This blog is an excerpt from the Chainalysis 2020 Geography of Cryptocurrency Report. Sign up here and we’ll email you the full report as soon as it comes out in September!

East Asia is the world’s largest cryptocurrency market, accounting for 31% of all cryptocurrency transacted in the last 12 months. East Asia-based addresses have received $107 billion worth of cryptocurrency in the last 12 months, which is 77% more than Western Europe, the second-highest receiving region. Much of this can be attributed to the region’s stranglehold on mining activity. China alone controls 65% of Bitcoin’s global hashrate — the measurement of how much computing power goes toward mining Bitcoin — which means that the majority of all newly-mined Bitcoin starts out at Asia-based addresses, giving the market a massive liquidity boost.

East Asia’s trading volume is driven by a robust professional market, but as we’ll explore, the retail market is also extremely active. The liquidity of the East Asia market also makes it the closest we have to a self-sustaining market. 44% of transactions by volume involving an East Asia-based address are counter-partied with another East Asia-based address, compared to just 22% for Western Europe, the next closest region. The liquidity and large trading population of the East Asia market makes it a key trading partner for other regions’ cryptocurrency economies — in fact, East Asia is either the largest or second-largest counterparty for every other region we study in this report. The mining dominance we discuss above is one source of East Asia’s liquidity, as it means a steady stream of newly-mined cryptocurrency is always traveling to East Asia addresses.

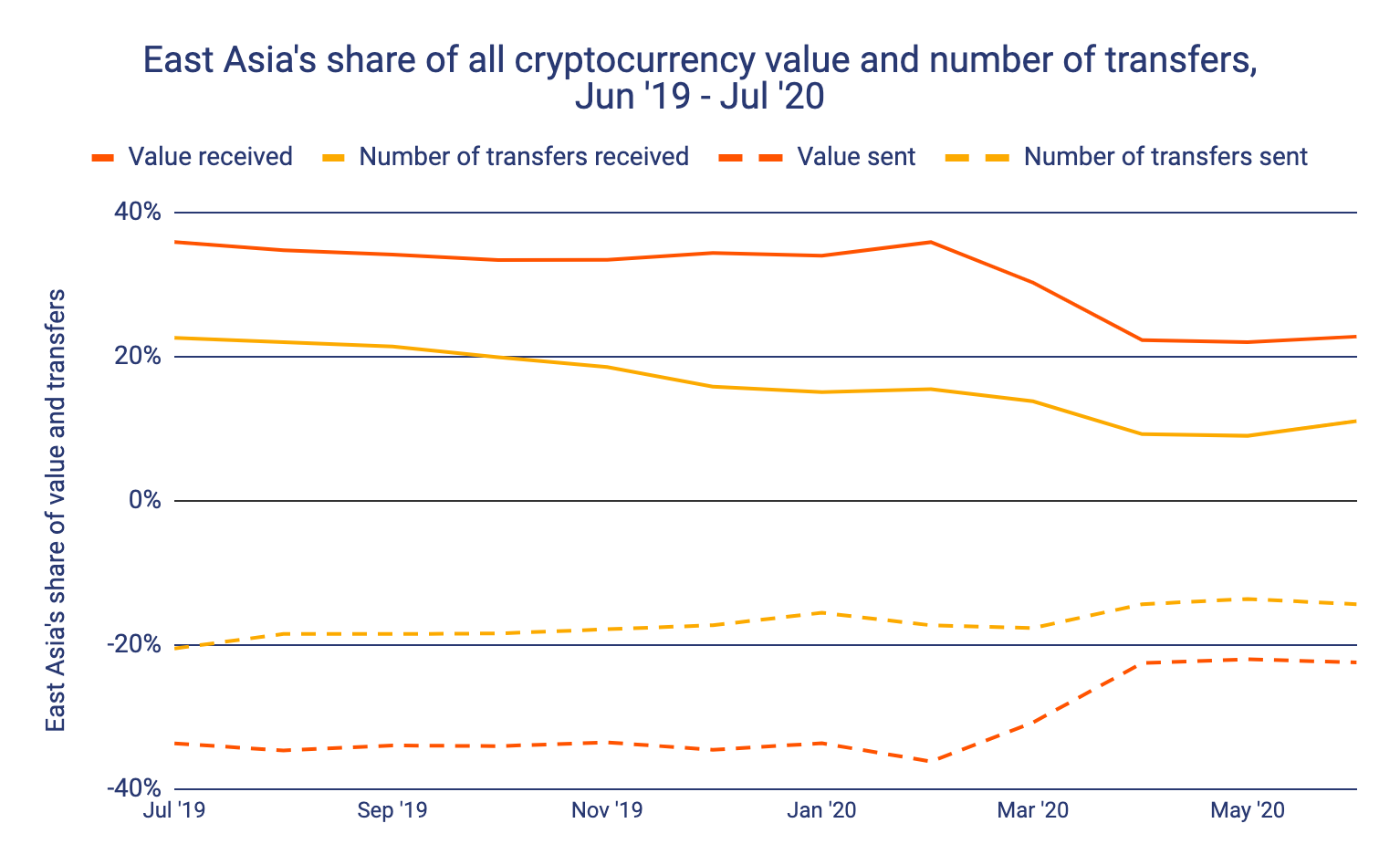

Still, East Asia’s share of global cryptocurrency activity has slipped somewhat over the last 12 months, in part because other regions are catching up, but also due to some stagnation in its professional market, the reasons for which we’ll explore below. In addition, we’ll examine the unique role stablecoins play in the East Asian market, as well as other key differences between professional traders in the region versus others we study.

Professional traders with heavy altcoin focus dominate East Asia

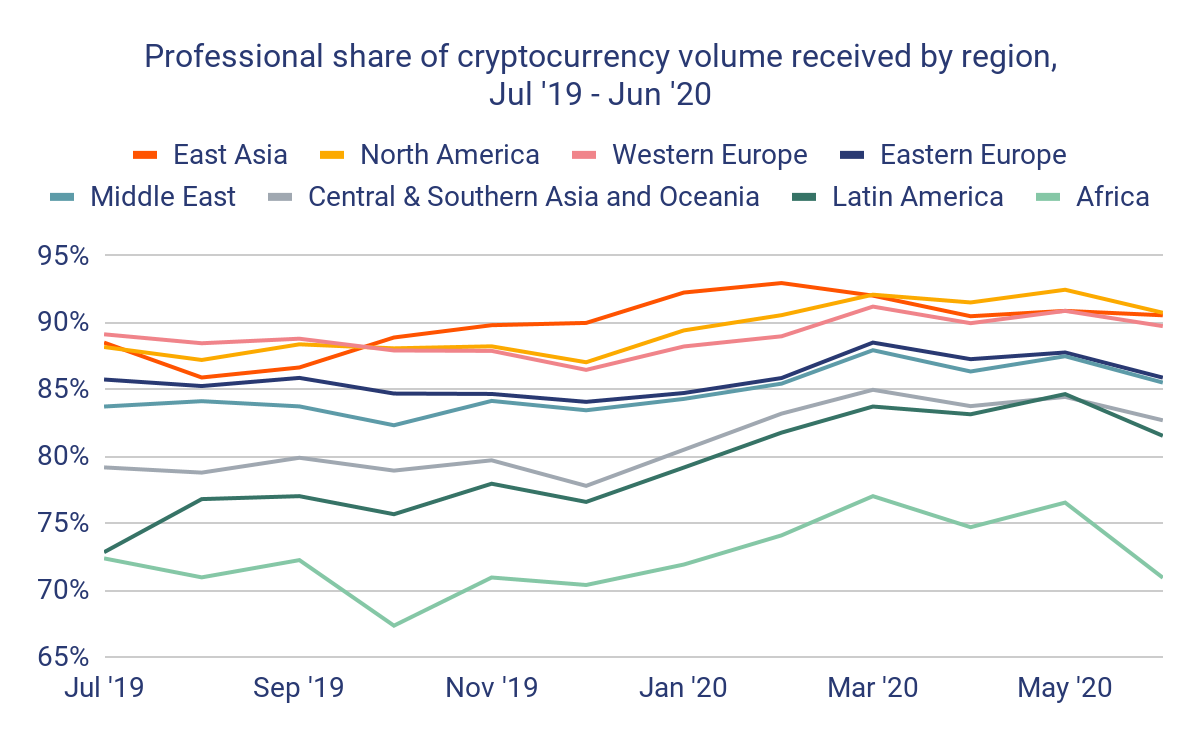

The East Asia cryptocurrency market is dominated by professional traders, with roughly 90% of all volume transferred by East Asia in any given month attributed to professional-sized (above $10,000 USD worth of cryptocurrency) transfers. Only North America and Western Europe have matched or exceeded that share of market going to professional traders in the last 12 months.

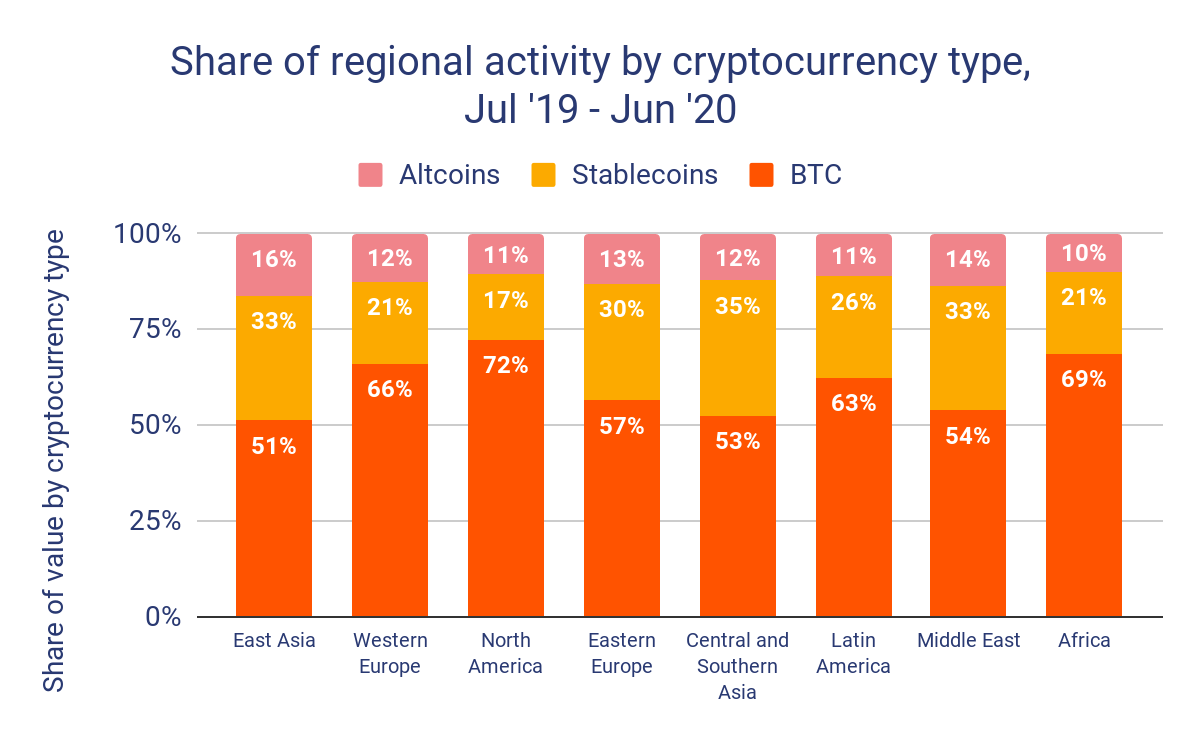

Interestingly, professional cryptocurrency investors in the East Asian market appear to engage in more speculative trading of a wider variety of assets compared to similar regions like North America, where the pros tend to focus more on Bitcoin and hold for longer. In the chart below, we see a comparison of transfer volume by type of cryptocurrency for each region.

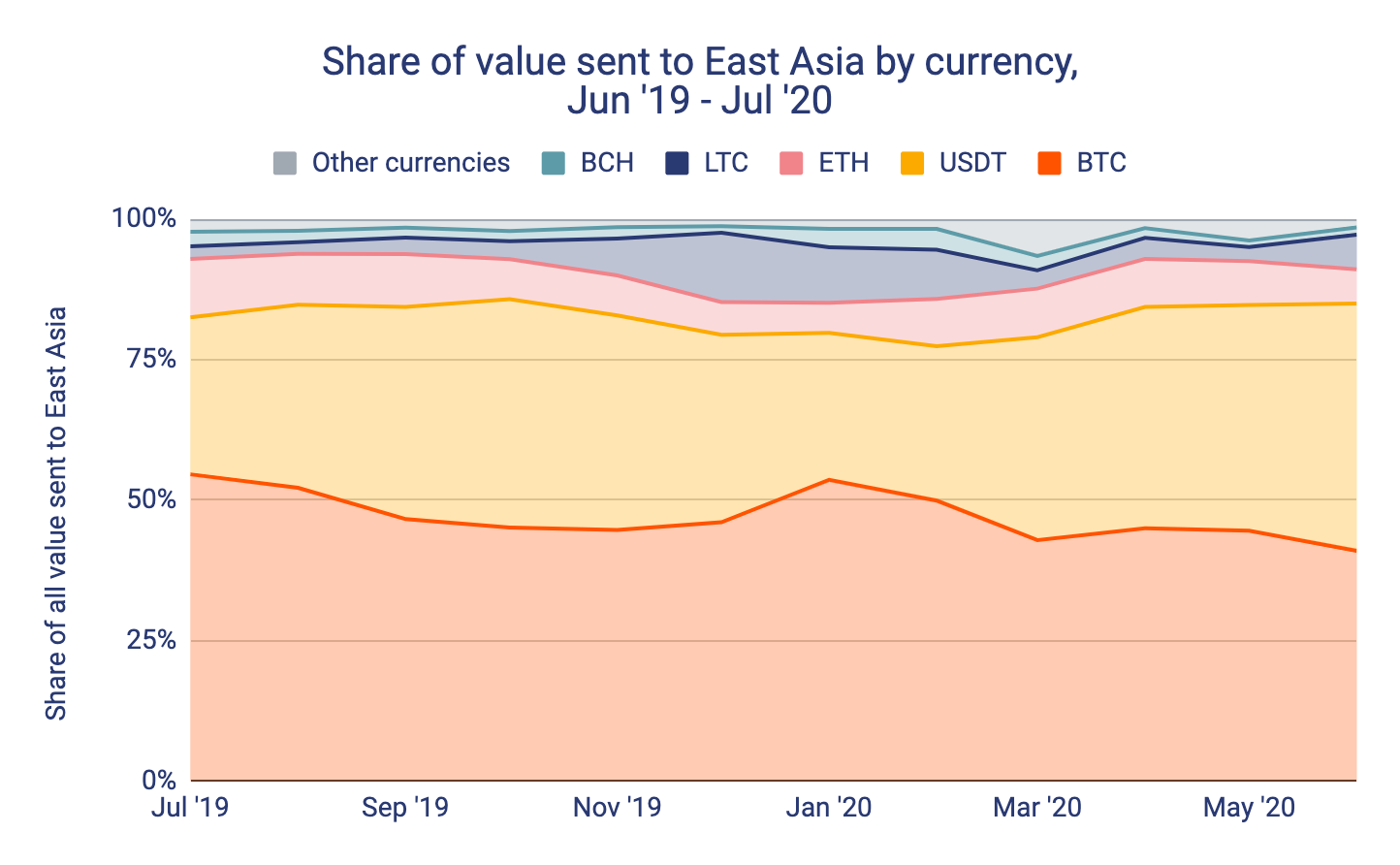

East Asia has the lowest share of on-chain volume devoted to Bitcoin at 51% of transfers by volume. Of the three comparably-sized regions, Eastern Europe comes closest with 57% of transfers made up of Bitcoin. North America and Western Europe, on the other hand, comprise 72% and 66% of all transaction volume with Bitcoin respectively. As we’ll explore later, much of the remaining volume is made up of stablecoins — primarily Tether — but the chart above also underscores the role altcoins play in the East Asia market. Altcoins, by which we mean all non-stablecoin alternatives to Bitcoin, make up 16% of trading volume for Eastern Asia addresses, more than any other region. Litecoin specifically makes up a 2.9x larger share of trading volume for East Asia than the average share across all other regions. That same figure is 1.9x for Crypto.com Coin, 1.3x for Maker, and 1.2x for Bitcoin Cash.

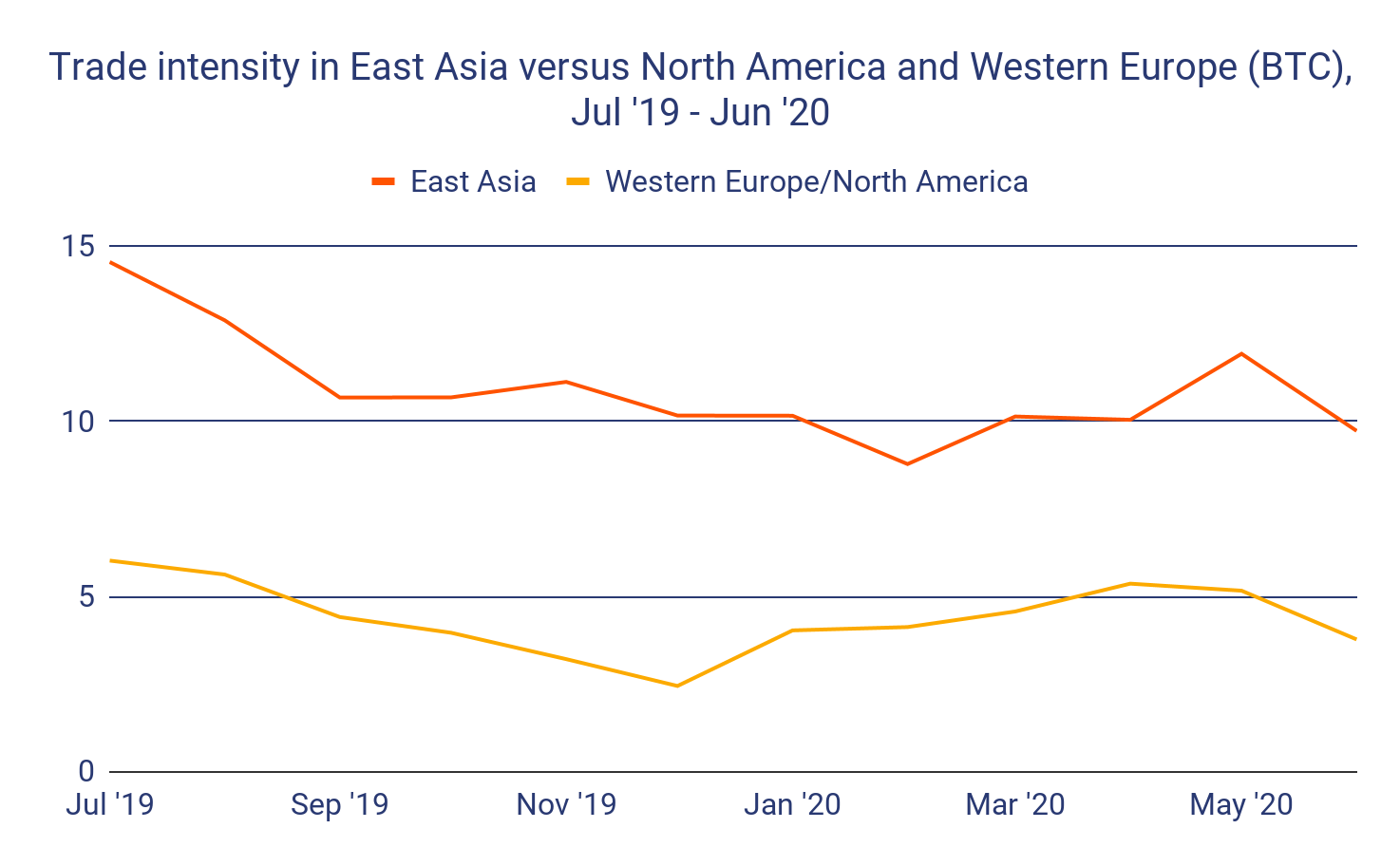

Traders based in East Asia also appear to trade more frequently. Below, we compare the Bitcoin trade intensity of five exchanges with predominantly East Asia-based users to that of five with predominantly North America and Western Europe-based users. Trade intensity measures the number of times each coin deposited on an exchange is traded within the exchange before exiting, and can help us understand how much an exchange’s users tend to hold versus trade.

The East Asian exchanges have a trade intensity between 1.4x and 3.8x higher than those catering to North America in any given month over the last year, showing that East Asia cryptocurrency users trade more frequently than those in North America, who tend to buy and hold.

However, while the professional market dominates in East Asia, its retail market is still one of the largest in the world, as countries like China, Japan, and Korea have seen substantial adoption amongst everyday users. Why is this? Krishna Sriram, Head of Partnerships at Japan-based cryptocurrency security firm Quantstamp, attributes it in part to pre-existing electronic payments infrastructure. “Services like AliPay in China and LINE in South Korea were already quite popular by the time cryptocurrency began to gain steam, so the idea of electronic money wasn’t as big of a leap,” she told us in an interview. “Despite not having as much of an electronic payments precedent, Japan also saw strong early adoption, as many Japanese corporations saw the value of cryptocurrency and set up mining operations. Japanese regulators set out clear rules early, which helped exchanges grow there quickly.”

Still, the East Asia cryptocurrency market does appear to be sagging somewhat in comparison to other regions over the last 12 months.

While East Asia is still the biggest cryptocurrency market by a wide margin, it’s share of overall activity has declined since October 2019. We asked regional expert and Primitive Ventures Founding Partner Dovey Wan why this might be. One reason she cited was fallout from the PlusToken scandal. PlusToken was a notorious Ponzi scheme that netted over $2 billion worth of cryptocurrency from millions of victims, mostly concentrated in Asia. Wan indicated that this dampened some of the positive sentiment around cryptocurrency in the region.

Perhaps most interestingly though, Wan told us that in China specifically, uncertainty around the government’s plans for cryptocurrency have many cryptocurrency entrepreneurs putting projects on hold. In October 2019, right around the time East Asia’s share of the global cryptocurrency market begins to decline, Chinese President Xi Jinping gave a speech indicating the country may launch a digital yuan — in other words, a digital version of the Chinese national currency with its own blockchain, also known as a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) — which could mean the government won’t allow or support new coins. “Undertones matter. It’s important that Xi talked about ‘the blockchain’ but not ‘Bitcoin.’ It implies that the digital yuan will be the only official, state-sanctioned cryptocurrency and dampens the view of crypto as a private asset,” she said. Wan believes that this sentiment has prevented new coins from launching, as entrepreneurs feel safer starting neutral blockchain-adjacent companies rather than new cryptocurrencies or exchanges.

Stablecoin usage is off the charts

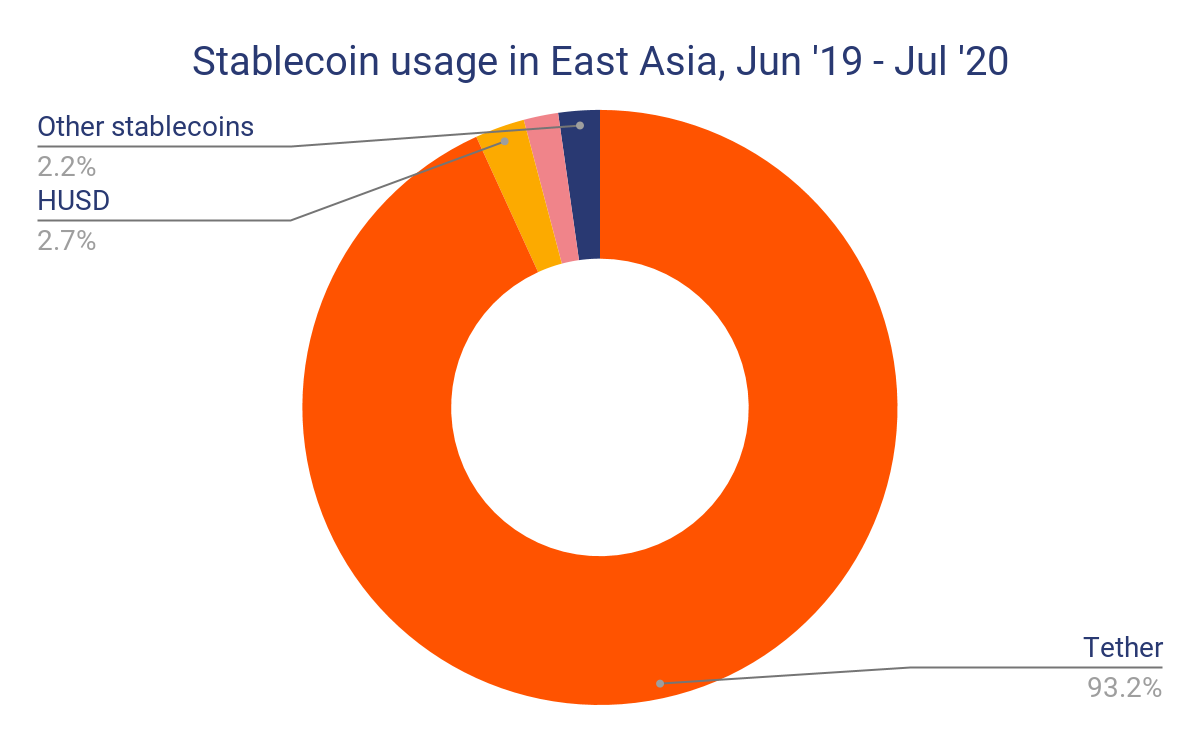

As we touched on above, stablecoin usage is especially high in East Asia, making up 33% of all value transacted on-chain. That share has been rising over the last few months though, with Tether — a popular stablecoin pegged to the U.S. dollar — actually beating out Bitcoin to be the most-received cryptocurrency by East Asia-based addresses in June 2020.

Tether is by far the most popular stablecoin in East Asia, making up 93% of all stablecoin value transferred by addresses in the region.

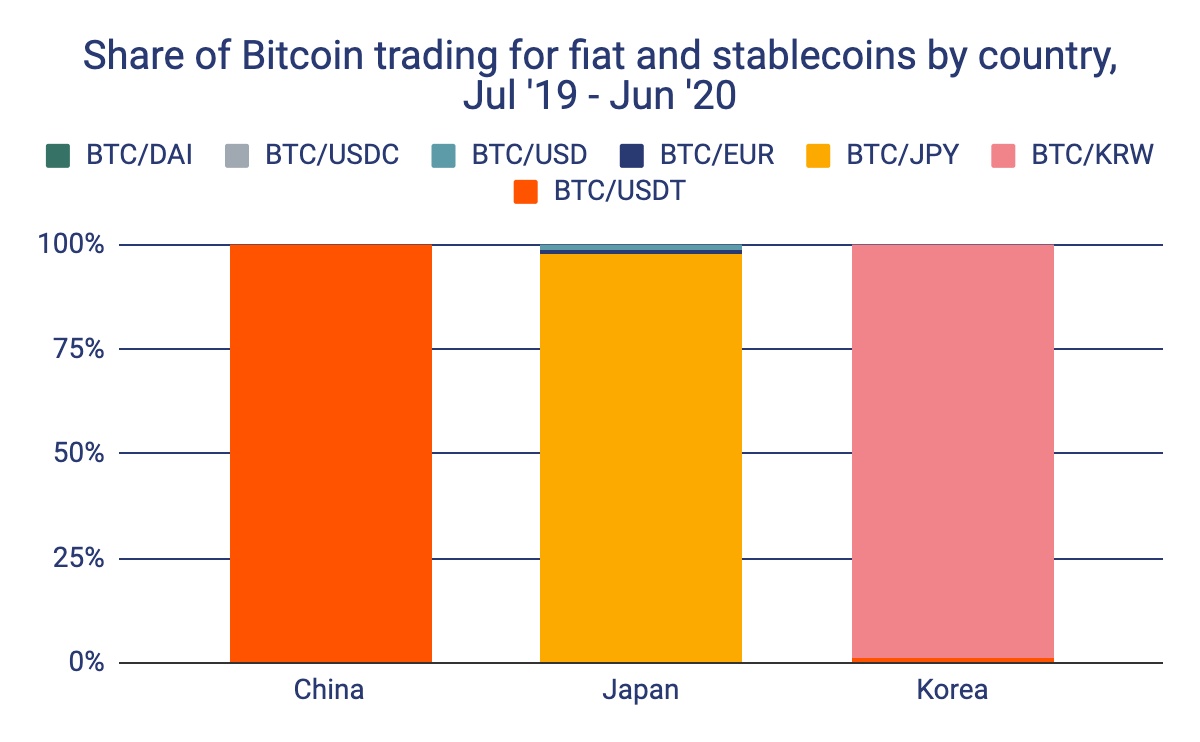

As we discussed in our 2019 APAC report, much of stablecoins’ popularity in East Asia stems from the Chinese government’s decision in 2017 to ban direct exchanges of yuan for cryptocurrency. As a result, Tether has become the de facto fiat stand-in for Chinese cryptocurrency users and primary means of on-ramping to Bitcoin and other standard cryptocurrencies. Though yuan-for-Tether trades are also not allowed under the ban, it’s common for users to buy Tether under the table from OTC brokers or through other means such as by using a foreign bank account. By using Tether as a fiat stand-in instead of, say, Bitcoin, traders can lock in gains without off-ramping into fiat by simply converting other currencies into Tether and leaving the Tether in their wallet or exchange account. Bitcoin, by contrast, has too much price volatility for this to be feasible. We see this in the chart below, which compares the most popular fiat-crypto trading pairs (with Tether counted as a fiat currency) on exchanges in China, Japan, and South Korea.

Paolo Ardoino, CTO of Tether, discussed this phenomenon with us and said, “Tether tokens are neither a panacea nor a replacement for fiat. Instead use cases have organically grown where traditional financial assets have been found to be lacking. Tether tokens may not be best suited for buying coffees, but the fast settlement, deep liquidity, low fees and stable price associated with tethers have created unique opportunities for crypto traders, remittances, lending products and safe havens for people in jurisdictions with less stable fiat currencies.”

While traders, specifically prop traders, represent Tether’s primary use case, we have identified significant secondary use cases as well. Krishna Sriram at Quantstamp told us that ordinary users in emerging markets both in and out of East Asia use Tether as a means of value storage, as well as for cross-border remittances. As we’ll explore in greater detail later, some of those international payments may represent capital flight from countries like China.

When we spoke to Dovey Wan about East Asia’s outsized Tether usage, she agreed the yuan trading ban was a major factor, and also pointed out Tether’s effectiveness for carrying out everyday transactions. “Tether has become a U.S. dollar replacement for many people in China. Lots of Chinese businesses and merchants, especially those working overseas, now accept Tether from customers,” she told us. Without knowing the cryptocurrency addresses of businesses accepting Tether for transactions, we can’t know exactly how big this use case is today, though the evidence suggests most Tether volume moved is related to trading. But the fact that this use case appears to be developing organically for Tether speaks to stablecoins’ potential as a medium of exchange.

However, all of this begs the question: Why Tether over any other U.S. dollar-pegged stablecoin? Wan indicated to us that many popular cryptocurrency influencers in China have historically been big proponents of Bitfinex, whose parent company also owns Tether. Many of those influencers became wholesalers of Tether, selling the stablecoin to a large network of OTC traders around China. Those OTC traders in turn sell Tether to the masses. “It’s very decentralized,” says Wan. “There’s usually one go-to OTC broker in each town, and they’ve played a big role in facilitating Tether’s everyday use over the last year.”

East Asia, led by China, trades heavily with other regions

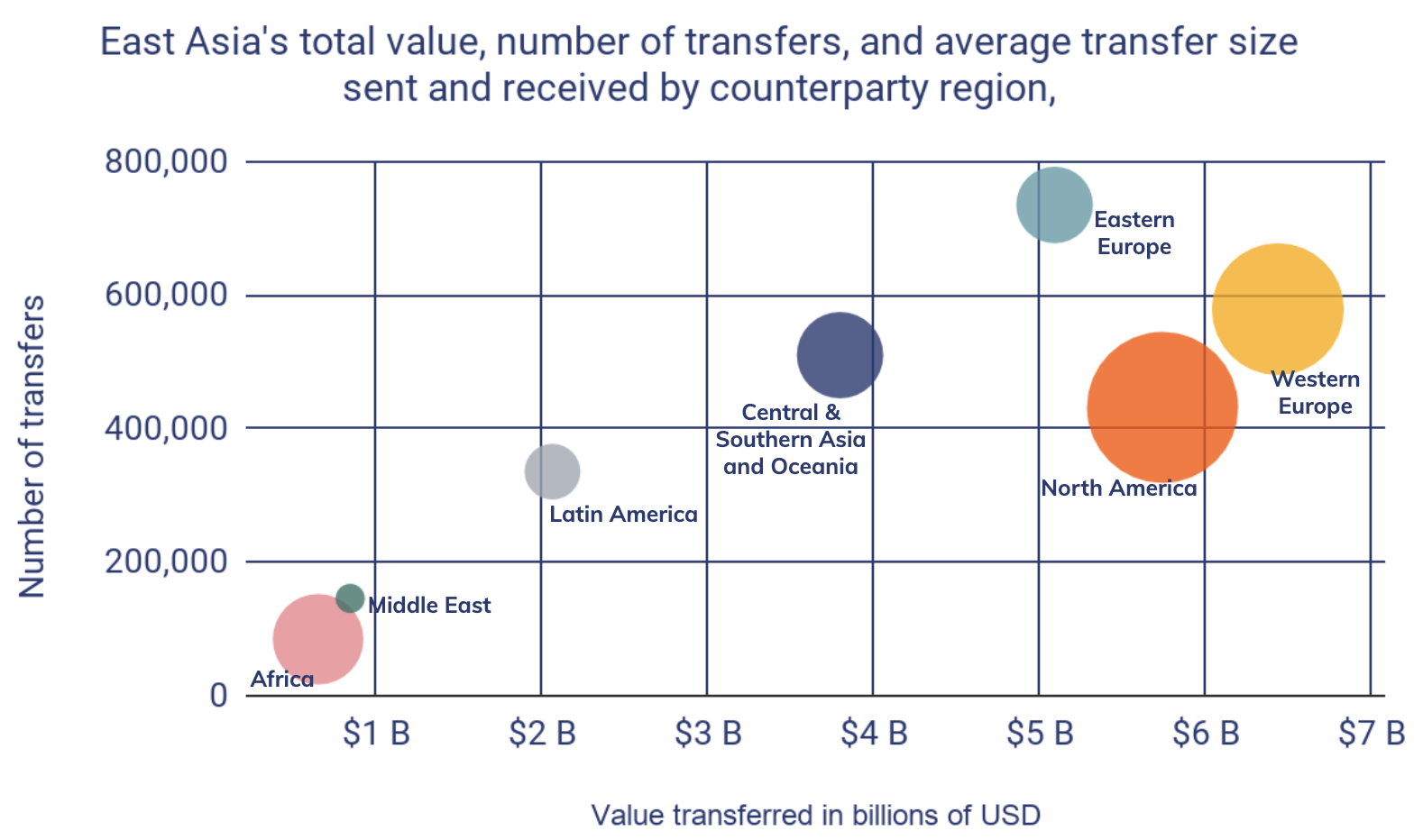

East Asia is arguably the linchpin of the global cryptocurrency market. With 78% higher trading volume than the next closest region, it has liquidity to spare and sends more cryptocurrency around the globe than any other region, despite also having the highest proportion of trading that occurs within the region.

Let’s look more closely at East Asia’s relationship with other regions.

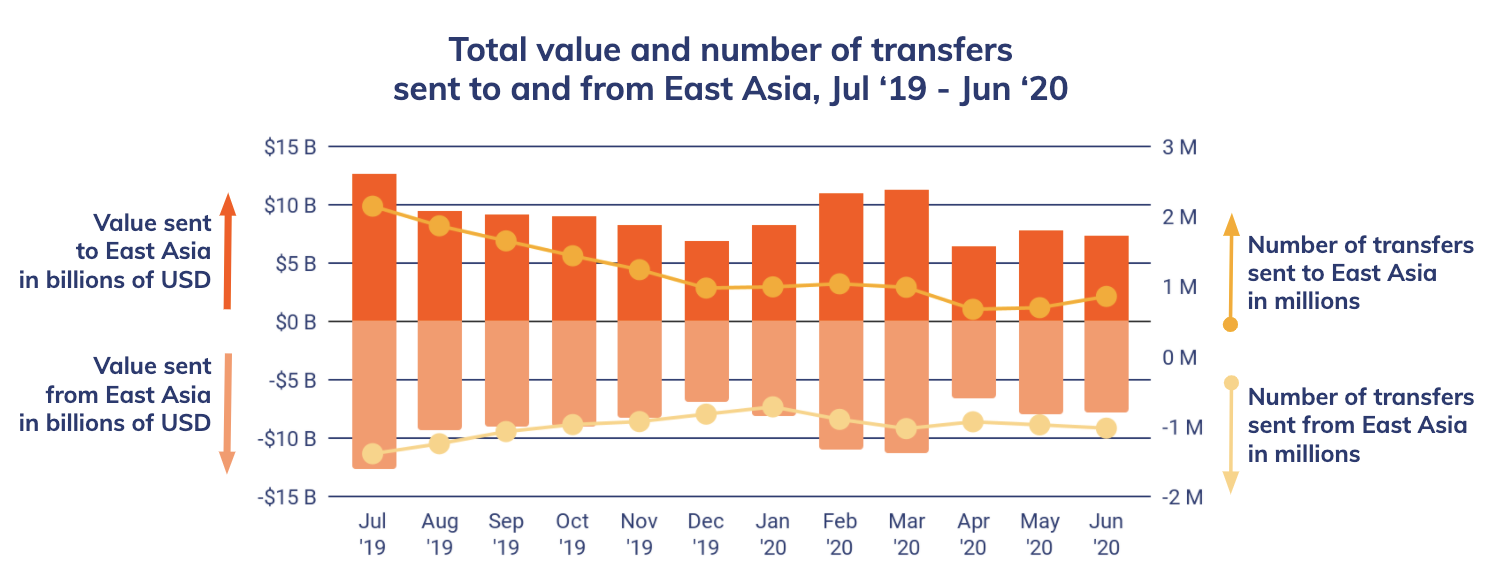

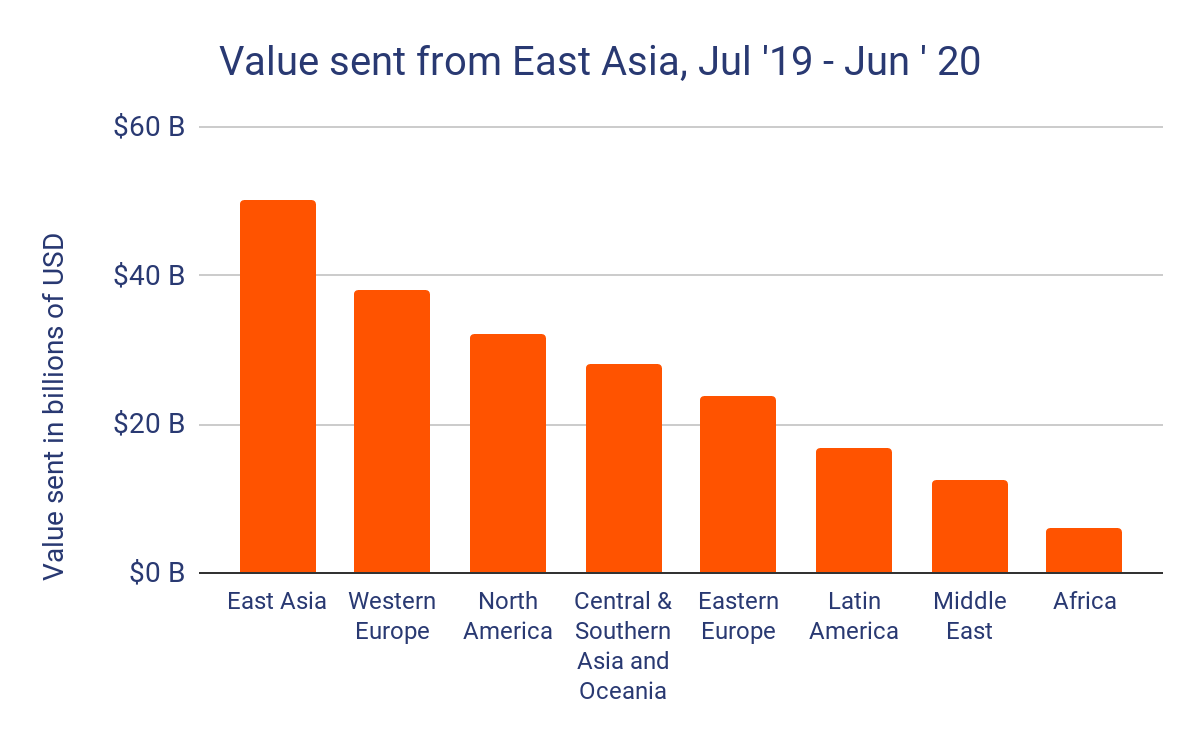

Despite having the highest proportion of domestic activity, East Asia still sends more cryptocurrency to foreign addresses than any other region. Over $50 billion traveled from East Asia addresses to addresses in other regions, compared to just over $38 billion for Western Europe, the region next in terms of value sent out of region. Some of this is undoubtedly related to East Asia’s mining dominance — it makes sense that a significant share of the newly mined cryptocurrency coming from East Asia would go to North America and Western Europe, as these are the next-largest cryptocurrency markets. However, we believe that at least some of this activity represents capital flight from China.

The Chinese government only allows citizens to move the equivalent of $50,000 USD or less out of the country each year. Historically, wealthy citizens have gotten around this through foreign investments in real estate and other assets — sometimes even using shell companies to carry out investments — but the government has cracked down on some of these methods. Cryptocurrency could be picking up some of the slack though.

Over the last twelve months, with China’s economy suffering due to trade wars and devaluation of the yuan at different points, we’ve seen over $50 billion worth of cryptocurrency move from East Asia-based addresses to overseas addresses. Obviously, not all of this is capital flight, but we can think of $50 billion as the absolute ceiling for capital flight via cryptocurrency from East Asia to other regions.

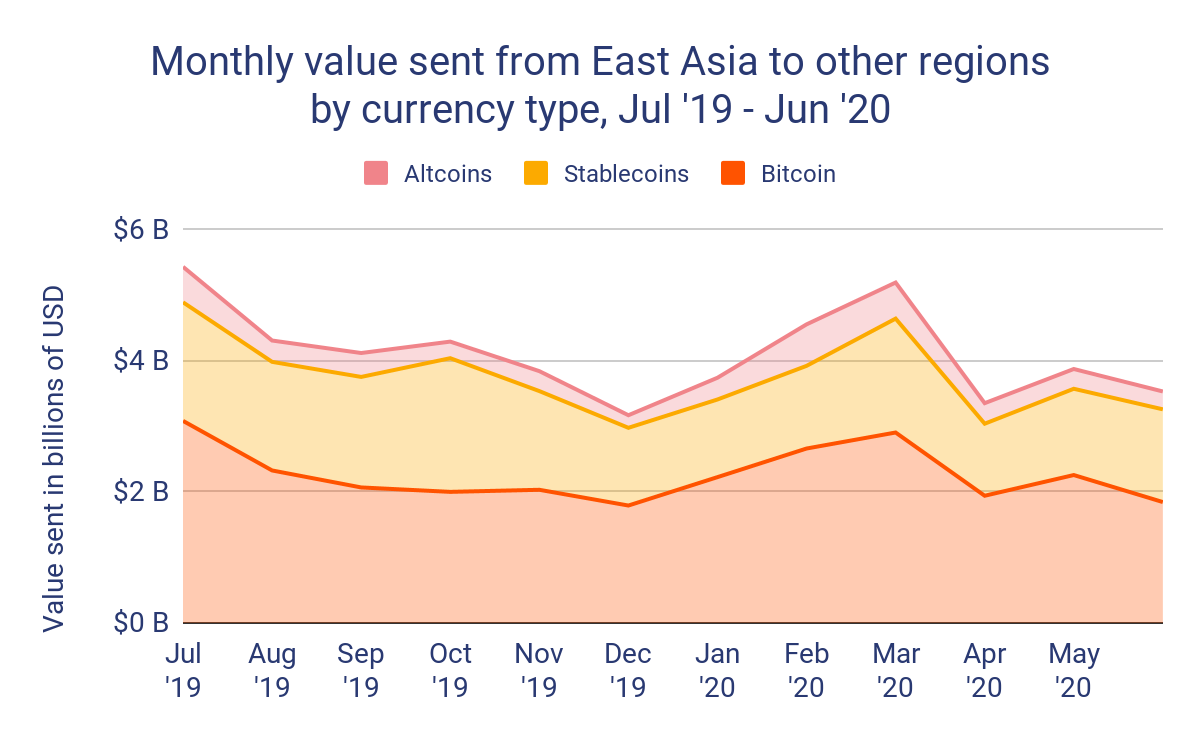

We also see above that stablecoins make up a significant portion of East Asia’s cryptocurrency sent overseas. That isn’t too surprising since, as we covered above, stablecoins — especially Tether — are disproportionately popular in East Asia compared to other regions. However, stablecoins are particularly useful for capital flight, as their fiat currency-pegged value means users selling off large amounts in exchange for their fiat currency of choice can rest assured that it’s unlikely to lose its value as they seek a buyer. Grayscale Director of Research Philip Bonello told us that anecdotally, users in many regions use stablecoins for capital flight, in addition to other forms of cross-border remittances. “Anecdotally, it appears that users in many regions use stablecoins to access US dollars for cross-border payroll, remittance, and capital flight from local currencies,” he told us.

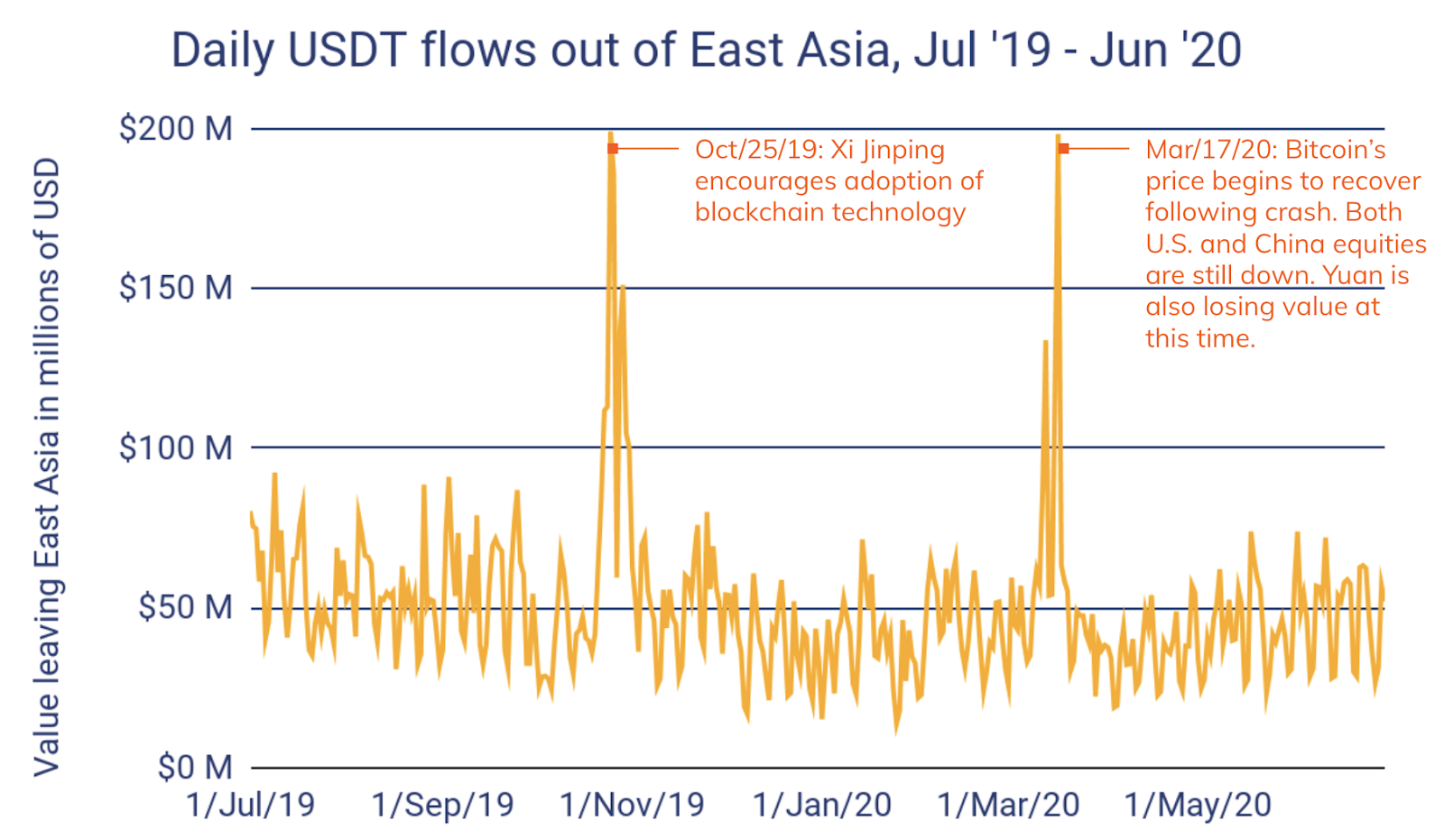

Given stablecoins’ conduciveness to capital flight, and the fact that Tether is by far East Asia’s most popular stablecoin, we look below at the amount of Tether that has moved from East Asia addresses to foreign addresses over the last 12 months.

In total, over $18 billion worth of Tether has moved from East Asia addresses to those based in other regions over the last 12 months. Again, it’s highly unlikely that all of this is capital flight. Much of it is likely related to mining activity, as we’ve heard anecdotally that China-based miners or their counterparties often convert newly-mined coins into Tether before sending it on to larger exchanges serving more regions. But still, it’s interesting that we see spikes in Tether volume moved overseas that appear to correspond with news events in China that have cryptocurrency-related implications. The first occurred around October 25, soon after Chinese President Xi Jinping gave the speech we previously referenced, in which he indicated China may soon launch its own national cryptocurrency. As Dovey Wan explained, this speech may have dampened China’s cryptocurrency outlook somewhat, as it implied that there may be fewer opportunities for cryptocurrency entrepreneurship and even private ownership of cryptocurrency. Perhaps this drove some of China’s cryptocurrency community to move portions of their holdings overseas?

The second large spike occurred around March 17, a time when Bitcoin’s price was beginning to recover after having dropped from around $9,100 to under $5,000 in the week preceding due to Covid-19 uncertainties. Equities in both the U.S. and China were still losing value at this time, as was the yuan itself. It’s possible that the economic tumult may have prompted some capital flight from China, though much of the Tether movement could have been East Asia-based cryptocurrency traders moving their holdings to international exchanges in order to trade at a time when cryptocurrency price volatility was high.

Of course, these spikes could also be related to trading arbitrage. Tether Chief Compliance Officer Leonardo Real told us that, while Tether’s price is intended to remain constant at $1 USD, it can sometimes fluctuate by a few cents at times of high price movement in the wider cryptocurrency market. When this happens, primary market traders are incentivized to close the gap by selling tethers at the higher price for a profit. He also told us that Tether sometimes trades at different prices on exchanges serving different regions, and that some traders establish accounts at multiple exchanges to take advantage of these price differences for arbitrage. It’s possible that such activity and market demand for tethers, which are often highly liquid trading pairs, contributed to the two large spikes in Tether movement that occurred in the last year.

Ardoino at Tether clarified further how the currency’s journey from issue to the wider market makes it difficult to track the relative commonality of Tether’s potential use cases, adding, “Tether’s minimum value threshold for transactions means that we attract institutional clients and high net worth individuals. Our direct clients are primary market participants who are incentivized to stabilize prices through arbitrage trading whenever the price oscillates in either direction, in response to market forces. In that sense, the ability of primary market participants to acquire tether tokens or redeem them for fiat on a 1:1 ratio creates a transparent, market driven stabilizing mechanism. Secondary market participants are not verified with Tether but use tether tokens for a myriad of reasons including trading, remittances, merchant services and other use cases.”

East Asia’s relationship with the Africa and Latin America markets is also interesting. While both are two of East Asia’s smaller trade partners, East Asia is a huge source of cryptocurrency to both of them, as it’s the largest sender to Latin America and the third-largest to Africa. While some of this, especially in the case of Africa, represents remittances from expats, our interviews suggest that much of it also represents commercial transactions between Chinese businesses and their customers and partners in the region. Luis Pomata, co-founder of the Paraguay-based exchange Cripex, told us that many Latin American businesses use cryptocurrency to pay Chinese importers for goods they then sell. Ray Yousseff, founder and CEO of popular peer-to-peer (P2P) exchange Paxful, told us about similar business relationships in Africa.

In some cases, Chinese merchants living abroad are responsible for these transactions. Dovey Wan told us about Chinese cryptocurrency miners who set up shop in parts of Africa that offer cheap hydropower and send portions of their proceeds home regularly, as well as others in non-cryptocurrency businesses, such as gem mining, who do the same thing.

All of this goes to show how crucial East Asia is to the worldwide cryptocurrency economy. In the case of China, it’s particularly interesting to think about these cryptocurrency trade relationships in the context of national projects like the Belt and Road Initiative, through which the Chinese government seeks to expand its global influence by investing in infrastructure projects around the globe. Whether intended by the government or not, the data indicates that cryptocurrency may have a role to play in advancing that goal.

Want more insights into how cryptocurrency usage differs by region? Sign up here to get the full Geography of Cryptocurrency Report delivered to your inbox as soon as it comes out! You’ll get more original data and research on inter-regional trading patterns, the state of regulation by region, how cryptocurrency mitigates economic instability in the developing world, and more!