Extremism, in its many forms, represents an ongoing threat to global peace and security. Often fueled by ideological grievances and disinformation, these movements exploit the financial system — including through cryptocurrency — to disseminate propaganda through their own media platforms, garner support for their causes, and carry out attacks.

Regulators and law enforcement in many jurisdictions are increasingly turning their attention towards groups that fall outside the traditional definitions of terrorism, but still pose risks due to their transnational influence and reach. Unlike internationally recognized terrorist organizations like the Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham (ISIS) or Boko Haram, which are defined by direct acts of violence and meet explicit government-defined criteria, many groups espousing extremist ideology advance their agendas without directly engaging in violence themselves. However, such groups often incubate and promote escalation to violence, making it critical to understand and disrupt their financial lifelines.

To that end, recent international actions demonstrate a growing effort to disrupt the financial activities of groups that operate in the grey areas of traditional counterterrorism frameworks. For instance, the United States (U.S.) Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned the Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM), while the U.S. Department of State designated the white supremacist group The Terrorgram Collective and three of its leaders. These measures form a broader strategy to address the threat posed by racially or ethnically motivated violent extremism (REMVE) and the transnational threat of violent white supremacism. Similarly, the European Union (EU) sanctioned The Base, a neo-Nazi accelerationist group also designated as a terrorist organization by Australia, Canada, and other jurisdictions.

This section explores cryptocurrency flows to groups across the political and ideological spectrum, including groups that would be considered far-right and far-left in traditional parlance. We examine the ideologies driving their activities, donor patterns, and regional and cross-ideological dynamics. Although cryptocurrency contributions to these causes remain relatively small, any amount directed toward extremist ideologies can have an outsized impact and warrants deeper scrutiny. By analyzing these networks, we aim to provide insights into how these groups operate and identify emerging threats that extend beyond the conventional understanding of terrorism.

A note on methodology

The analysis in this section draws on multiple sources, including public sanctions lists and research from organizations specializing in extremism and terrorism financing. We categorize groups based on their stated ideologies, documented activities, and identifiable links to extremist behavior.

Through blockchain analysis, we investigate known wallet addresses associated with these organizations to uncover patterns of financial support, regional dynamics, ideological crossovers, and on-chain behavioral trends of donors and recipients. These insights provide a clearer picture of how these groups are leveraging cryptocurrency to sustain their operations.

We contextualize these findings within the broader landscape of increased regulatory scrutiny on extremist financing and risk-based debanking1. By examining the typologies of groups across the gamut of extremism, we seek to deepen the analytic and policy community’s understanding of their funding mechanisms.

While this analysis sheds light on certain on-chain activities, it is impossible to capture the full scope of financing, as much likely occurs off-chain through traditional banking and informal systems, as well as content monetization and crowdfunding platforms.

A note on terminology

In this report, we use the term “extremist group” or “extremist financing” to describe organizations or financial activities involving groups across the political and ideological gamut that may still not meet the criteria for designation as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) in the United States. While FTOs are formally recognized entities based on specific government-defined criteria, the groups referenced here may engage in a broader range of activities that do not explicitly involve terrorist acts, but still contribute to the incubation or spread of radical ideologies that often defend or legitimize political violence. This includes groups that fall under the umbrella of REMVE — promoting ideologies grounded in racial or ethnic hatred. A broader lens is essential for understanding how such groups fund themselves, as their activities may eventually lead to violent outcomes. By addressing the full scope of extremist financing, we aim to surface proactive strategies to mitigate risks.

The term “extremist financing” is similarly broader in scope than the legal definitions of terrorism financing found in international frameworks, such as those of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Generally, terrorism financing is defined as the collection or provision of funds with the intent or knowledge that they will be used to carry out acts of terrorism. By contrast, extremist financing in this report includes financial flows that support groups engaging in ideological or political activities that promote or reinforce professed hatred of a group of people, even in the absence of direct violence.

Trends in crypto contributions to extremist groups decline overall, but show concerning traction in Europe

Groups espousing extremist ideology have increasingly turned to cryptocurrency as a means of securing financial support, particularly after being excluded from traditional financial institutions (FIs). Many of these groups have faced debanking, forcing them to seek alternative methods of funding. For example, one U.S.-based white supremacist group explicitly cited their loss of access to traditional payment rails, redirecting donors to cryptocurrency.

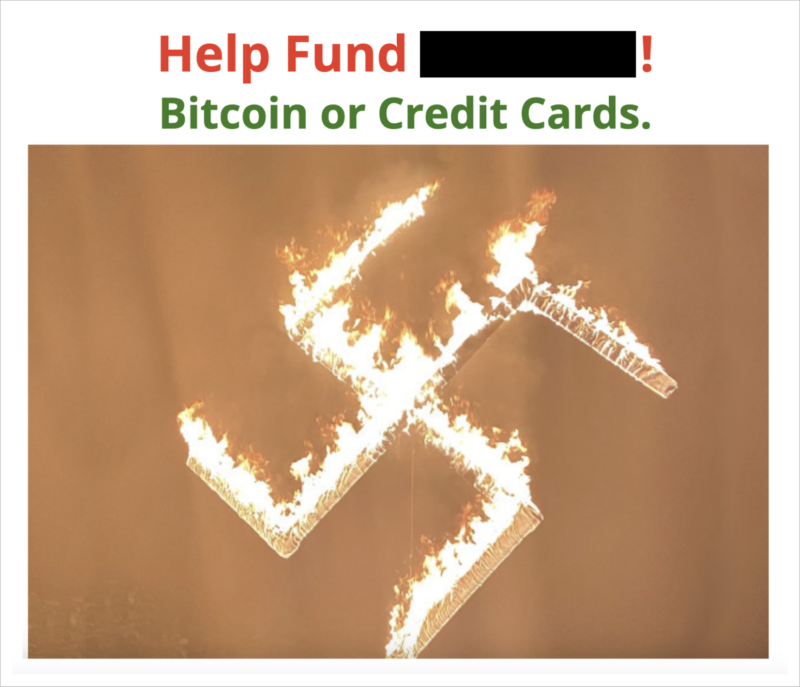

The transition to crypto proved effective for this particular group, netting them roughly $40,000 worth of cryptocurrency since publishing a donation address. The shift from traditional banking to cryptocurrency represents a broader trend among ideological groups seeking to maintain their financial lifelines. As shown below, one group solicits donations via bitcoin and credit card, while leveraging a burning swastika to promote their cause.

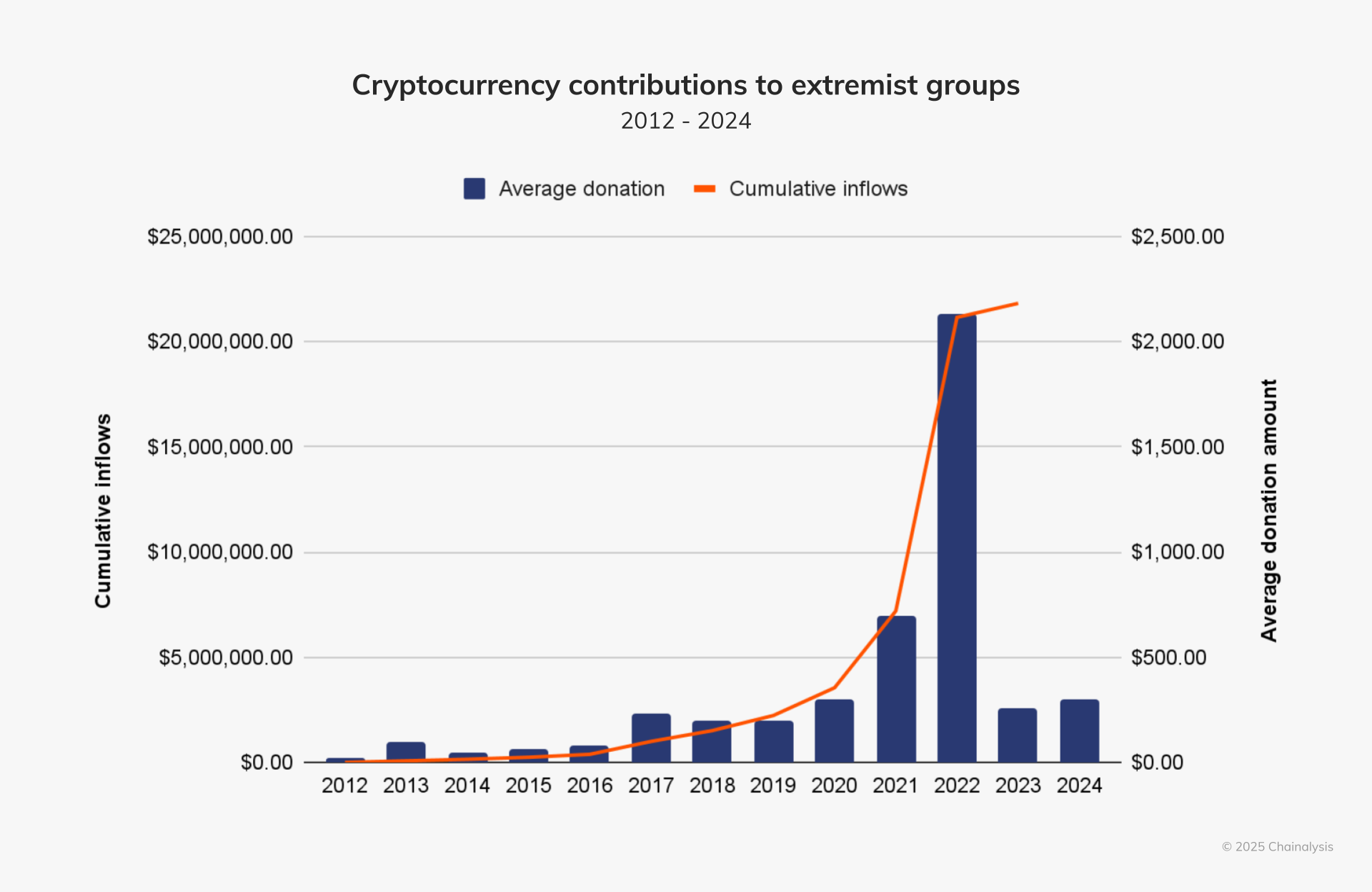

The chart below shows an upward trend since 2012 in cumulative flows to ideological groups worldwide.

Despite the cumulative growth in contributions, the average payment size generally has remained in the hundreds of dollars each year (with the exception of 2022). This suggests that grassroots campaigns, consisting of small contributions from individual donors, continue to drive cryptocurrency funding for ideological groups.

However, there was a notable increase in cumulative contributions and average payment amount during the COVID-19 pandemic era, circa 2020-2022 — a time marked by heightened ideological divisions and the rapid spread of misinformation. This growth reflects an expansion in both the number of donors and the size of individual contributions.

The spike in average annual deposit amount in 2022 is anomalous. That year, the far-right conspiracy theory and disinformation platform InfoWars received an $8 million contribution from a single donor. This coincided with a series of legal losses related to the Sandy Hook defamation case, significantly skewing the data for that year. This speaks to how specific events can act as flashpoints for increased donations — a dynamic we will explore in greater detail later on.

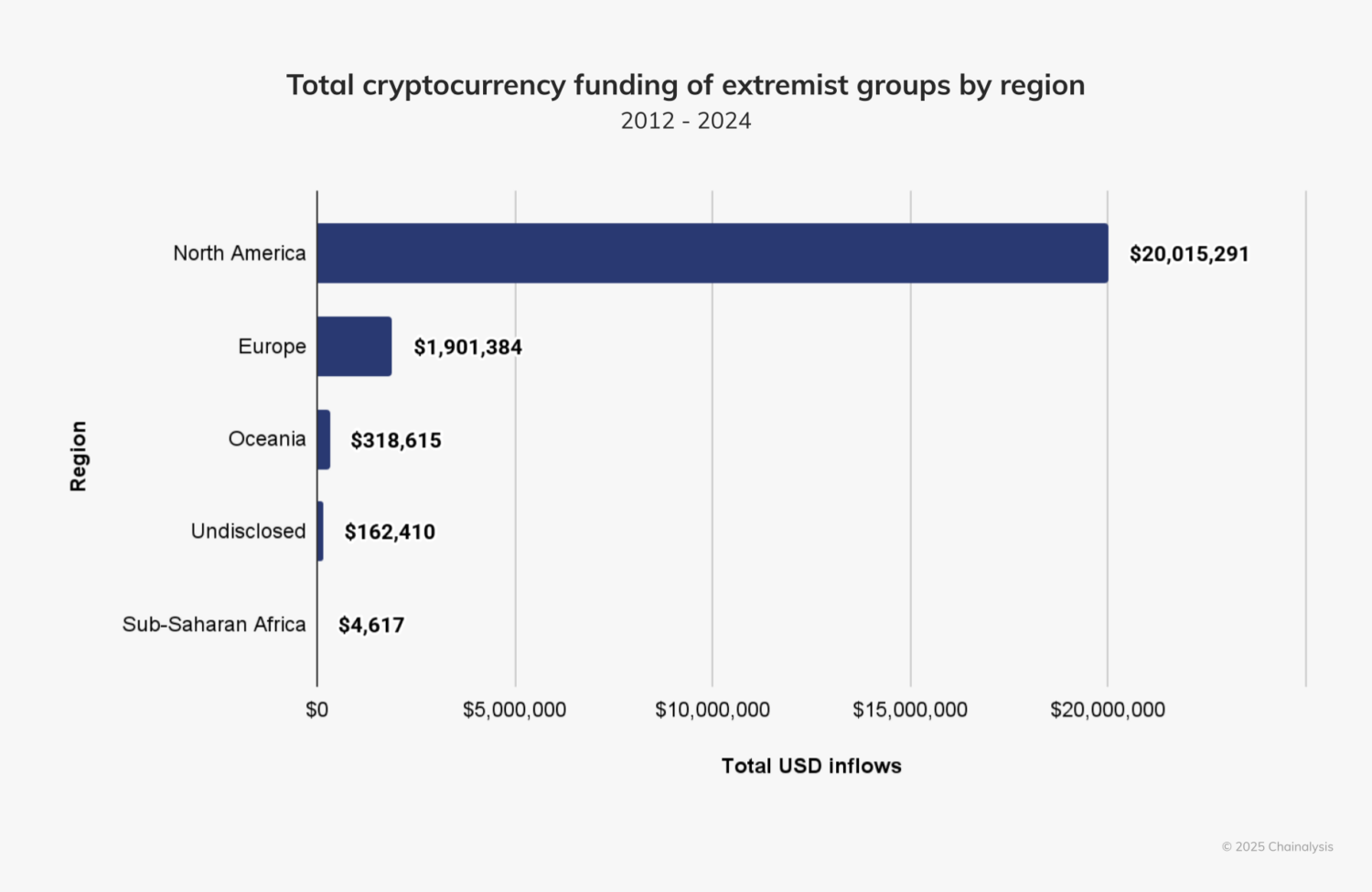

North America is number one for extremist financing, but Europe is the fastest growing region

The intersection between regional and ideological dynamics presents a complex picture. While overall observable crypto funding is somewhat stagnating overall year-over-year (YoY), certain ideologies in specific regions are experiencing significant YoY growth. This suggests localized surges in support for particular causes, driven by political, social, or cultural factors that resonate strongly in those regions.

North America is the global leader in extremist funding via cryptocurrency, with over $20 million in total contributions, far surpassing other regions.

This dominance likely reflects the presence of prominent groups and platforms like The Daily Stormer and InfoWars in the U.S, which serve as hubs for both domestic and international activity. Debanking efforts in the United States targeting both far-right and left-leaning groups may have driven many to cryptocurrency as an alternative financial system.

With $318,615 in inflows, Oceania, reflecting contributions in Australia and New Zealand, stands out relative to its small population and fewer extremist organizations. The Christchurch mosque attacks in 2019, which cost approximately NZ $60,000 (roughly $33,567 USD) to execute according to estimates by the New Zealand Police, underscore that extremist groups can achieve devastating impact without vast sums.

Europe’s share of cryptocurrency inflows to extremist groups is on the rise

Until 2017, North America accounted for virtually all on-chain flows to extremist groups, reflecting earlier adoption of cryptocurrency. Beginning in 2017, Europe began to capture a noticeable share of these inflows, as we see below, and its share has grown steadily since.

Between 2022 and 2024, Europe’s share rose dramatically, commanding as much as nearly 50% of total inflows.

This growth is likely driven by rising white supremacist, nationalist, anti-Semitic and Holocaust denial narratives, as well as “remigration”-focused organizations that advocate for reversing migration trends. These groups have successfully used divisive narratives to attract funding in increasingly polarized political climates.

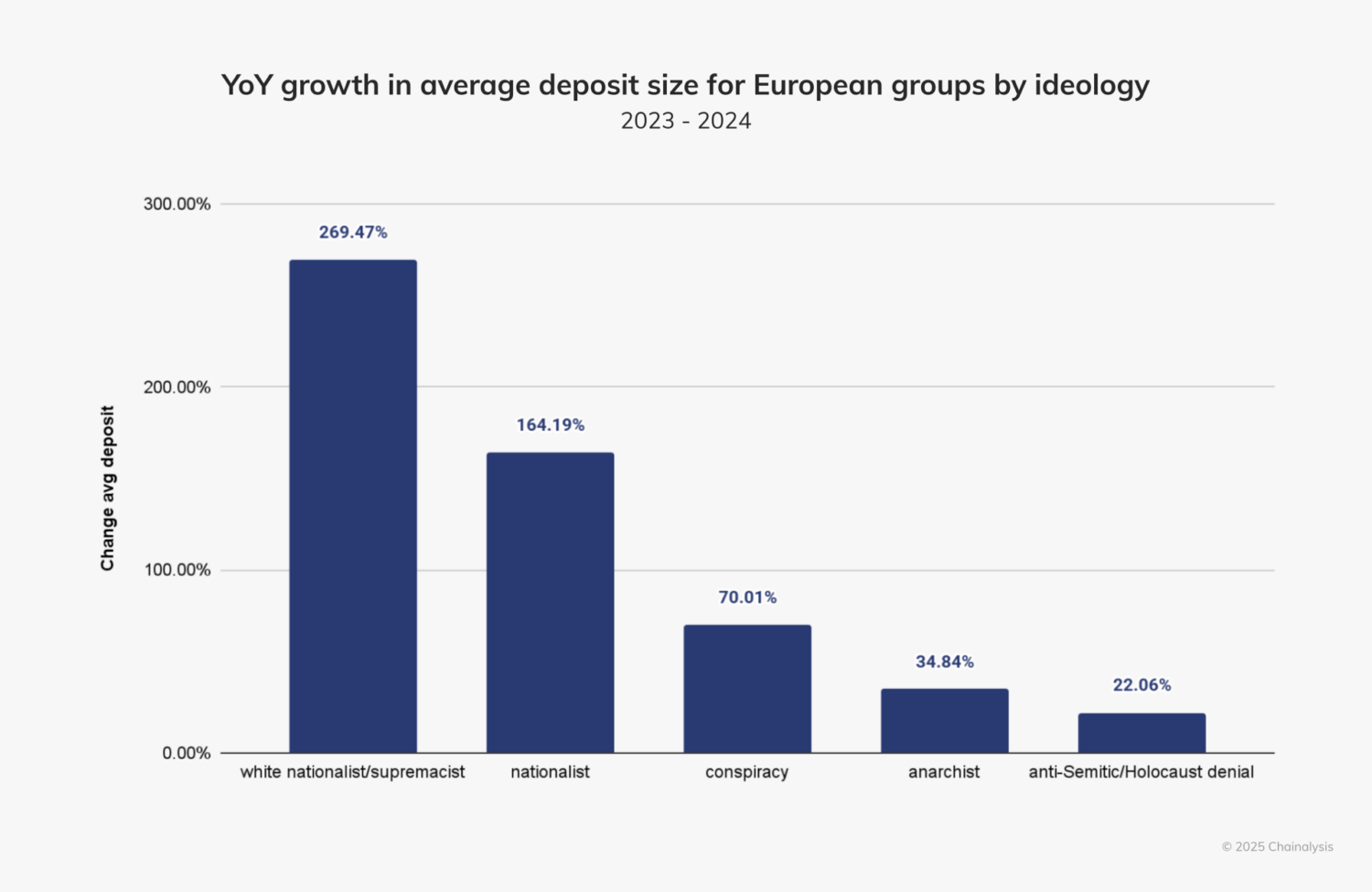

Europe also witnessing increased donor intensity

In addition to growth in overall inflow share, some ideologies are experiencing marked increases in average deposit size, reflecting a rise in the intensity of donor support. The chart below shows the top five ideologies in Europe by growth in average deposit size.

White nationalist and nationalist groups lead, with conspiracy, anarchist, and anti-Semitic/Holocaust denial groups also showing marked growth, suggesting European groups have successfully leveraged these narratives to mobilize financial support.

This is particularly striking in the context of stricter regulations and outright bans on hate speech, Nazi symbols, and Holocaust denial in countries like Germany, Austria, and the Baltic states. Furthermore, many European countries limit open solicitation of funds, pushing some extremist groups toward more covert fundraising methods to avoid scrutiny, such as through privacy coins — an issue we will explore later on. This makes it likely that the true scale of ideological support is even greater.

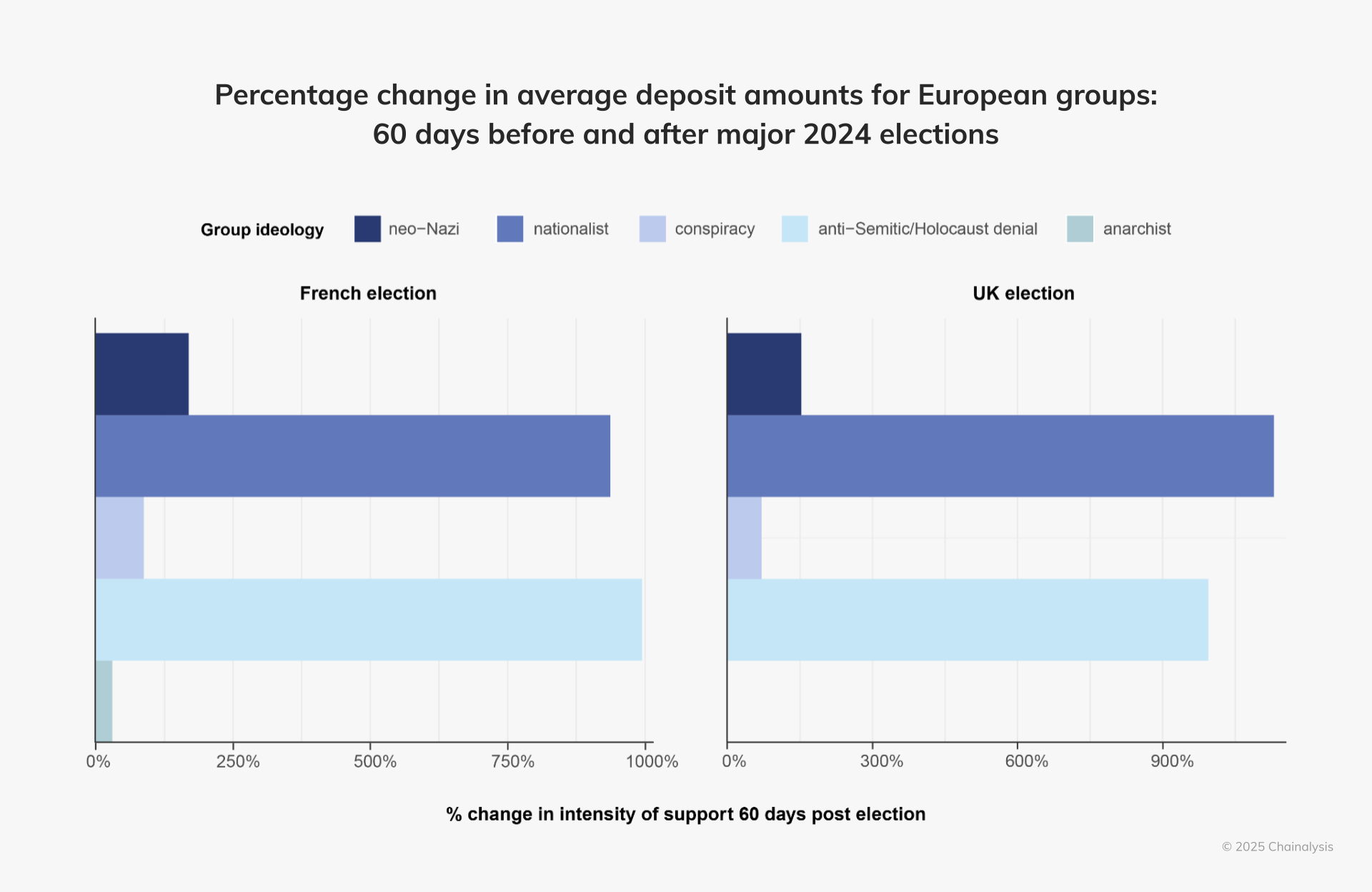

Highly polarized political events, such as national elections, often catalyze surges in donation and donation amounts. Major European election events prompted significant increases in average deposit sizes, reflecting the donor enthusiasm and strategic leveraging of political moments by ideological groups.

Donations surge in Europe around major political events

The chart below shows how average deposit sizes surged across select ideological categories in response to major 2024 European elections, illustrating the connection between on-chain financial activity and off-chain political developments. Changes in average deposit size are an indicator of the intensity of donor support, which can provide a more nuanced view than total donation volume alone.

Significant increases in donation amounts were observed around elections in France and the United Kingdom (UK). Nationalist and anti-Semitic groups in particular, as well as neo-Nazi and conspiracy-oriented groups benefited from these moments, increasing their backing. While some of this growth may be part of longer-term cyclical trends, these spikes reflect how elections can act as flashpoints for extremist fundraising, driving greater financial contributions from ideologically aligned donors.

Many of these surges appear linked to event-specific campaigns. For example, targeted fundraising around near-wins or setbacks for ideologically aligned candidates often prompt increases in the intensity of support. Election outcomes also drive donor enthusiasm, with spikes post-election likely reflecting either celebration of favorable results or urgency following perceived losses.

How extremist groups leverage ideological overlaps to strengthen networks and amplify resources

A concerning trend among ideological groups is the deliberate blending of ideologies to broaden appeal. For example, movements might combine homophobic rhetoric with white supremacist or pro-Russia themes, strategically attracting wider audiences by capitalizing on overlapping grievances and similar narratives.

The imagery below — sourced from a content platform promoting anti-Semitic, homophobic, pro-Russia content and conspiracy theories — illustrates how groups strategically overlay hateful ideologies.

Casting a wide net, these groups unite seemingly unrelated grievances by rallying around a common enemy or shared cause.

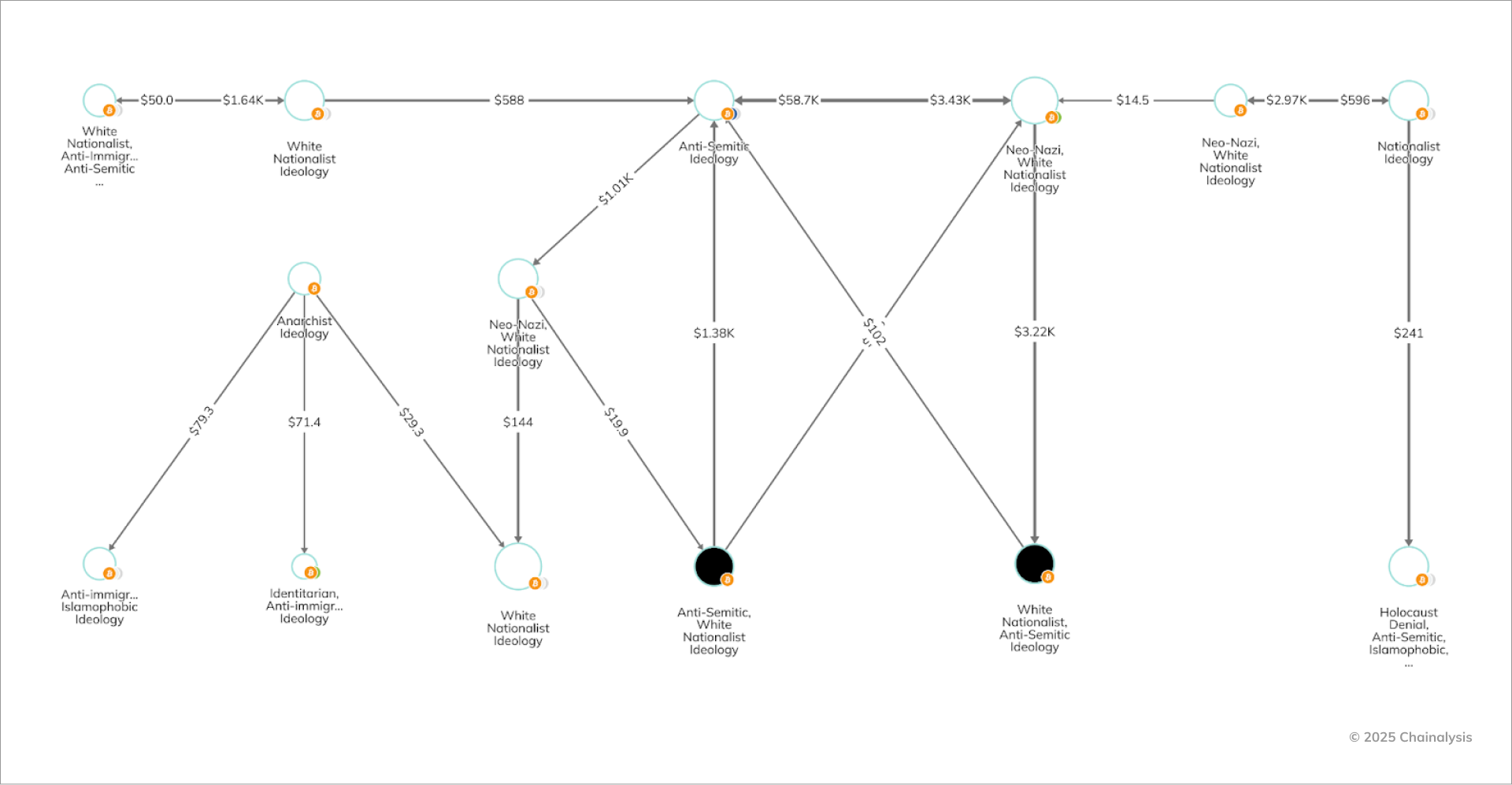

In addition to ideological crosspollination, on-chain transactions reveal further evidence of pan-ideological alignment. Understanding these connections through blockchain analysis not only reveals how these groups align ideologically, but also refines our understanding of their relationships, financial behaviors, and operational strategies. For example, white nationalist organizations have shown a propensity to donate to other extremist organizations, suggesting collaboration and shared goals that cross ideological boundaries.

The Reactor graph below reveals cryptocurrency contributions from white nationalist groups to a variety of organizations promoting ideologies such as Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, and Holocaust denial.

Financial interconnectedness further strengthens their networks and sustains their operations, amplifying collective influence. Additionally, on-chain interactions also reveal how these groups identify allies both ideologically and financially.

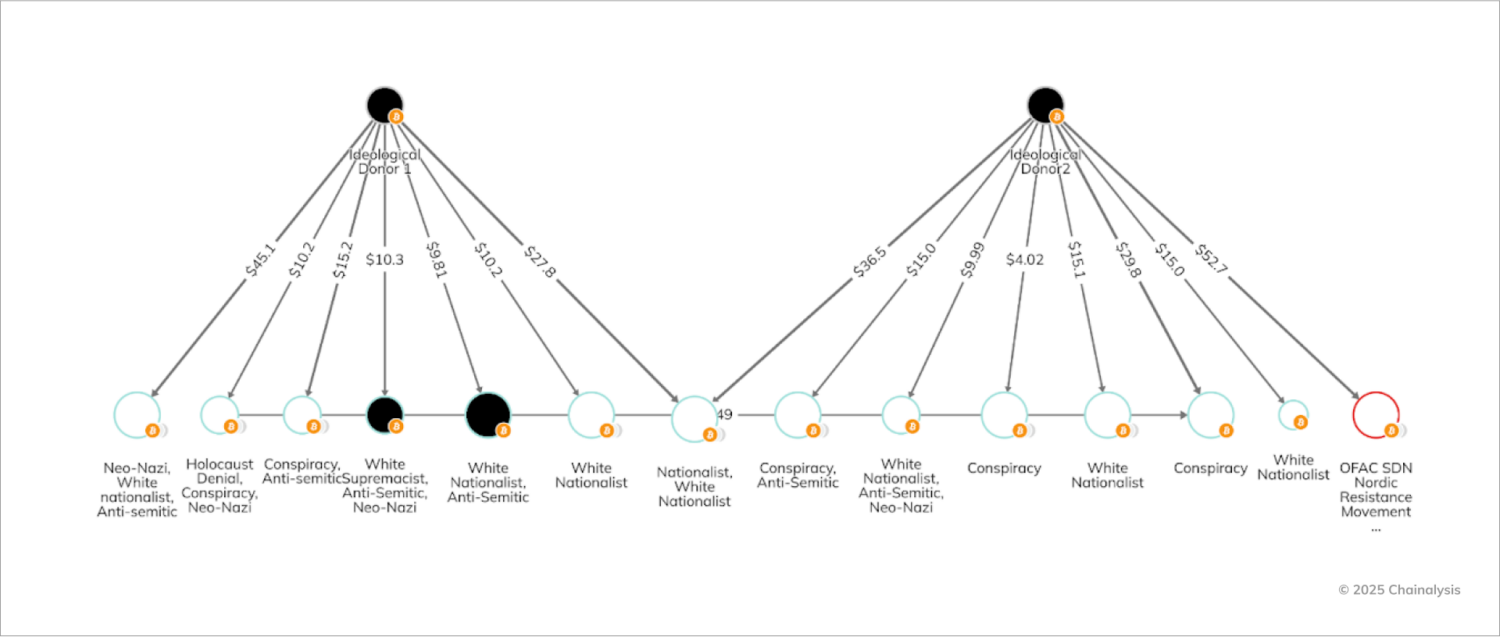

Additionally, we have observed that individual donors — who collectively have the most impact on overall extremism funding through cryptocurrency — frequently support multiple causes. In the Reactor graph below, we see two donors contributing to a range of campaigns.

The ability to visualize the on-chain footprint of a neo-Nazi, Holocaust-denying, white nationalist donor alongside the financial behavior of their broader network, is an invaluable tool. Blockchain analysis provides a broader understanding of the entire ecosystem, going beyond isolated incidents to reveal connections between entities and uncovering insights that are often inaccessible through traditional financial rails, especially for private sector partners. It enables proactive, continuous monitoring of evolving tactics as groups adapt to new challenges, and reveals the links between ideological groups and the behavior of donors who contribute to their activities.

How ideological groups are leveraging privacy measures to evade detection

Many groups are increasingly concerned about being targeted, particularly those that have already been debanked or have faced financial restrictions due to their activities.

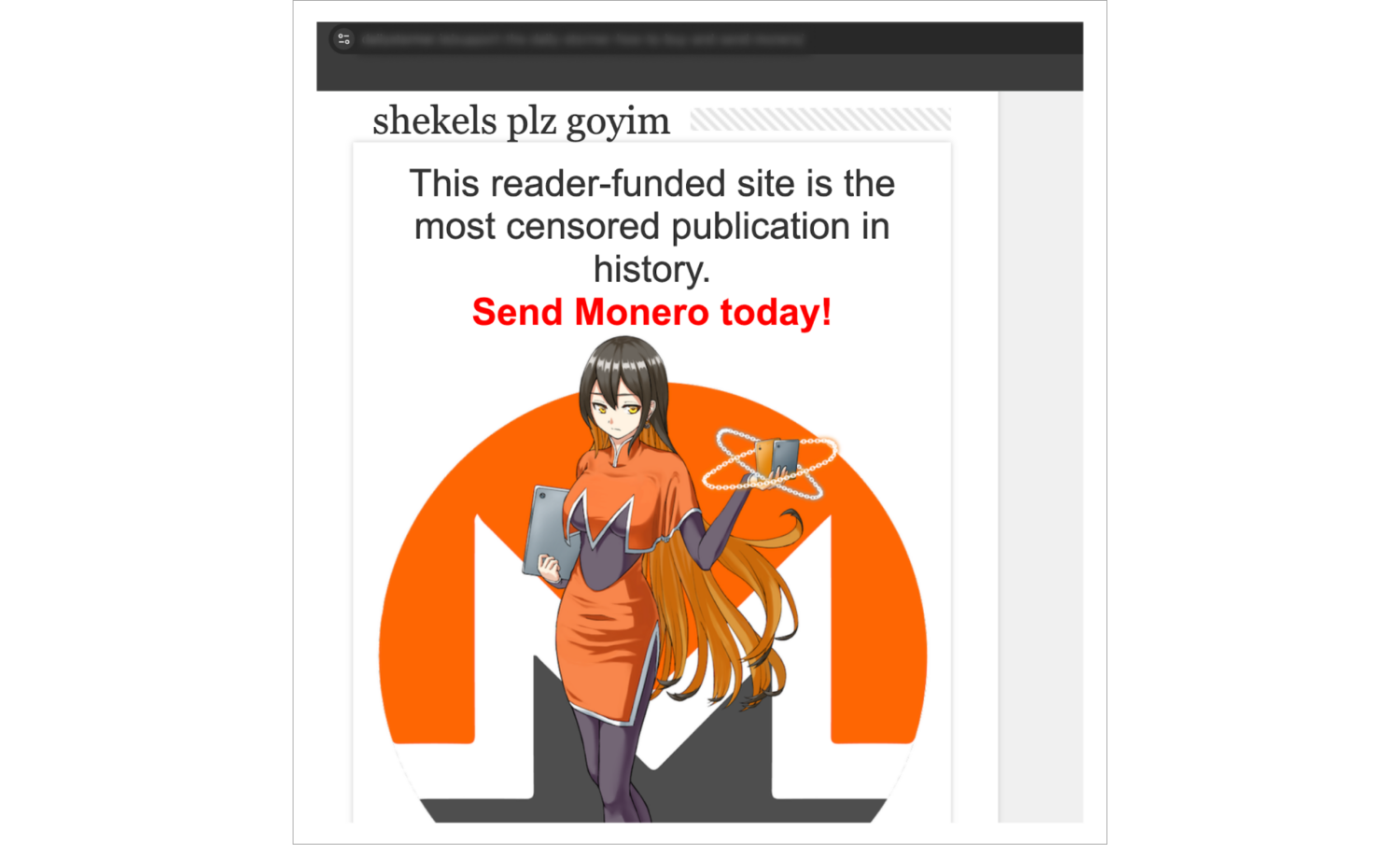

For example, the neo-Nazi and white supremacist website The Daily Stormer, has faced significant backlash for its role in inciting violence and promoting hate speech. The site gained widespread notoriety after publishing content glorifying violence and racism, including during and after the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia that turned deadly. The nature of its content led multiple hosting providers to revoke its web domain. Despite deplatforming, the website moved to the darknet to circumvent these restrictions and continues to maintain operations and fundraise via the privacy coin Monero, as seen below.

Some groups have stopped publicizing cryptocurrency donation addresses altogether, opting instead to share donation details privately or exclusively through direct communication. These adaptations reflect efforts to evade detection while maintaining funding streams.

Although these groups are not yet highly sophisticated in using advanced tools such as mixers, bridges, or decentralized exchanges (DEXs), their growing reliance on privacy-focused cryptocurrencies reflects a growing awareness of the stakes of transparency in traditional blockchain networks and a desire to preserve their operational anonymity.

Challenges and opportunities in managing extremist financing risks

Groups espousing extremist ideology, particularly those operating across multi-ideological networks, present challenges for monitoring and regulation. One of the most fundamental obstacles lies in the inconsistency or outright absence of a clear legal framework addressing extremism across jurisdictions. Unlike FTOs, many groups fall into a grey area, making it challenging to identify them under the existing anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) frameworks. This lack of consensus further complicates enforcement efforts, as regulatory obligations for monitoring or blocking transactions involving these groups are not always well defined.

Extremist groups thrive in legal grey area created by jurisdictional inconsistencies

Extremist groups often occupy a legal grey area, depending on the country, complicating global efforts to track, report, and disrupt financial flows associated with them. For example, a neo-Nazi group in the U.S may be legally allowed to operate and fundraise under free speech protections, while similar groups in countries like Germany are banned outright. In some cases, removing such groups from platforms could be considered debanking, which raises political and ethical debates about free speech and financial access, as seen in ongoing discussions in the U.S. But in countries with stricter anti-extremism laws, not only are such groups denied access to bank services, they could also face criminal prosecution. This inconsistency extends to centralized exchanges (CEXs) — the primary cash-out points to convert cryptocurrency to fiat currency — which operate under varying AML/CFT standards. While many enforce strict Know-Your-Customer (KYC) measures, others operate under looser regulations, creating gaps that extremist groups may use to their advantage. The unclear legal status of many such groups further complicates whether exchanges are legally obligated to block transactions or file suspicious activity reports (SARs) related to these actors.

Complex categorization of actors

Determining whether a group fits into a banned category often requires deep analysis of specific country regulations. Ideologically extreme groups that blend legal and illegal activities can evade clear categorization, which complicates monitoring efforts. Without specific groups being blacklisted or sanctioned, the approach to identifying and taking action against such groups may vary drastically depending on jurisdiction.

Blockchain analysis enhances awareness of extremist activity on-chain

While the overall amount raised through cryptocurrency by ideologically extreme groups is relatively small, any amount is concerning given the potential activities it could support. Even modest amounts of funding can finance propaganda, recruitment, or violence — making proactive oversight essential. Blockchain analysis provides critical insights about the financial activity of such groups that would otherwise be difficult to uncover.

While global regulation on extremism remains inconsistent, the insights offered by Chainalysis can support efforts to establish monitoring practices across jurisdictions. By shedding light on how these groups leverage cryptocurrency, Chainalysis equips both the public and private sectors with the tools needed to better mitigate risks.

Endnotes

[1] Debanking or de-risking refers to the practice of financial institutions (FIs) restricting accounts or denying banking services due to perceived risks associated with the account holder’s activities. This has raised debates, including in the U.S., about financial inclusion and whether some groups are being unfairly excluded from banking services.

[2] Undisclosed may refer to groups or organizations that either do not publicly reveal their location of operation or operate in a manner that obscures their geographic presence.

[3] It’s important to note that many groups in our sample are now inactive, while others have shifted their strategies by using alternative content monetization platforms or transitioning to privacy coins for greater anonymity. This report does not include analysis of transactions in privacy coins in totals.

[4] While marginally distinct, groups that espouse white nationalist and white supremacist views, as well as anti-Semitic and Holocaust denial views have been bucketed together respectively due to significant ideological overlap. White supremacists advocate for the inherent superiority of white people and racial hierarchies, while white nationalists seek to establish or preserve a white ethnostate, ultimately rooted in white supremacist ideals. Holocaust denial is a specific form of anti-Semitism that rejects or distorts facts about the Holocaust to delegitimize Jewish suffering and propagate anti-Jewish sentiment.

This website contains links to third-party sites that are not under the control of Chainalysis, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Chainalysis”). Access to such information does not imply association with, endorsement of, approval of, or recommendation by Chainalysis of the site or its operators, and Chainalysis is not responsible for the products, services, or other content hosted therein.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.