This blog is a preview of our 2021 Geography of Cryptocurrency report. Sign up here to download the whole thing!

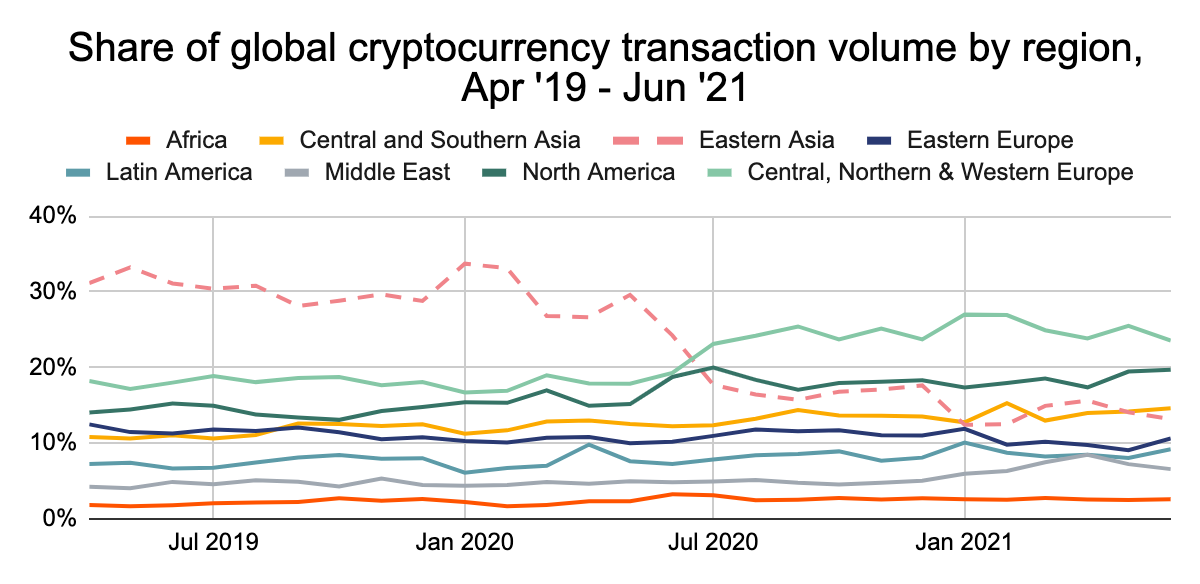

Eastern Asia is the third-largest cryptocurrency market we study, having received $590.9 billion worth of cryptocurrency between July 2020 and June 2021, which represents 14% of all activity during that time period. The region’s overall transaction value grew 452% compared to the previous year, which makes it the slowest-growing region we study. Eastern Asia fell drastically in share of global activity, having accounted for 31% of total transaction value between July 2019 and June 2020, a time when it was by far the world’s biggest cryptocurrency economy.

Eastern Asia also shows relatively low grassroots adoption over the last year. China is the highest ranking country on our Global Adoption Index at 13 after ranking fourth the previous year, the fall being largely due to declining P2P trade volumes. Hong Kong is the next highest-ranked for grassroots adoption at 39, followed by South Korea at 40 and Japan at 82.

What’s behind Eastern Asia’s fall in the world rankings? One reason could be China’s recent crackdown on the cryptocurrency industry, and in particular mining. China has historically been the biggest cryptocurrency mining country in the world, but in the last year, the Chinese government has moved to ban mining from the country, and also clamped down on trading. Concurrently, China is set to launch the world’s first blockchain-based central bank digital currency (CBDC) with the digital yuan. The digital yuan is live on a trial basis now and a wider rollout is expected at the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. We’ll explore these trends below, and analyze the factors driving cryptocurrency usage in Eastern Asia.

What drives cryptocurrency adoption in Eastern Asia?

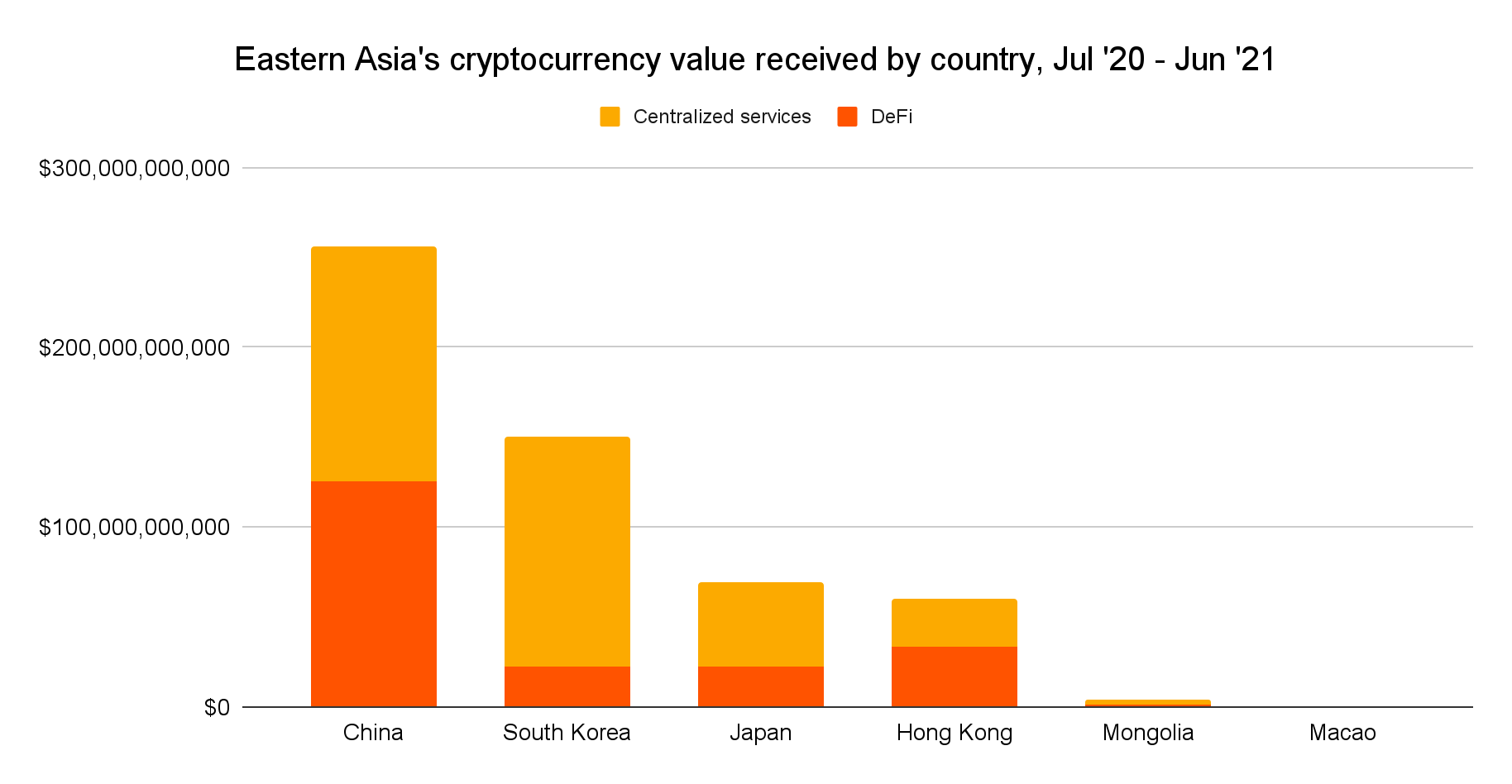

The individual countries within Eastern Asia vary by both size and preferred service type.

China is the biggest market in the region by far with $256 billion in cryptocurrency received between July 2020 and June 2021, 49% of which went to DeFi protocols. Hong Kong has a slightly higher skew toward DeFi, with 55% of its incoming $59.7 billion of cryptocurrency going to protocols.

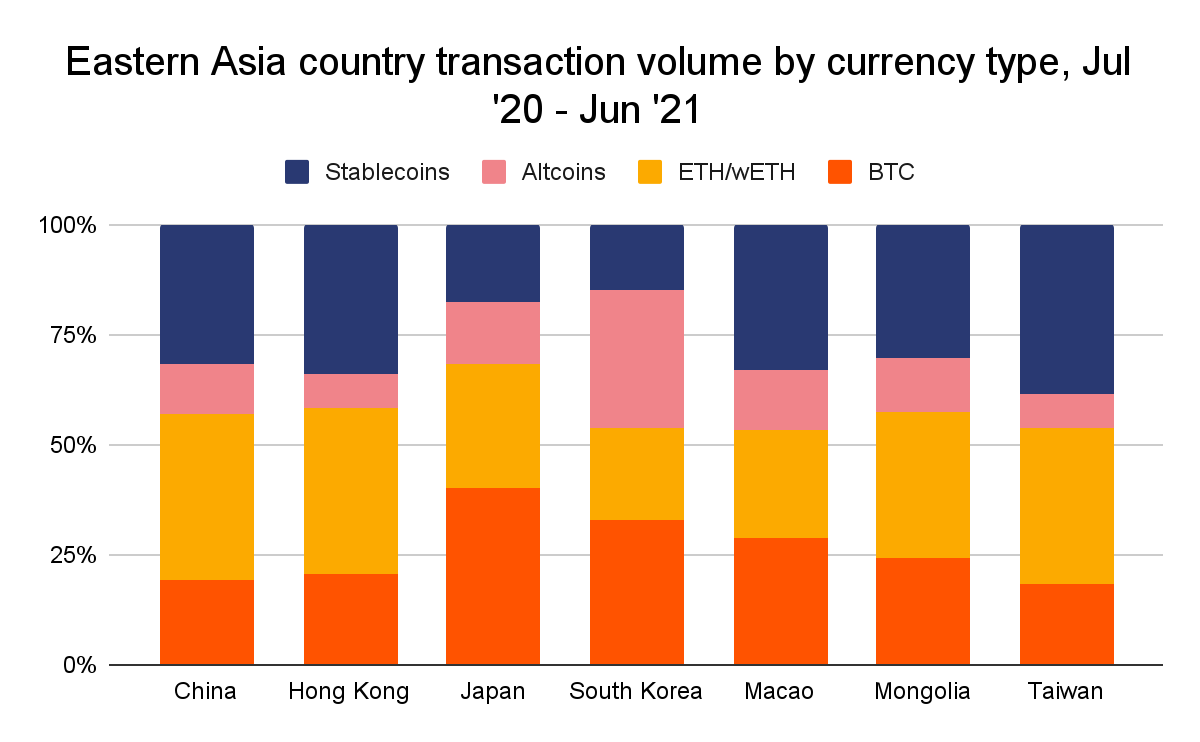

The other two notable markets in the region, however, see far less DeFi activity. Just 15% of South Korea’s $150 billion of cryptocurrency received went to DeFi protocols, while that figure rises to 32% for Japan. The breakdown of each country’s preferred currency types aligns with those trends as well.

Ethereum and wETH account for 21% of South Korea’s cryptocurrency transaction volume and 28% of Japan’s, versus 38% for both China and Hong Kong. We would expect to see that discrepancy because Ethereum and wETH are the primary cryptocurrencies for DeFi transactions. A CoinTelegraph article published in May attributes DeFi’s relative failure to gain traction in South Korea to the country’s uniquely isolated cryptocurrency market. Oleg Smagin, Head of Global Marketing at South Korean cryptocurrency lending and staking firm Delio, explained this phenomenon to the publication. “2019 became a tipping point for the wide adoption of DeFi globally,” he said. “But in Korea it was barely recognized, mostly because most of the local retail investors lacked experience using overseas crypto services and the adoption of stablecoins was low.” In Japan, meanwhile, DeFi remains largely unregulated, which may contribute to its own lagging adoption.

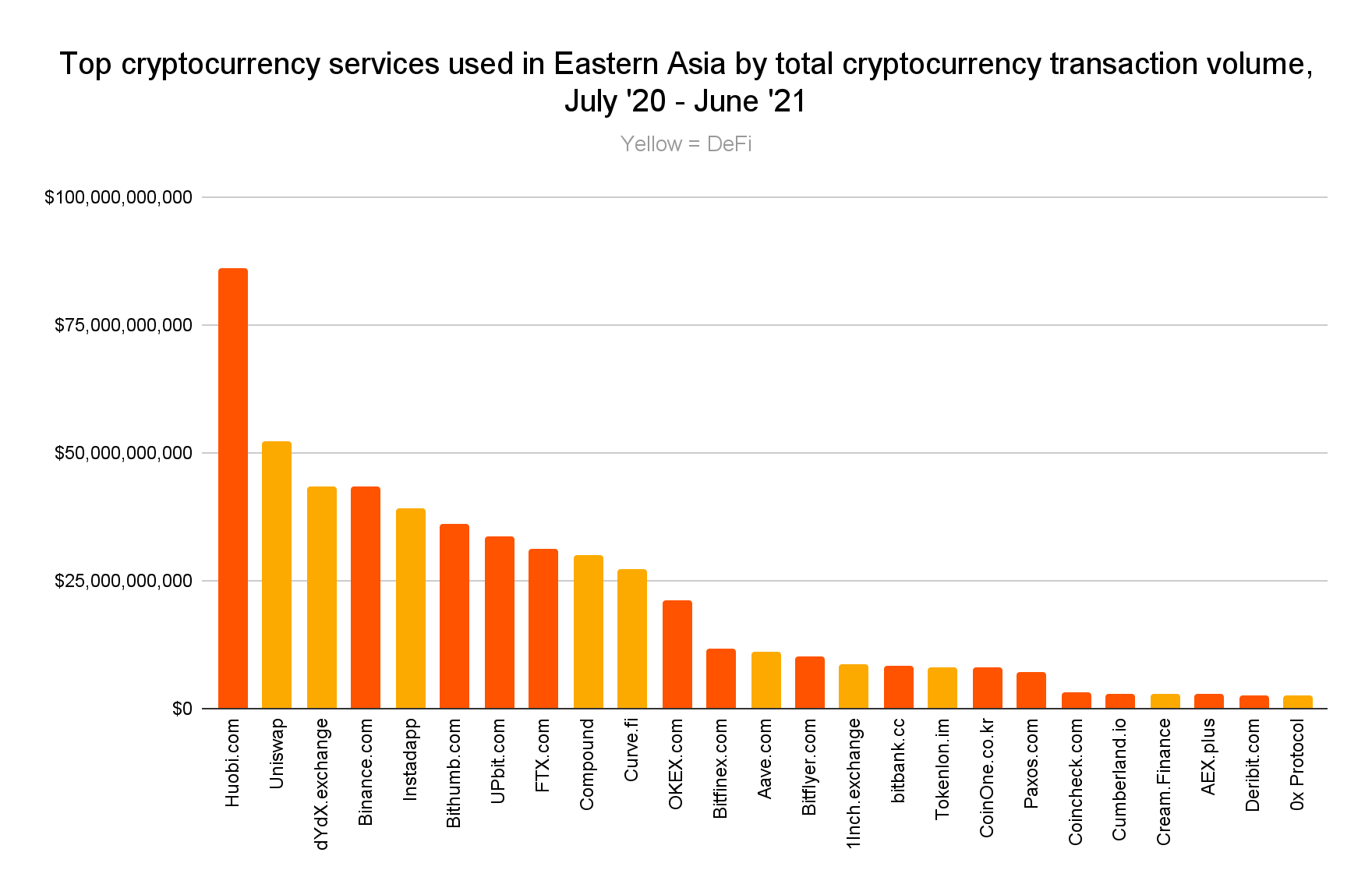

Still, overall adoption trends in Eastern Asia, led by China, have propelled several DeFi platforms to become some of the most popular in the region.

Centralized exchange Huobi remains the biggest Eastern Asia service by transaction volume, but DeFi protocols Uniswap and dydx take the second and third spots.

Mining declines in China led to less liquidity

China has historically dominated cryptocurrency mining. At times, China-based mining operations controlled as much as 65% of Bitcoin’s global hashrate — the measurement of how much computing power goes toward mining Bitcoin — which has led to increased liquidity for cryptocurrency services serving China and Asia as a whole.

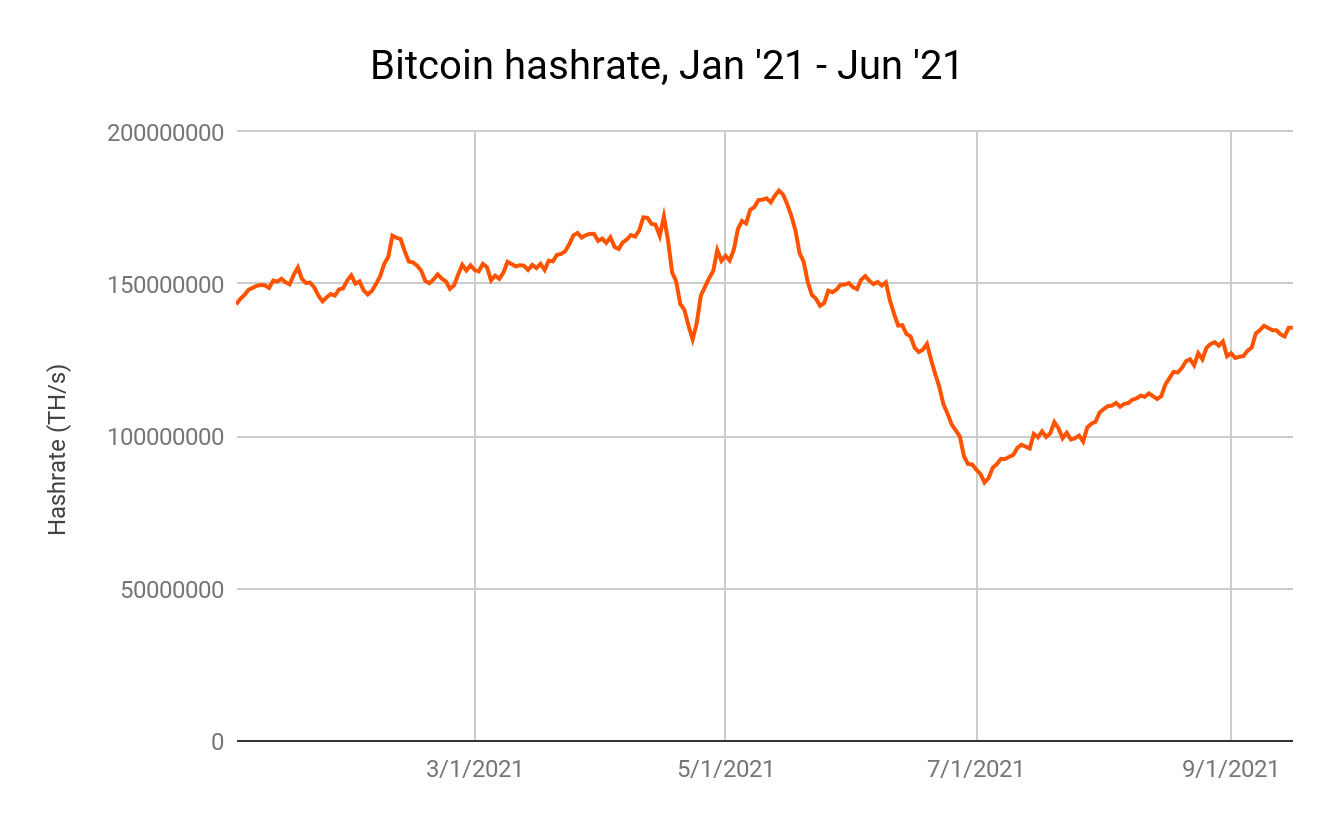

However, China’s status as the top cryptocurrency mining country changed drastically in May 2021, when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) announced its intent to clamp down on cryptocurrency mining and trading, citing concerns around financial stability and environmental impact. While this isn’t the first time the CCP has adopted anti-cryptocurrency policies, previous enforcement only pushed exchanges and other cryptocurrency businesses out of the country, while traders and miners could still operate. Following the crackdown in May 2021, Bitcoin’s overall hashrate fell by more than 50%, and while it has since rebounded, it remains below its pre-crackdown peak.

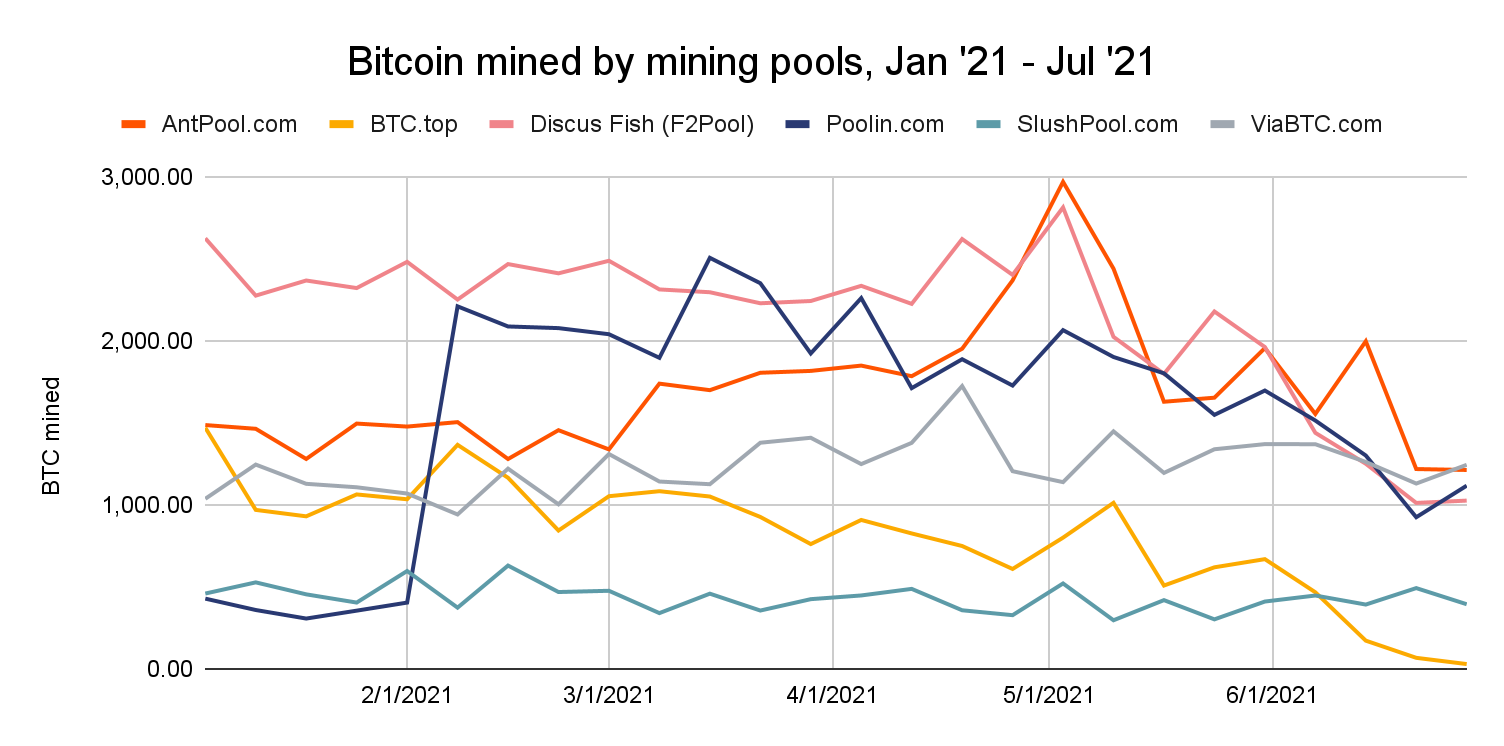

Blockchain analysis can give us a better idea of which mining pools specifically suffered the most. The chart below shows Bitcoin mined by the six biggest mining pools in the months leading up to and immediately following the crackdown.

AntPool, Poolin, BTC.top, and F2Pool, all of which are primarily based in China, seem to have seen the steepest declines, while the Czech Republic-based SlushPool has remained steady.

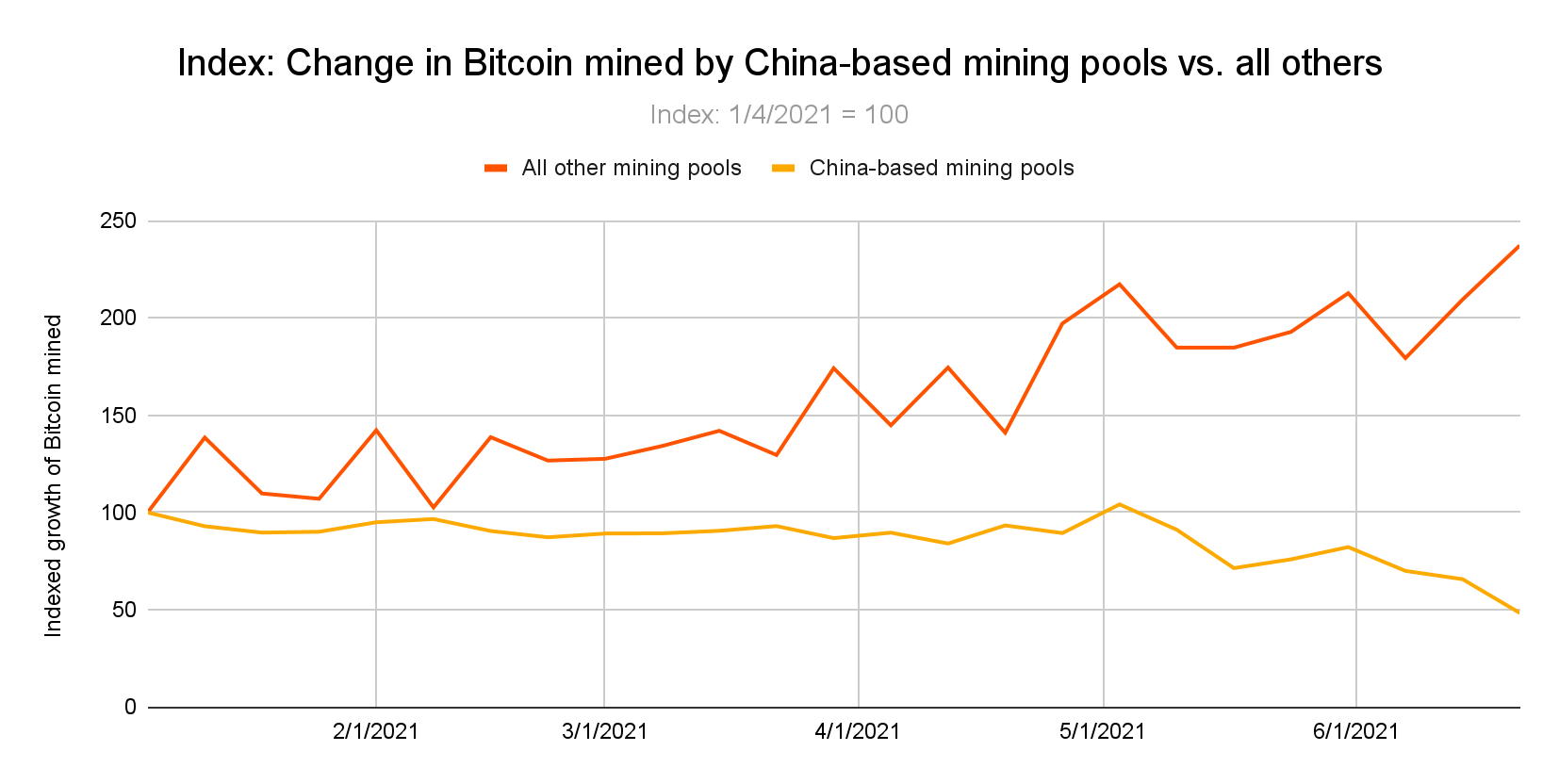

In the index chart below, we expand our analysis to the top 20 mining pools worldwide, and compare the relative growth and contraction of all those based in China versus those based elsewhere.

Since the beginning of the year, top 20 mining pools based outside of China have seen their mining proceeds more than double, while those based in China have seen proceeds decline by roughly 50%. Keep in mind, however, that in raw numbers, China-based mining pools together have still mined much more Bitcoin than others, as there are many more of them — 14 of the top 20 are based in China. Still, their revenue has declined significantly while mining pools outside of China have gained.

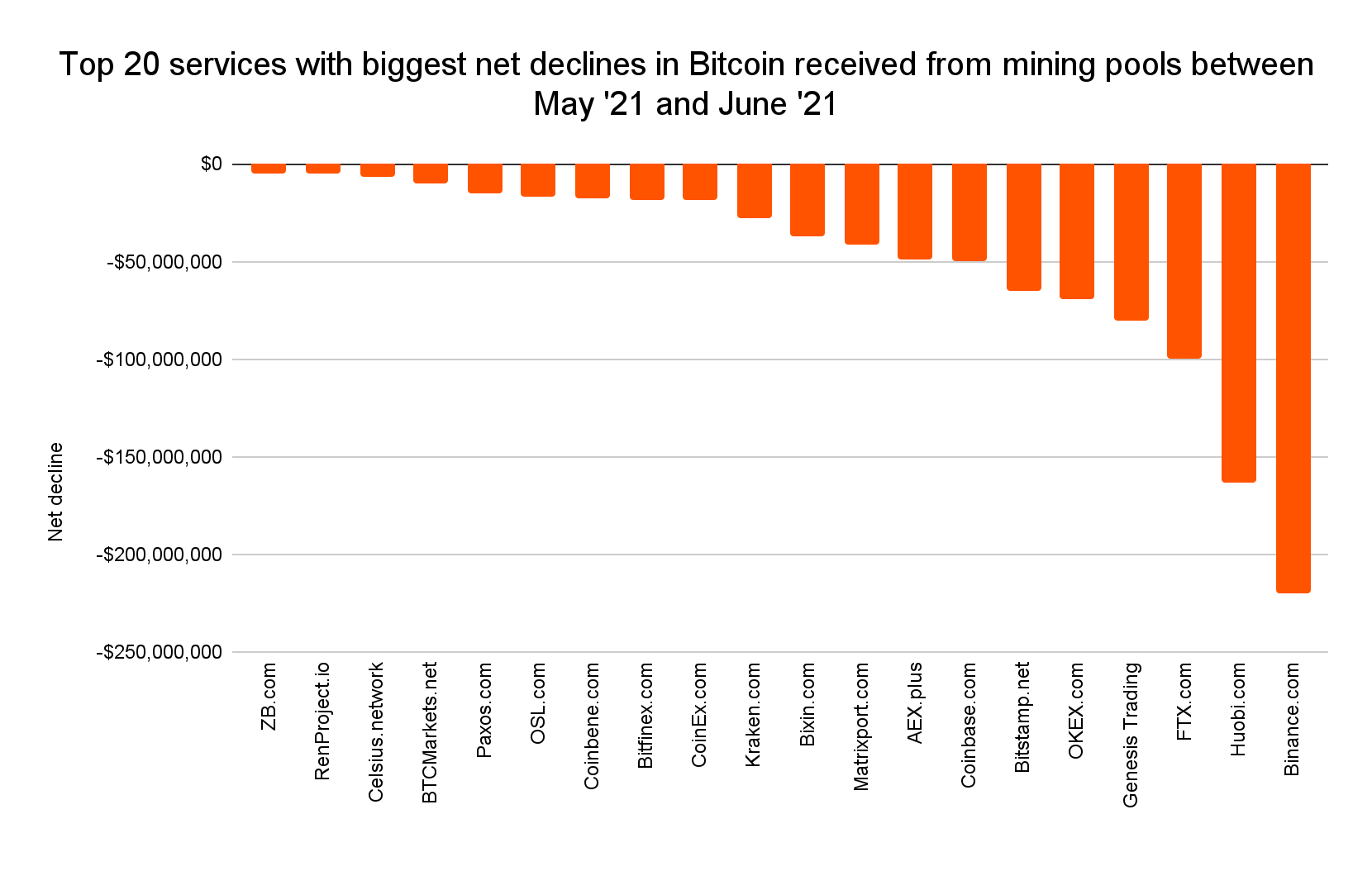

China-based mining pools have historically been an important source of liquidity for the services to which they send newly-mined cryptocurrency, which also tend to be those popular in China and East Asia generally. One significant knock-on effect of China’s mining crackdown is that many of these services appear to not be receiving cryptocurrency they otherwise would have. The chart below shows the 20 services that suffered the biggest drop offs in Bitcoin received from mining pools in June 2021, the month following the crackdown.

Binance suffered the most, with a net decline of over $200 million worth of Bitcoin received from miners, followed by Huobi, FTX, and Genesis. All of those services, in particular Huobi, are extremely popular in Eastern Asia. The loss of liquidity could account for some of the region’s decline in activity.

Of course, mining isn’t the only part of China’s cryptocurrency economy affected by the crackdown. The government has taken other actions such as campaigning against cryptocurrency in state-sponsored media, placing official warning messages on cryptocurrency-related apps, and potentially leaning on social media companies to suppress cryptocurrency-related content. These could also contribute to the country’s decline in cryptocurrency activity.

Why is China launching a digital yuan?

In April 2020, China began testing the digital yuan, becoming one of the first governments to issue a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). CBDCs like the digital yuan are government-issued, blockchain-based versions of a country’s national currency. Like most conventional cryptocurrencies, CBDCs would provide greater transparency into how people spend in the aggregate, as the currency’s blockchain would act as a permanent, immutable ledger of all transactions. China is rolling out the digital yuan through state-owned banks and digital payment apps like WeChat Pay and AliPay, which are much more widely used in China than their American or European counterparts. Digital yuan trials are ongoing, with many pointing to Beijing’s 2022 Winter Olympics as the government’s occasion to unveil its new CBDC to the world, as it plans to issue the digital yuan to visiting athletes. As of July 2021, trial users have created more than 20 million digital yuan wallets and executed over $5 billion worth of transactions with the new CBDC.

CBDCs have far-reaching implications for both domestic and foreign policy, especially when rolled out by an authoritarian regime that sees itself as a growing economic rival to the United States. We spoke to Dovey Wan, a founder of cryptocurrency investment firm Primitive Ventures and noted expert on the Asian cryptocurrency market, and asked her what she believes the CCP hopes to achieve with the digital yuan. She outlined two key goals.

The first is relatively benign: more granular control over the economy. Under the fractional reserve banking system all countries use today, central bankers can only interact with the economy indirectly, such as by changing interest rates. If the monetary supply existed entirely in CBDC form, with all transactions recorded on one central ledger, central bankers could exert more control over financial flows. “It would make monetary policy programmable,” says Wan. “For instance, if the government wanted to cool down the stock market, they could write a few lines of code and stop money from flowing into the stock market.” In addition, Wan pointed out that the digital yuan is meant to be easier for older citizens to use than the mobile payment apps that are so common now, and also cited the CBDC’s potential to make transactions cheaper for merchants by eliminating the need for third party transaction settlement.

However, it’s easy to see how a centralized, government-owned ledger of citizens’ transactions could become a tool for financial surveillance in the CCP’s hands. While Chinese citizens don’t have financial privacy under their current banking system, the digital yuan would give the government the ability to exclude individuals or businesses from the financial system for any infraction. While it’s unclear if or how much the CCP would elect to use this ability, the possibility of a “financial death sentence” would exist under the digital yuan system.

We also spoke with Yaya Fanusie, an Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) who has studied the digital yuan and published a report on the project in January 2021. Fanusie largely agreed that the digital yuan could be a tool of authoritarianism, but put more emphasis on its role in the CCP’s broader desire to collect as much data as possible on citizens. “There’s never been a centralized database for a government to access records of all citizens’ transactions,” says Fanusie. “Yes, China can request that data from mobile payment apps, but that takes time, and sometimes they push back.”

He also outlined ways financial data generated by the digital yuan could be combined with other types of data that feed into China’s controversial social credit system. “The CCP recently released a notice that Mongolian families who didn’t send their children to state-mandated schools would be put on a blacklist. The digital yuan would allow the government to combine financial data with lists like that.” Fanusie mentioned that the CCP has already voiced its intention to use the digital yuan to monitor for corruption in the government. While that sounds like a reasonable goal, one can easily imagine how those financial surveillance capabilities could be turned on ordinary citizens.

This blog is a preview of our 2021 Geography of Cryptocurrency report. Sign up here to download the whole thing!