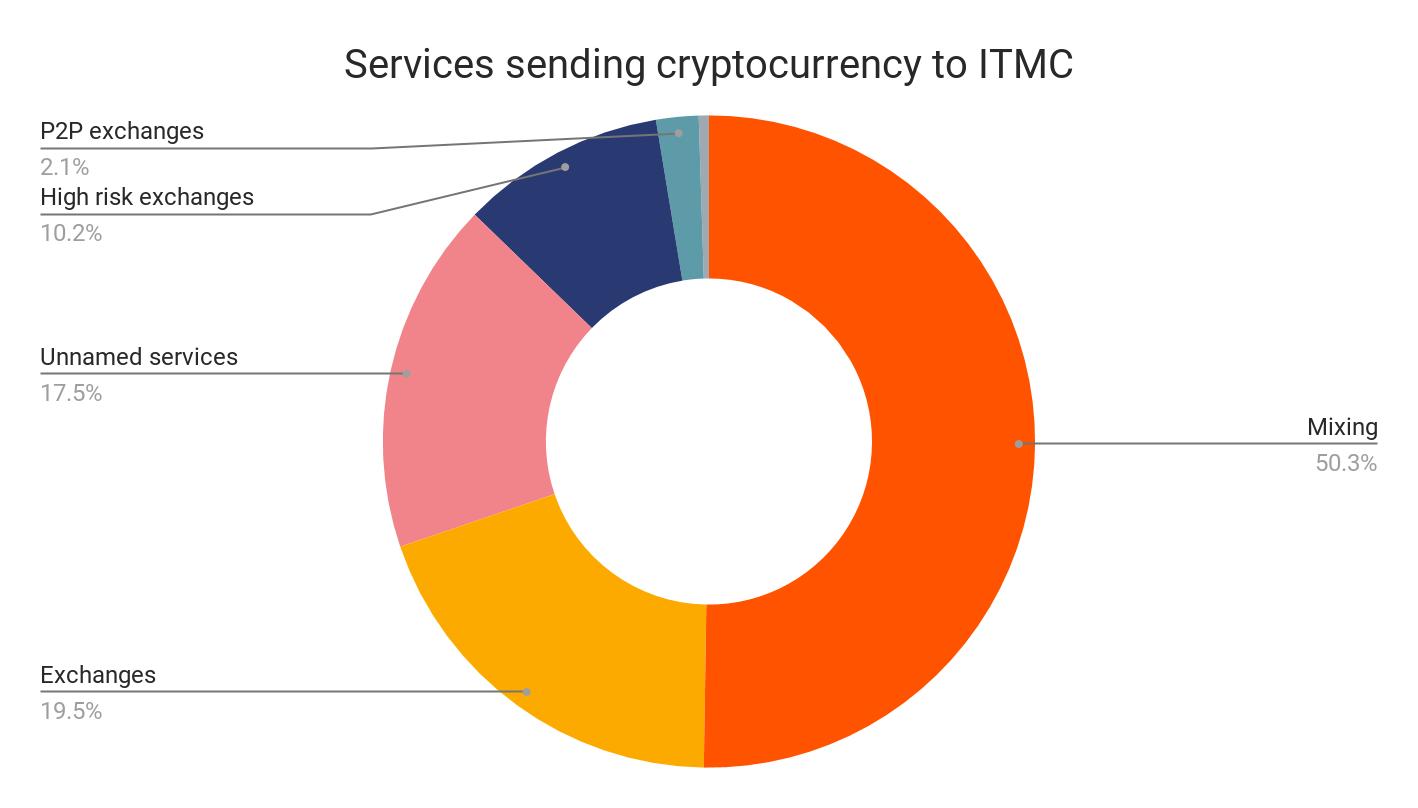

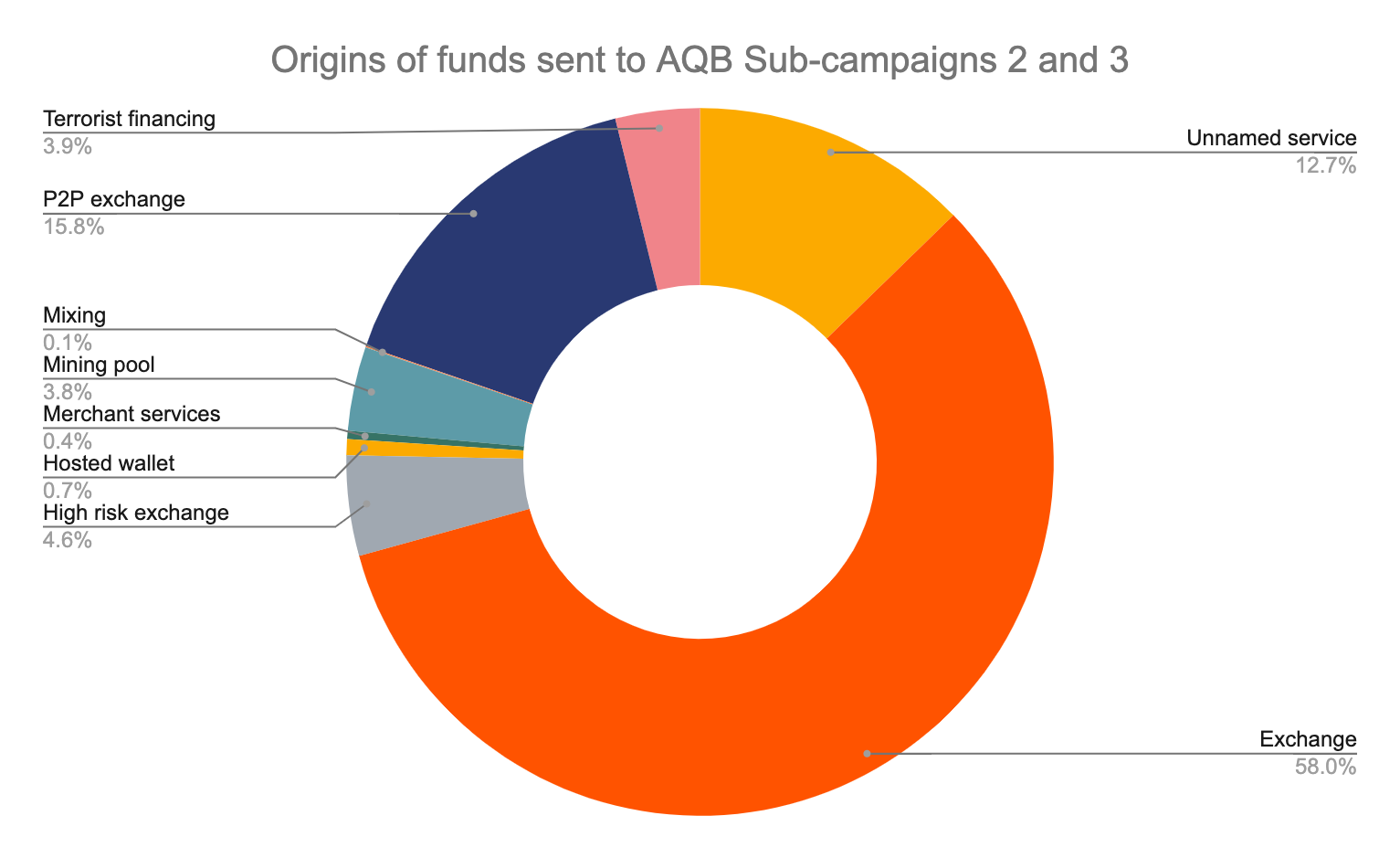

Overall, the largest share of AQB’s donations to Sub-campaigns 2 and 3 came from standard exchanges that collect KYC information from users. However, a substantial amount also came from high-risk exchanges, P2P exchanges, and other addresses associated with terror fundraising. Interestingly, AQB received no funds from mixers, which is where the bulk of ITMC’s donations came from during its 2016 to 2018 campaign. One possible explanation is that ITMC’s supporters are more knowledgeable of cryptocurrency and therefore know that a mixer can help obscure the path of their donations, but we have no way of verifying this. It’s also possible that AQB’s donors didn’t use mixers because doing so wasn’t included in the instructional video promoting the campaign, or because they thought the unique address generation component of Sub-campaign 3 ensured sufficient anonymity.

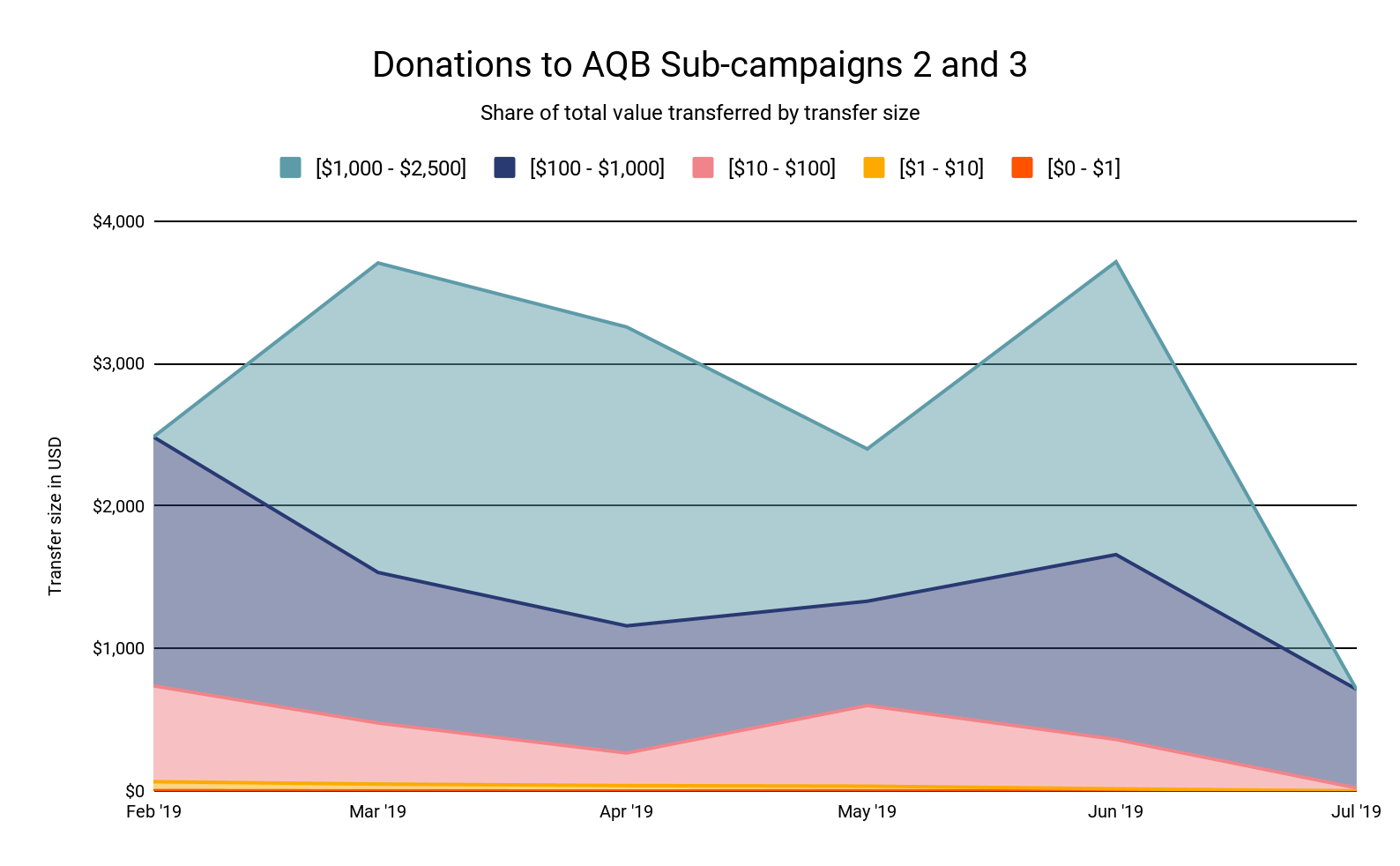

Across more than 100 donations, we found that the median amount sent was just $24, though the average was much higher due to a few large outliers. The highest amount sent in a single donation was $2154 — besides that, there were only two other donations above $1000. 13% of all donations were between $100 and $1000, 10% were between $50 and $100, and 75% were below $50.

While most donors gave relatively small amounts, there were still enough large donors for Sub-campaign 3 to bring in tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of cryptocurrency for AQB. Given the success of AQB’s donation campaign, we may see other terrorist organizations launch similar campaigns to this one in 2020 and beyond. We hope that by continuing to analyze these transactions, we can not only enable investigators to identify the donors and financial facilitators administering AQB’s campaign, but also continue learning more about the changing tactics of terrorism financing in cryptocurrency.

What do these campaigns tell us about terrorism financing in 2020?

Comparing donations for ITMC and AQB terror campaigns

Across its three sub-campaigns, AQB raised roughly the same amount in cryptocurrency during its 2019 fundraising push as ITMC did during its campaign that ended the previous year. AQB also attracted more individual donors. This is more concerning when you consider the fact that AQB’s campaign has been active for just nine months, compared to two years for ITMC. The comparison suggests that terrorist groups could be improving their ability to attract donors online.

But what stands out most when comparing the two campaigns is how much more sophisticated AQB’s address generation infrastructure is, as it presents a significant challenge to investigators tracing donations. It’s possible that in 2020 and beyond, more terrorist organizations will embrace cryptocurrency as a fundraising tool and push for further advancements that allow them to take in more funds and enhance their privacy.

Terrorist groups have proven adept at leveraging emerging technologies to advance their agenda, with groups like ISIS’ mastery of social media being a prime example. The last thing we want is for cryptocurrency to become another tool at their disposal. Law enforcement, intelligence agents, and the cryptocurrency community as a whole must remain vigilant to ensure this doesn’t happen.

This blog is an excerpt from the Chainalysis 2020 Crypto Crime Report. Click here to download the full document!