This blog is an excerpt from the Chainalysis 2020 Crypto Crime Report. Click here to download the full document!

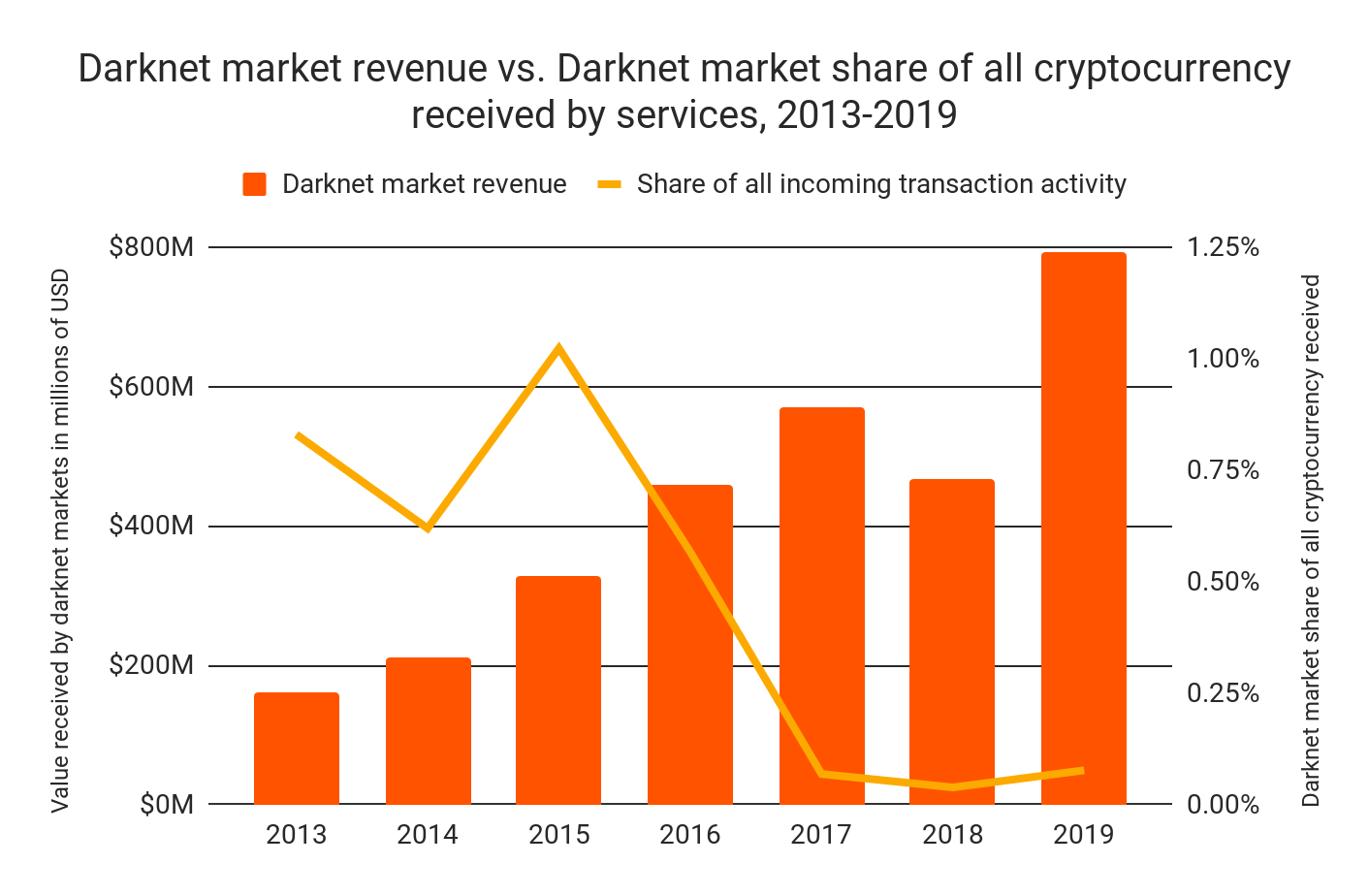

After a small decline in 2018, total darknet market sales grew 70% in 2019 to over $790 million worth of cryptocurrency, making it the first time sales have surpassed $600 million. Not only that, but for the first time since 2015, darknet markets increased their share of overall incoming cryptocurrency transactions, doubling from 0.04% in 2018 to 0.08% in 2019.

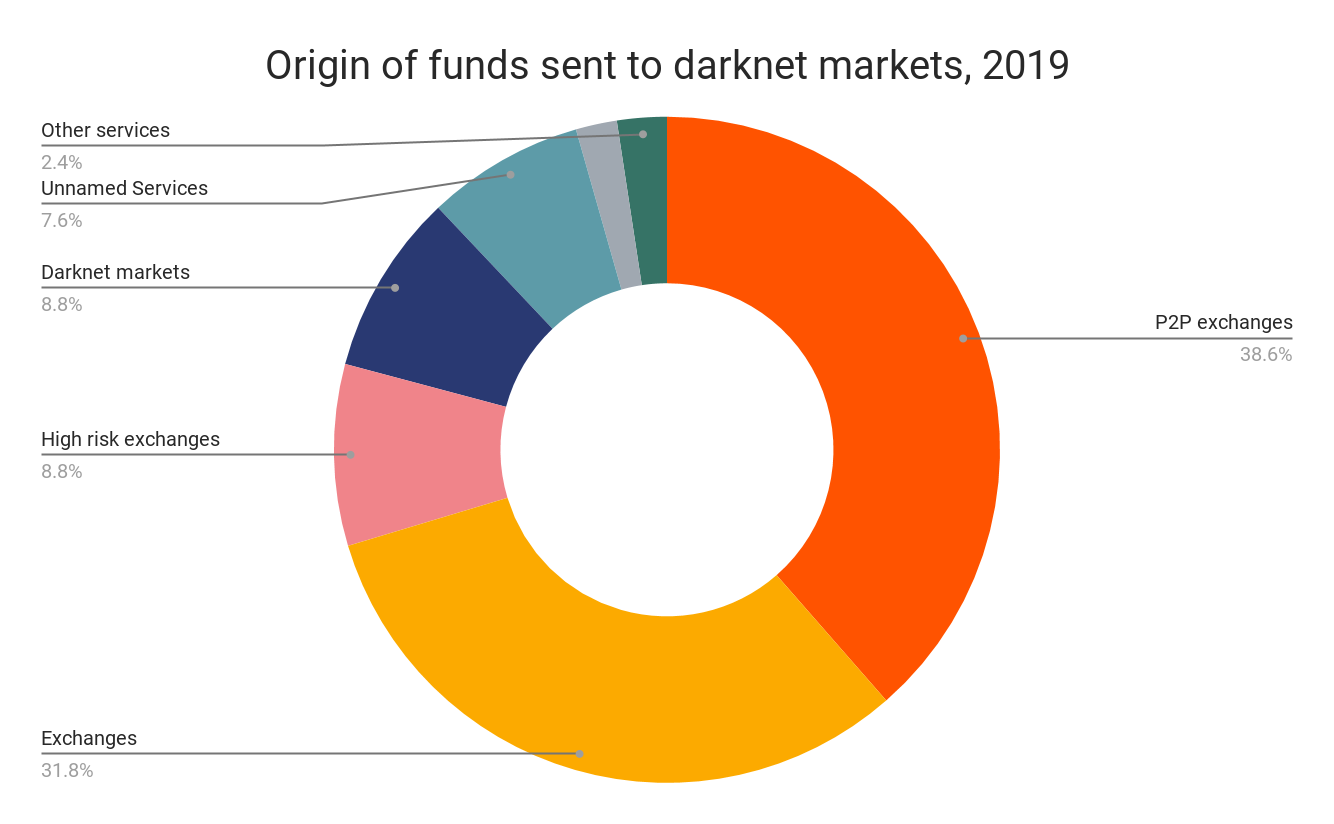

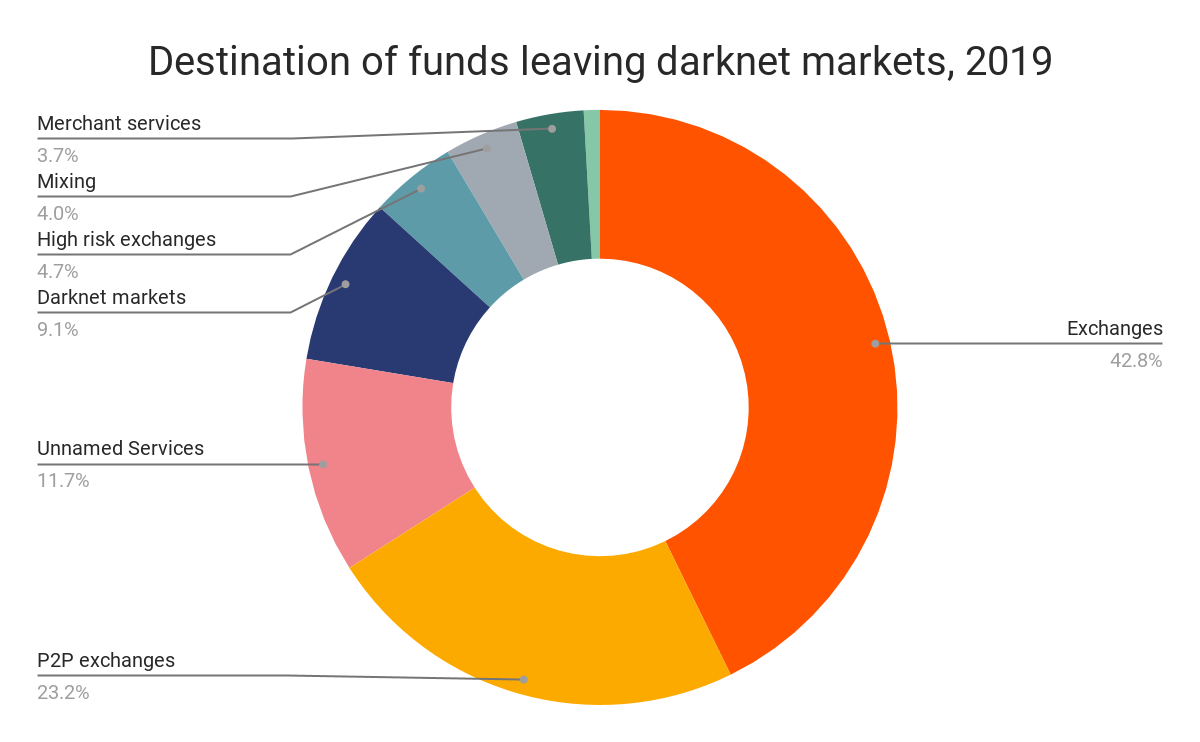

Similar to previous years, the vast majority of darknet market transactions flow through exchanges. Exchanges are by far the most common service customers use to send cryptocurrency to vendors, and for vendors to send funds to cash out.

While darknet markets’ total share of incoming cryptocurrency activity remains extremely low at 0.08%, recent increased volume speaks to the resilience of darknet markets in the face of heightened law enforcement scrutiny.

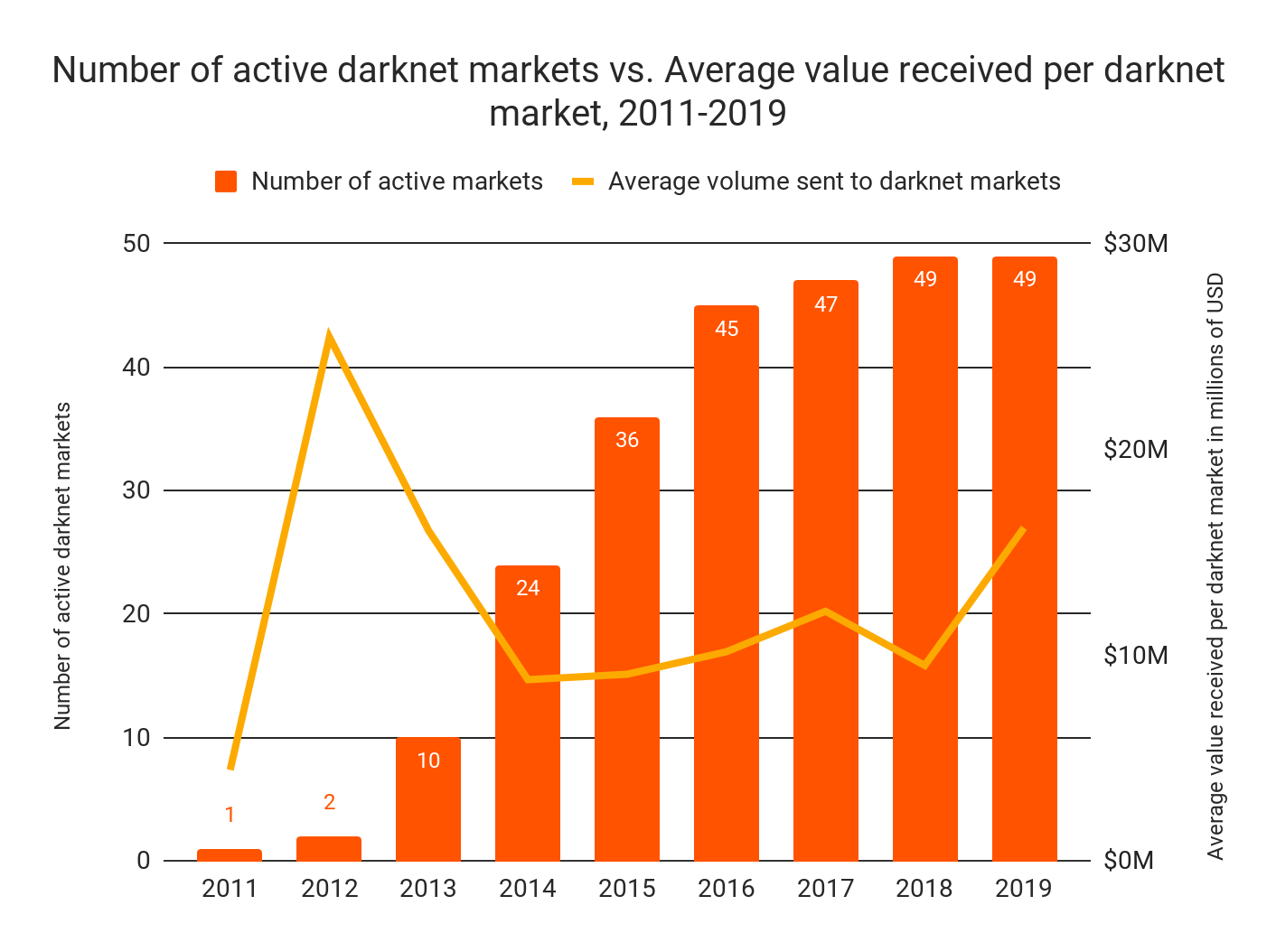

Although eight of the darknet markets active in 2018 closed in 2019, eight new ones opened, keeping the total number of active markets steady at 49. On average, each active market in 2019 collected more revenue than those active in any other year, apart from during the height of Silk Road’s heyday in 2012 and 2013. As we’ll examine in more detail later, it appears that when some markets close, others are able to pick up the slack and satisfy customer demand.

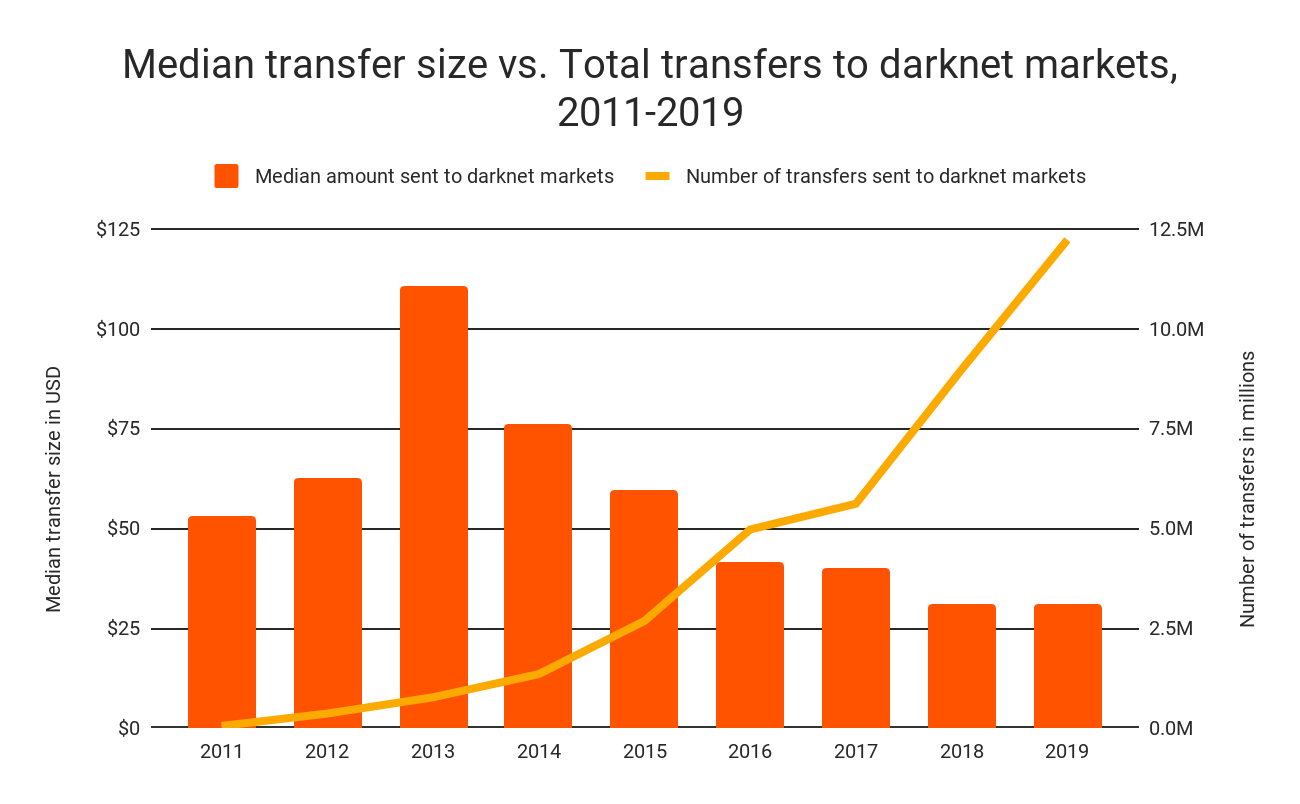

The data above also confirms that the increase in revenue is driven by more purchases rather than larger ones. The median purchase size has remained relatively constant in USD value, but we see that the number of transfers once again jumped significantly, from 9 million to 12 million. This suggests that either more customers bought from darknet markets in 2019, or that old customers are making more purchases.

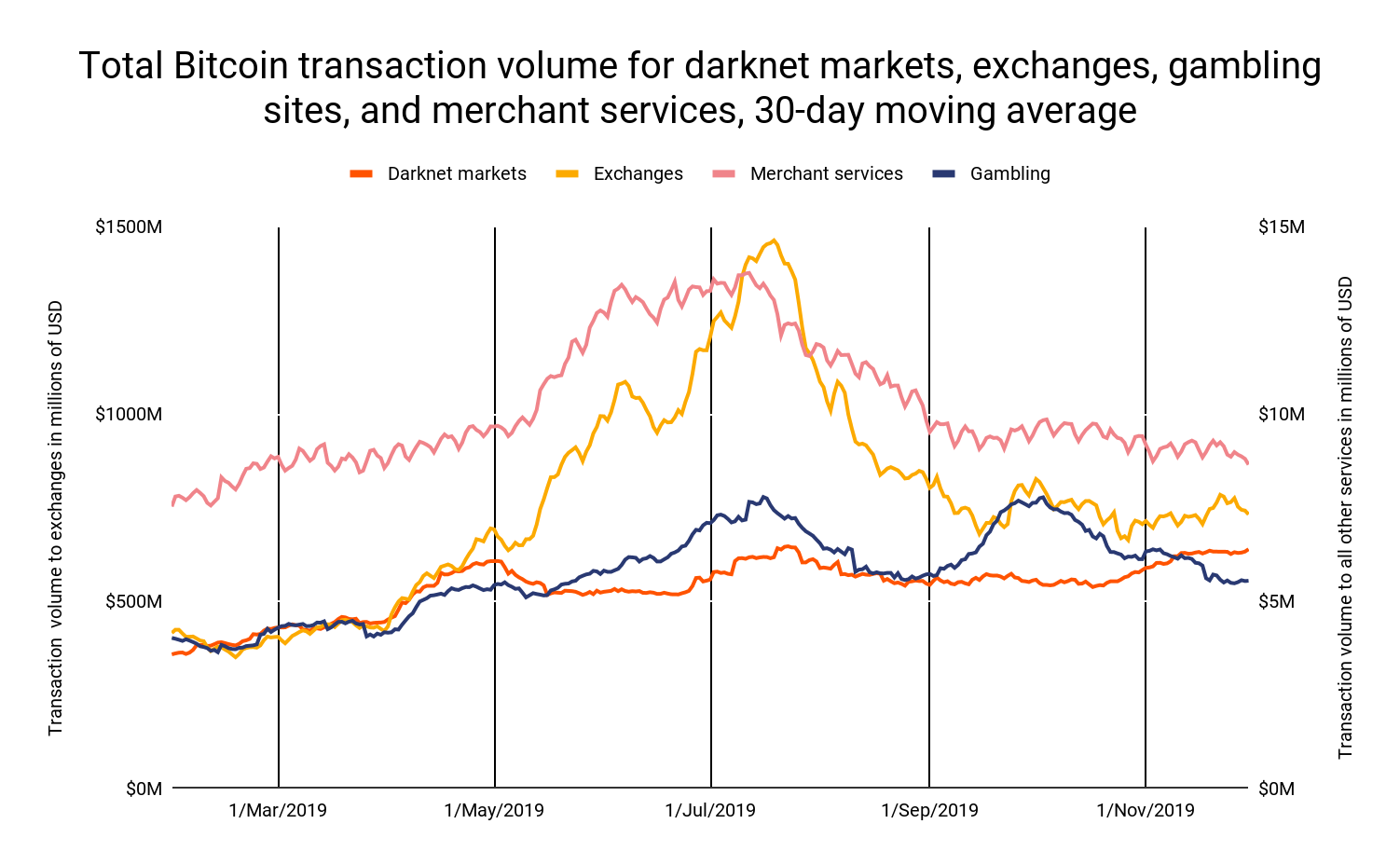

Perhaps our most interesting finding is that darknet markets’ transaction activity appears to be less influenced by the ebbs and flows of the cryptocurrency markets and other forms of seasonality compared to other services. The graph above shows a comparison of total Bitcoin transaction volume between darknet markets and three other types of services over the course of 2019. While all categories see spikes in July around the same time as a Bitcoin price surge, darknet markets exhibit a much less dramatic spike than the others. Looking across the entire year, darknet markets’ transaction activity remains within a much narrower volume range, suggesting that customer behavior is less influenced by changes to Bitcoin’s price.

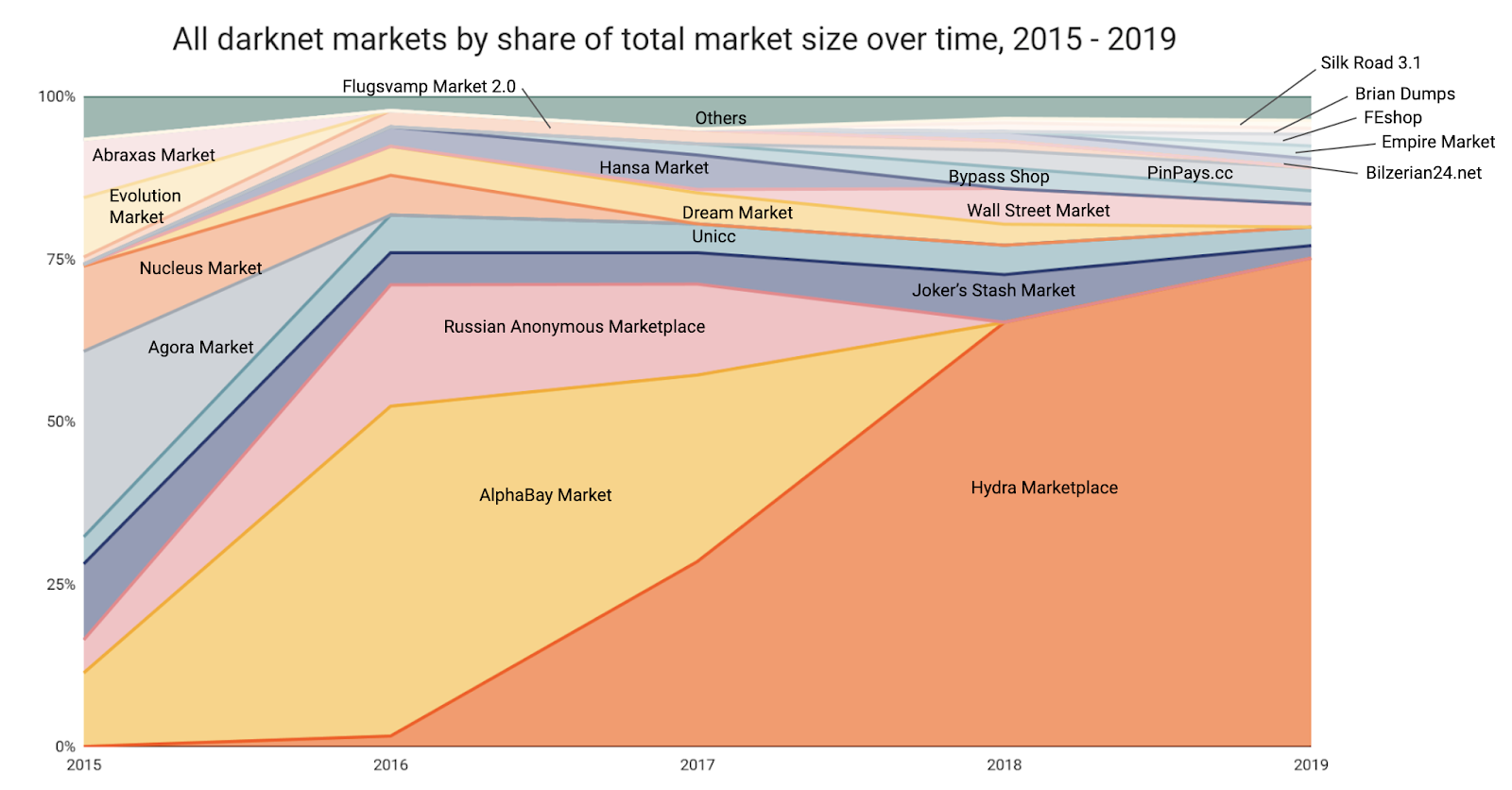

Drugs still rule the darknet, but aren’t the only inventory on offer

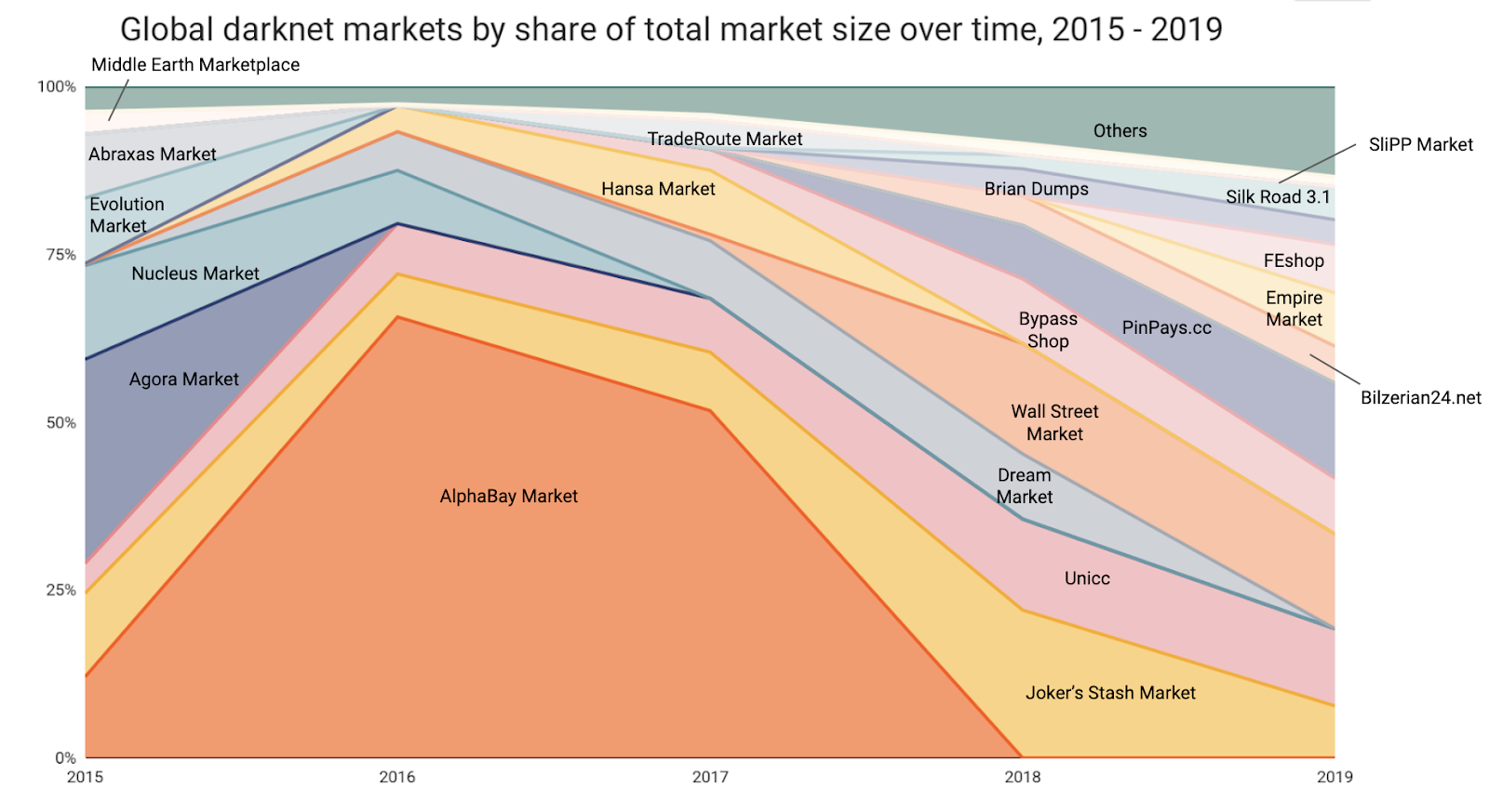

Above, we see how the top markets have shifted over time. Those focusing on drugs consistently remain the most popular. We should note though that some of the highest-earning markets shown above only serve specific countries or regions. For instance, Hydra Marketplace, by far the most popular market on the graph, caters only to customers in Russia. Below, we have another version of this chart showing only markets with a global customer base. Some of the markets shown in the second graph are more popular in some countries than others, but overall, the data shown below will be more relevant to investigators based in the U.S. and Western Europe.

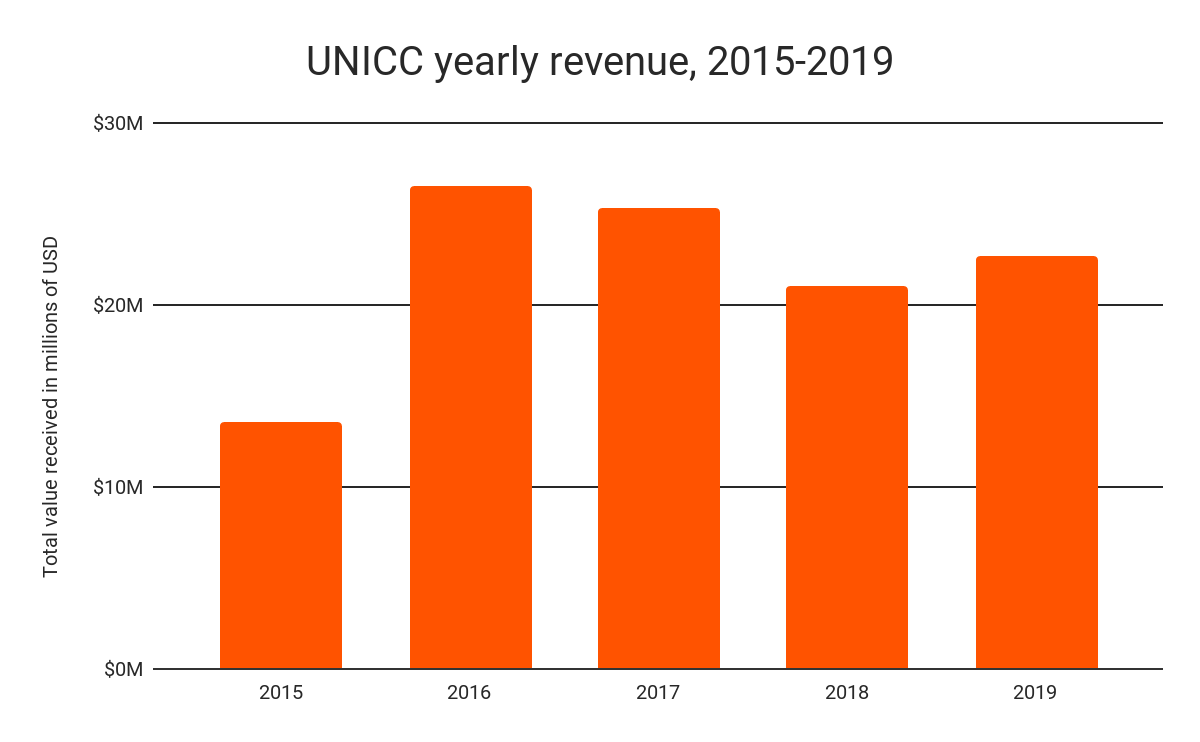

The dominance of drug-focused marketplaces holds here as well. However, it’s worth noting that markets specializing in other illicit goods also bring in sizable funds. Joker’s Stash Market and UNICC — two of the only markets to maintain steady popularity through the entire time period measured — are the best examples one popular market category known as card shops, which specialize in sales of stolen credit card information. We’ll examine card shop activity in greater detail later in this section.

Combatting online drug sales: Should law enforcement chase vendors or shut down markets?

For a long time, the strategy for law enforcement has been to go after the darknet markets themselves. On its face, this appears to be the most logical course of action — why go after individual vendors if you can take them all down in one fell swoop? Law enforcement agencies have achieved big wins following this strategy, shutting down once-prominent markets like AlphaBay and Hansa.

But, the problem with shutting down markets is that other ones fill the void extremely quickly. As of the end of 2019, there are at least 49 active darknet markets, so both users and vendors are spoilt for choice when seeking a new one. Not only that, but it’s easy for them to coordinate with one another to find new markets on forums such as Dread, a Reddit-like discussion site devoted to darknet markets.

We see an example of this in the shutdown of Nightmare Market earlier this year.

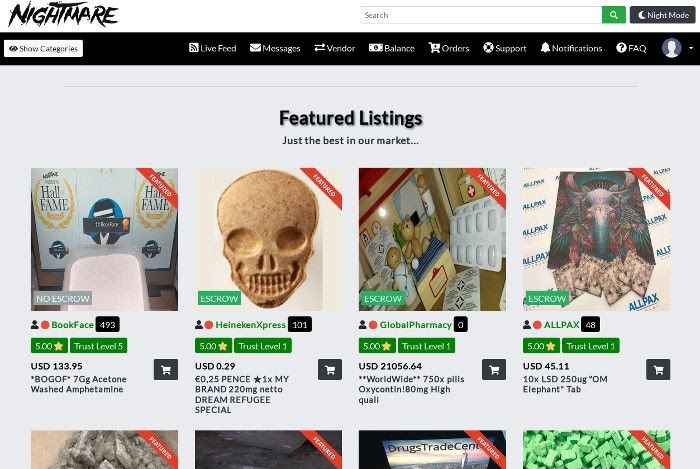

Nightmare market was a short-lived, moderately popular market that closed down in July 2019. Unlike other examples we’ve cited previously, Nightmare wasn’t shut down by law enforcement.

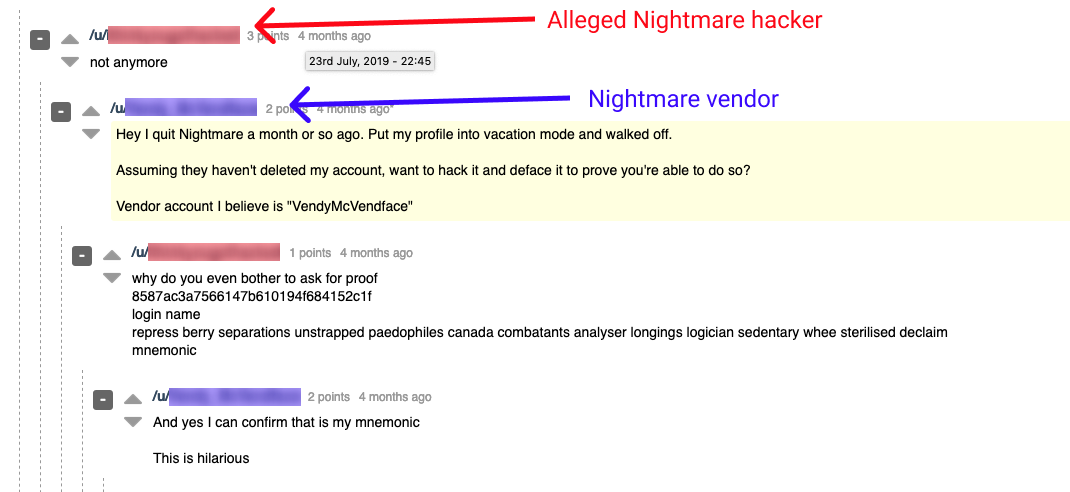

It’s unclear exactly what happened, but the shutdown was set in motion on July 23, when someone appearing to be a disgruntled former employee posted on Dread claiming to have hacked the site.

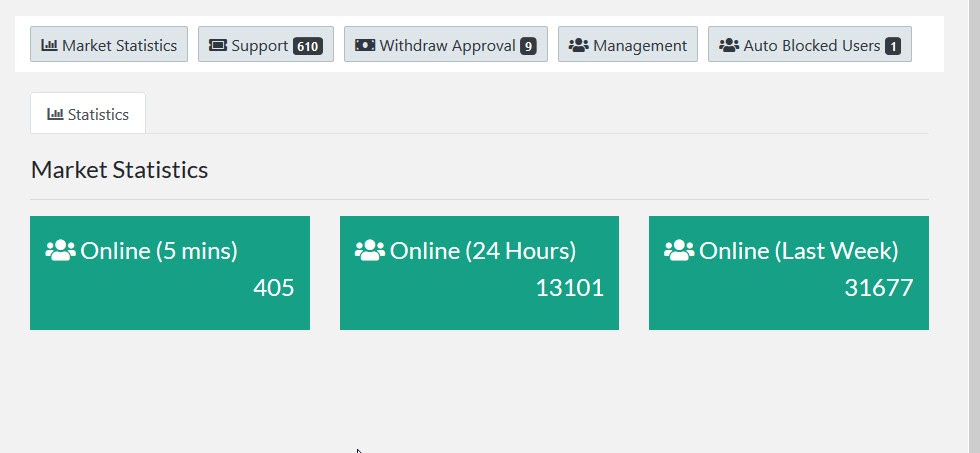

The hacking claim may be true, as the alleged rogue employee posted vendors’ mnemonic sequences — random series of words vendors could enter to recover their passwords — which several vendors then confirmed were correct. The hacker also posted screenshots of Nightmare’s backend, such as its user analytics and financial data.

It appears likely that Nightmare’s administrators decided to exit scam soon after the apparent hack. Customers were soon posting on Dread about which forums to move to next.

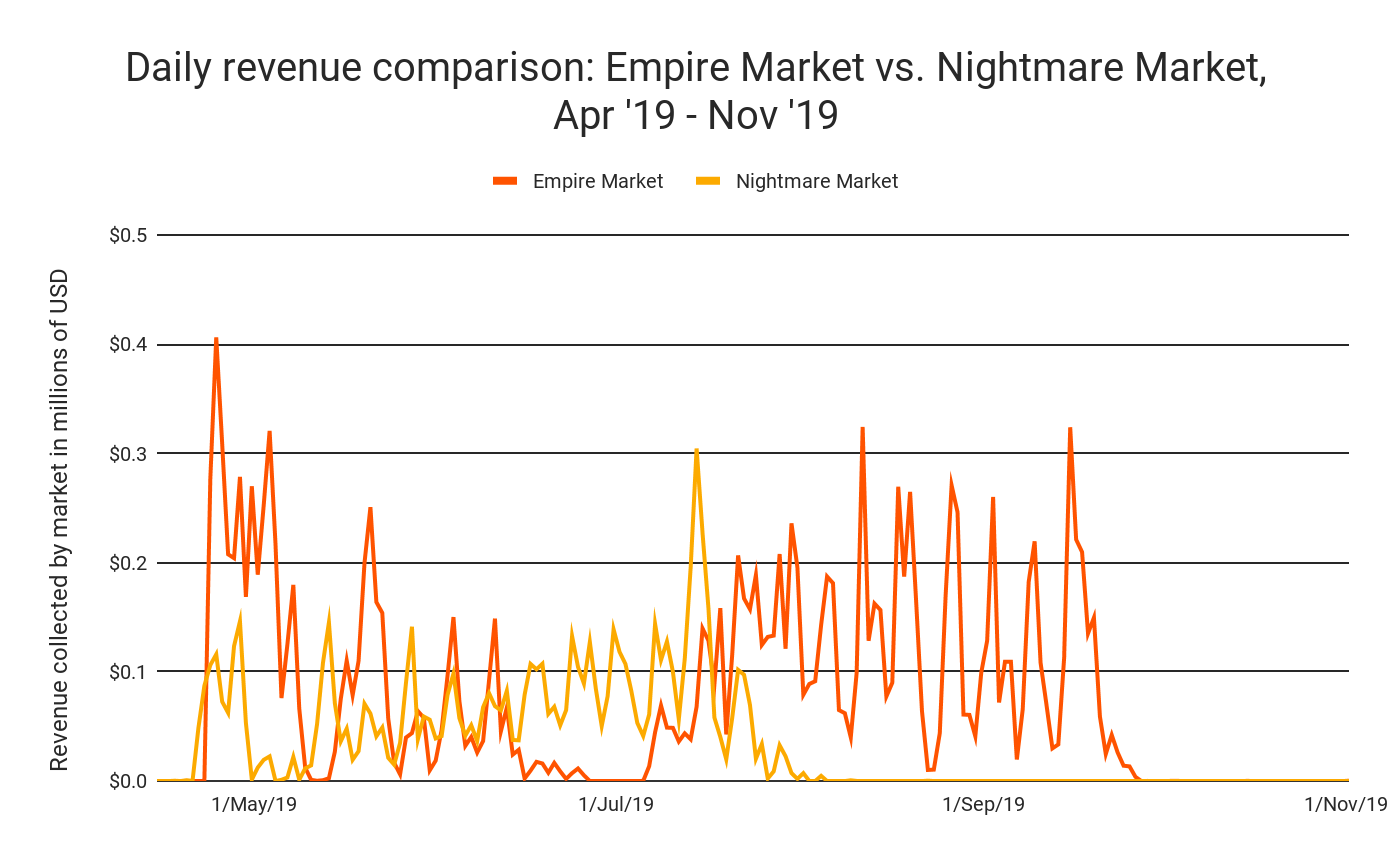

Sure enough, customers fled in droves. By the end of July, transactions on Nightmare ceased almost entirely. As the data below shows, Empire was able to pick up much of Nightmare’s former business, as its sales grew significantly just as Nightmare’s fell.

The Nightmare Market shutdown is a perfect microcosm of the issue with shutting down individual darknet markets. There are plenty of other markets out there, and it’s extremely easy for vendors to tell their biggest customers which one they’re moving to or are already active on.

That’s why many law enforcement agencies have shifted their focus to arresting individual vendors. Below is a case study of how this can be done. We caught up with Stefan Kalman, a Chainalysis user and drug enforcement officer in the Swedish Police Authority focused on darknet markets, and he walked us through a recent case of his involving a prominent darknet dealer active across multiple marketplaces.

Case study: How the Swedish Police Authority chased “Malvax” across markets

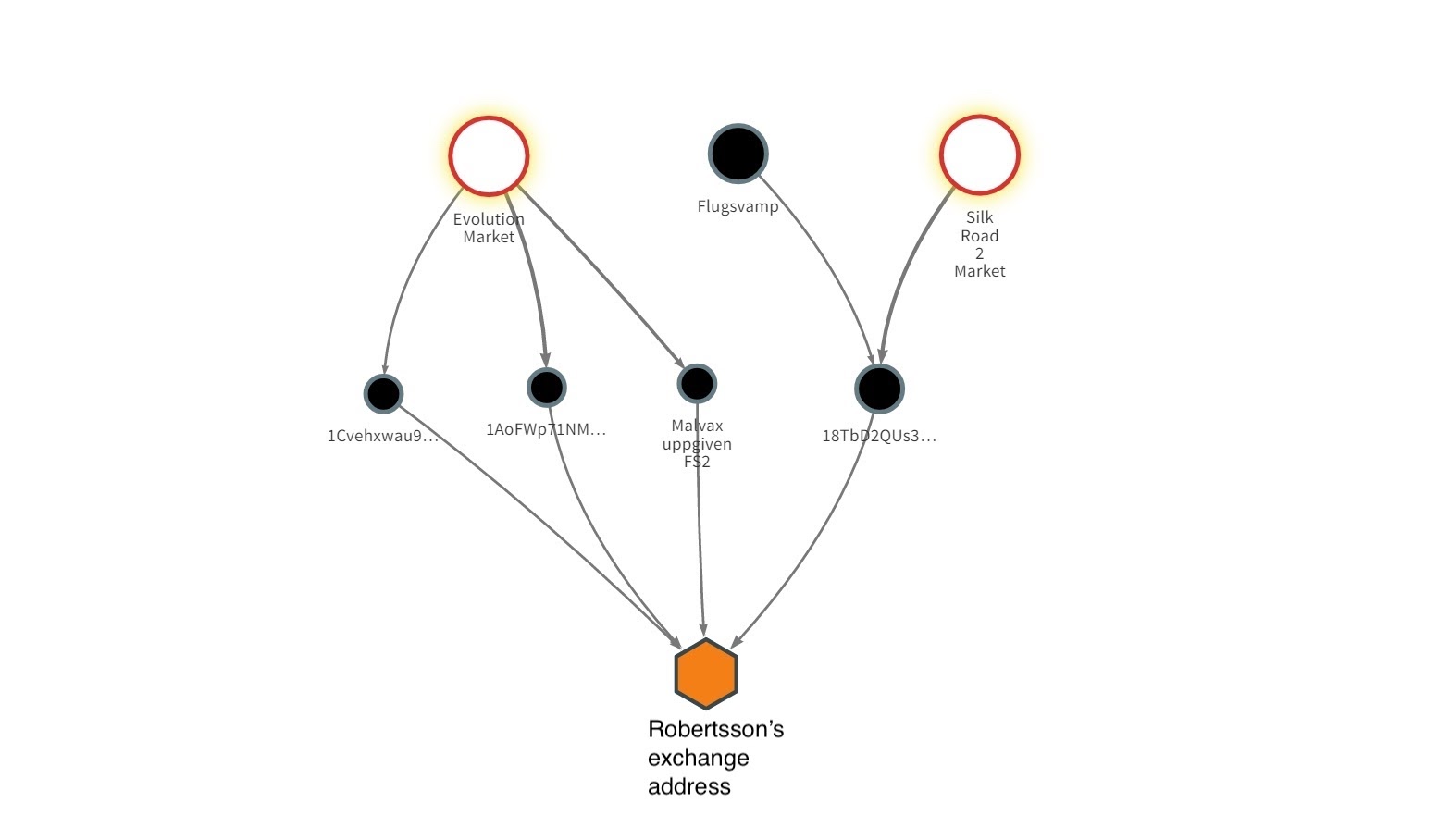

In 2014, Stefan Kalman and his team at the Swedish Police Authority became aware of a darknet market vendor active on both Silk Road 2.0 and Evolution, going by the handle Malvax. By observing his activity on the Silk Road forums, they were able to learn that he was also active on two other darknet markets: Evolution and Flugsvamp, a darknet market exclusive to Sweden, where he went by the handle Urbansgregor. Malvax had over 280 products for sale, including the dangerous synthetic opiate fentanyl.

While police had managed to seize some of his shipments to customers that were flagged by PostNord, Denmark’s main private mail carrier, they’d yet to uncover his real world identity. Malvax ran a sophisticated operation, relying on mixers and other obfuscation techniques to protect his identity. But police got a golden opportunity when they learned in mid-2015 that the FBI had seized the servers of Silk Road 2.0 after shutting it down the previous November. By reviewing the logs of those servers, they were able to get some of the Bitcoin addresses the dealer used under his Malvax alter ego, and used Chainalysis to trace some of them back to a regulated exchange headquartered in the UK.

Stefan and his team sent a subpoena to the exchange, which in turn provided them with enough information to figure out who Urbansgregor/Malvax really was: Fredrik Robertsson.

After conducting undercover purchases from Robertsson on Flugsvamp to confirm he was still selling drugs, Stefan and his team received warrants to tap Robertsson’s phone, put a GPS tracker on his vehicle, and watch his house with cameras. By placing more test orders with him and observing his online and offline behavior, they were able to intercept more of his packages and build their case further.

Eventually, they got a search warrant for Robertsson’s house, raided it, and found drugs. In addition, they found debit cards issued by a Hong Kong-based cryptocurrency exchange, which he could use to withdraw fiat currency from ATMs in Sweden. After cracking his encrypted email account, the agents found over 1900 invoices for drug orders, as well as messages confirming that Robertsson’s brother, a Bitcoin and cybersecurity expert based in Asia, was also in on the scheme. Stefan and his team confirmed this finding by using to Chainalysis to trace some of the brother’s Bitcoin withdrawals in Hong Kong and Thailand.

Thanks to the evidence Stefan and his team gathered on the Robertsson brothers, Swedish courts were able to convict them of selling drugs on the darknet.

Card shop deep dive

As we mentioned previously, while shops specializing in drugs are the most popular type of darknet market, they’re not the only type of darknet market to achieve consistent sales. Below, we’ll look at another popular type of market.

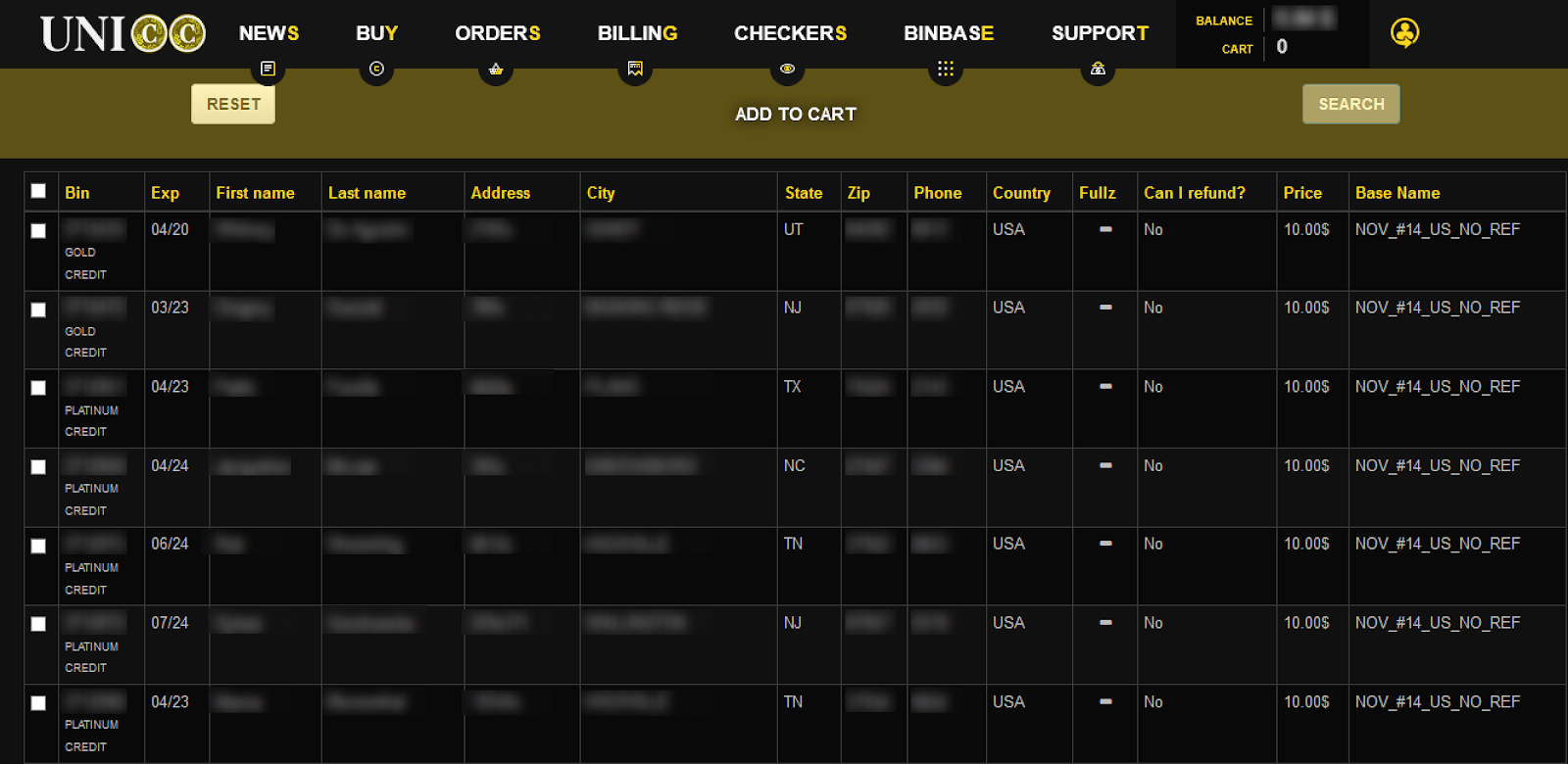

You’ve probably heard of big security breaches at companies like Capital One and Home Depot, in which tens of millions of customers’ credit card information was compromised. Ever wonder where that stolen information ends up?[1][2] There’s a good chance it’s available on card shops. Card shops are a category of darknet market where users can purchase stolen credit card information. We’ll look at UNICC as an example.

Above, we see some of UNICC credit card listings. Cards go for anywhere from $2 to $15, with the average sitting at about $10. The exact price depends on a few different factors. One is area of origin. U.S. and western Europe-based cards typically fetch a premium. Another influence on price is the amount of the cardholder’s personally identifiable information (PII) that comes with the card, such as street address and phone number. Most reputable online stores ask for this information upon purchase, hence why having it drives up the card price.

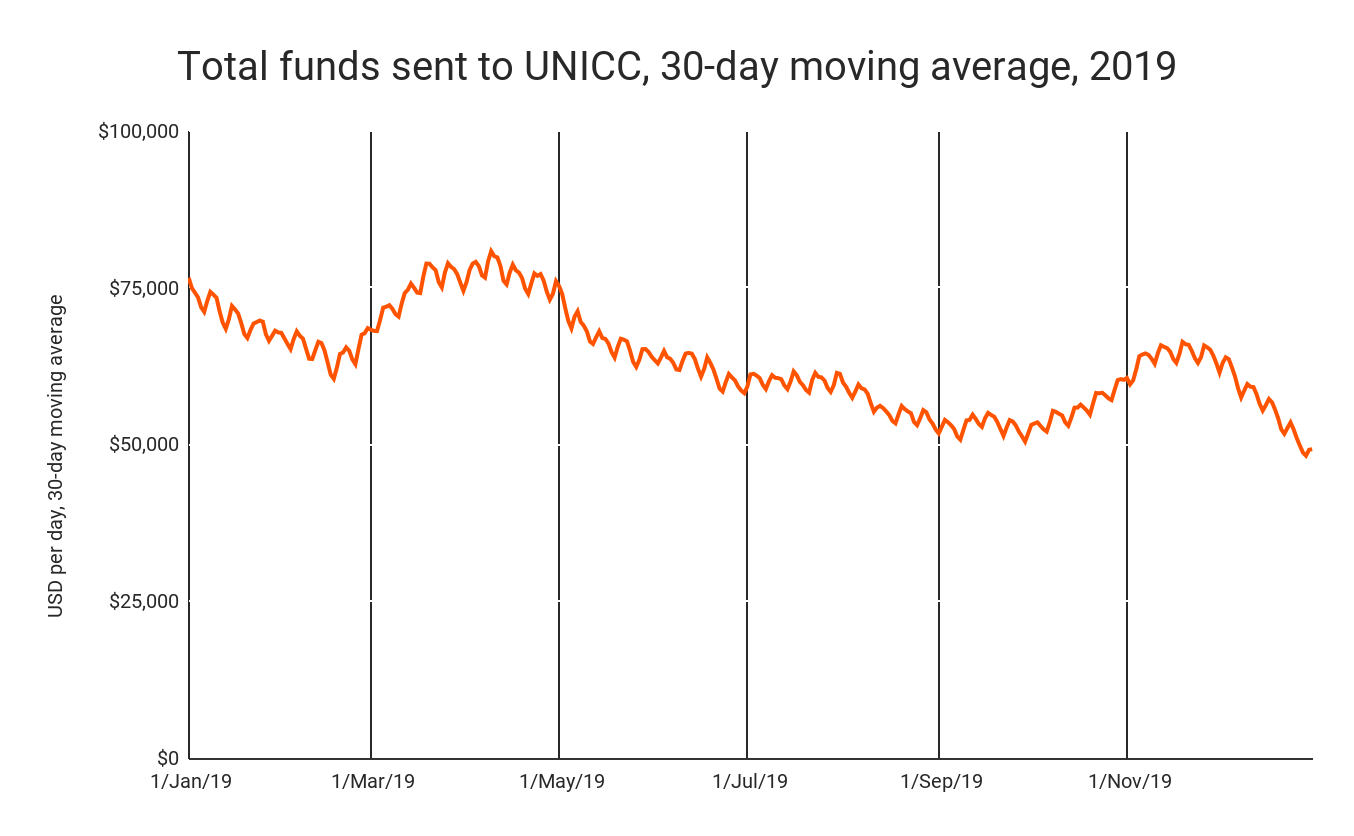

UNICC took in at least $22.7 million worth of cryptocurrency in 2019, making it the fourth most active market last year. Activity remained relatively steady over the course of the year, peaking in April. Based on that total sales figure and estimating an average cost of $10 per card, we estimate that UNICC sold card data belonging to nearly 3 million customers.

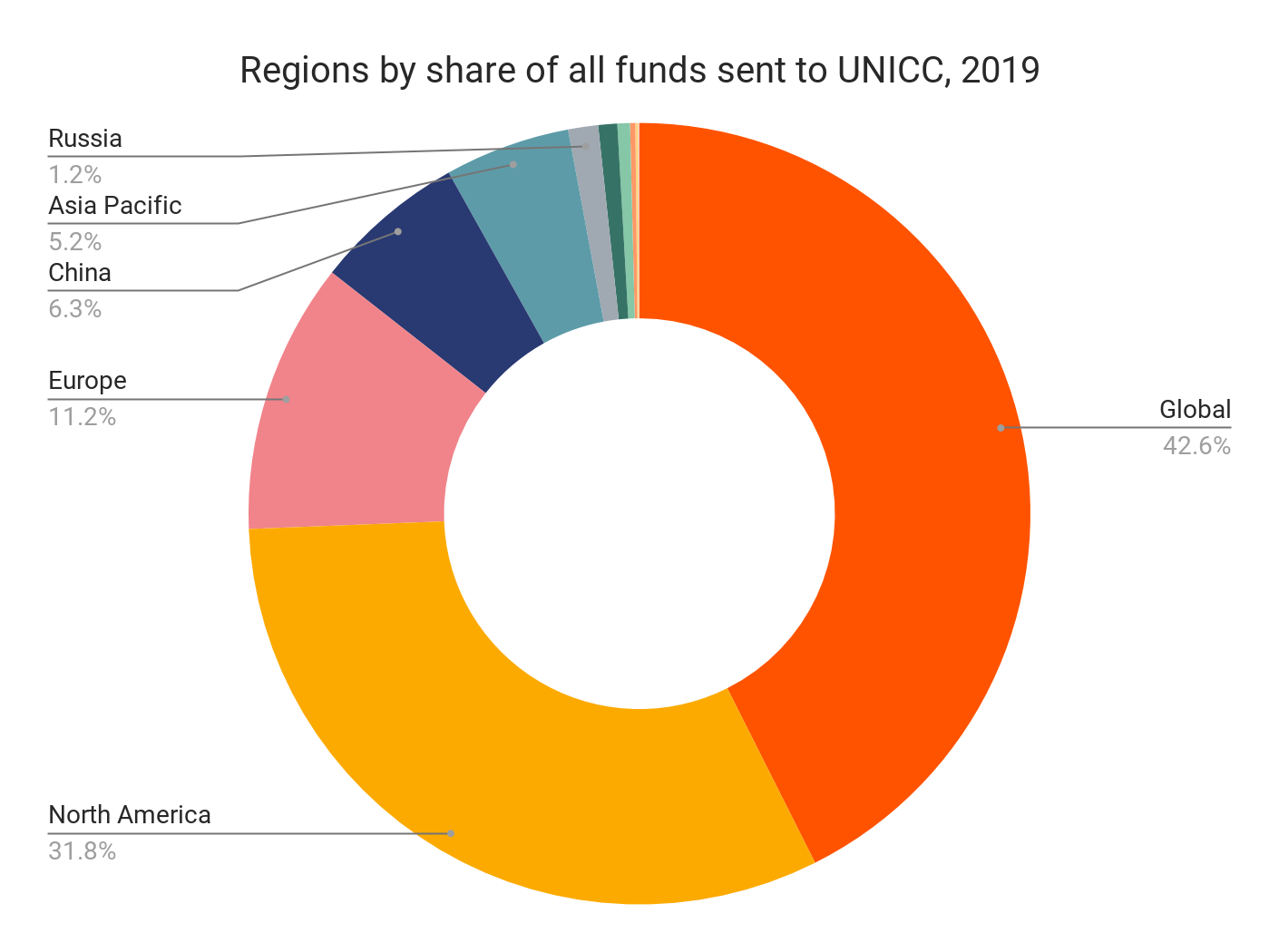

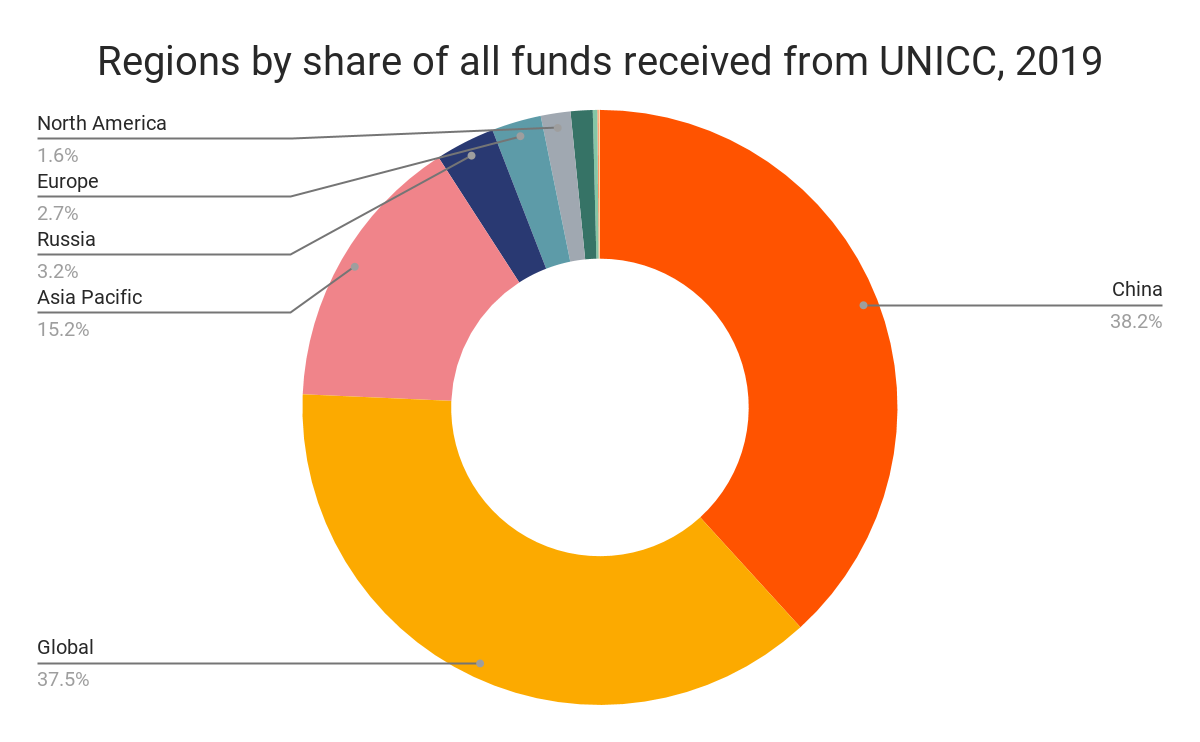

Our regional data reveals that most people buying stolen credit card data on UNICC are from North America (after Global), while most of those selling it are from China. While it’s difficult to say exactly why that is, it’s possible that more criminals from China have the technological proficiency to steal credit card data.

What comes next for darknet markets?

Some darknet markets have begun implementing user safety features that make it more difficult for them to be scammed by vendors or by the market itself. For instance, many have adopted multi-signature technology, meaning that both vendor and buyer have to confirm an order has been completed for funds to move. This way, buyers can approve their funds to move only when they’ve received their order. Another such feature is wallet-less escrow, also known as direct deposit. Wallet-less escrow makes it impossible for markets to exit scam users by removing the need for them to deposit funds to a wallet controlled by the market. Instead, they receive a new disposable wallet for every order they place, and the cryptocurrency they deposit goes straight to the vendor — the market itself never actually controls it. Cryptonia was an active market that incorporated both multi-signature transactions and wallet-less escrow, though it recently closed down voluntarily.

Some darknet markets are also adopting new infrastructures to avoid shutdowns by law enforcement. OpenBazaar, for instance, has a fully decentralized structure, similar to the blockchain itself or the Tor web browser, that would make it impossible to take down. Users simply download and run a program that allows them to connect directly, rather than through a website. Particl.io offers a similar marketplace with its own coin and wallet infrastructure. Neither of these markets have achieved widespread adoption yet. OpenBazaar, for instance, only has between 10 and 20 vendors with substantial traction, while the most popular markets have hundreds. Anecdotally, we believe the low adoption is because OpenBazaar and Particl.io are harder to use than standard darknet markets, but both would present new challenges to law enforcement if they gained popularity.

Finally, we may see more darknet markets accept, or perhaps even mandate the usage of privacy coins like Monero. Monero uses an obfuscated public ledger to make it more difficult to see the senders, receivers, or amounts of cryptocurrency exchanged on transactions. As of now, Empire appears to be the only major darknet market accepting Monero, but that could change in 2020.

This blog is an excerpt from the Chainalysis 2020 Crypto Crime Report. Click here to download the full document!