We’ve written in the past about how money laundering activity is highly concentrated to just a few services, and within those services, concentrated even further to a small number of deposit addresses. That remained true in 2022, though as we’ll explore, with a few new wrinkles. In addition, we’ll examine the rise of underground money laundering services that exist separately from the crypto businesses most are familiar with, and also analyze funds still held by crypto criminals on the blockchain.

In this report, we cover:

- 2022 crypto money laundering activity summarized

- Overall mixer usage falls in 2022, but illicit usage hits all-time high

- Money laundering concentration at fiat off-ramps

- Underground money laundering services are a growing concern

- Criminal balances dropped in 2022

2022 crypto money laundering activity summarized

Money laundering in cryptocurrency typically involves two types of on-chain entities and services:

- Intermediary services and wallets: These can include personal wallets (also known as unhosted wallets), mixers, darknet markets, and other services both legitimate and illicit. Crypto criminals typically use these services to hold funds temporarily, obfuscate their movements of funds, or swap between assets. DeFi protocols are also used by illicit actors in order to convert funds but, as we will discuss, are not an efficient means of obfuscating the flow of funds.

- Fiat off-ramps: This refers to services that allow for cryptocurrency to be exchanged for fiat. This is the most important part of the money laundering process, as the funds can no longer be traced via blockchain analysis once they hit a service — only the service itself would have visibility into where they go next. Additionally, if the funds are converted into cash, they can only be followed further through traditional financial investigation methods. Most fiat off-ramps are centralized exchanges, but P2P exchanges and other services can also serve this function.

With that in mind, let’s look at some of the money laundering trends we saw in 2022.

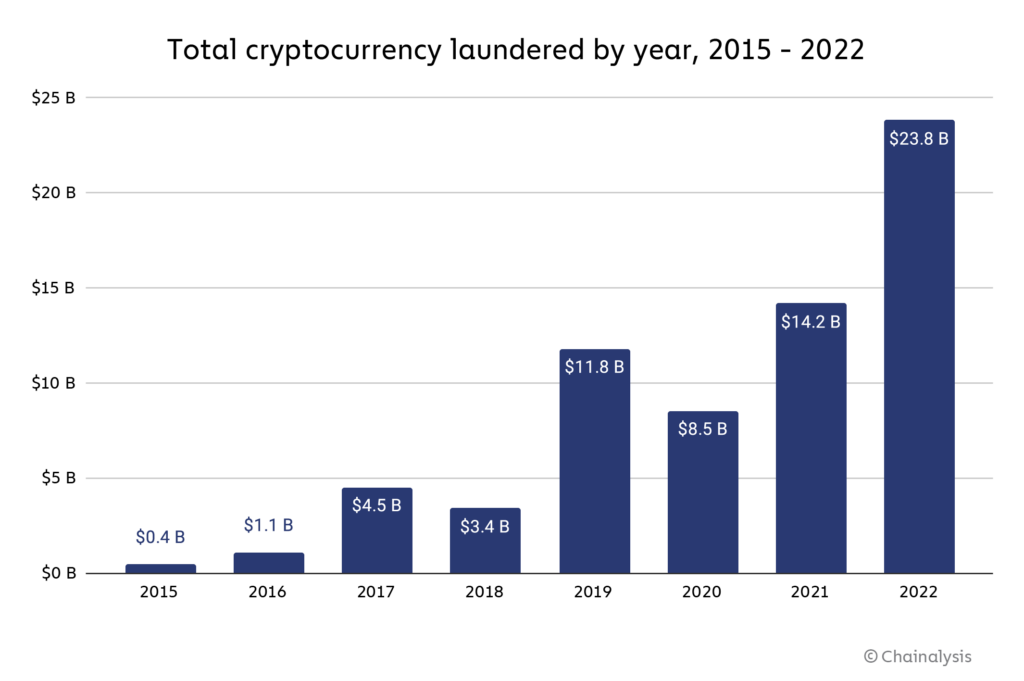

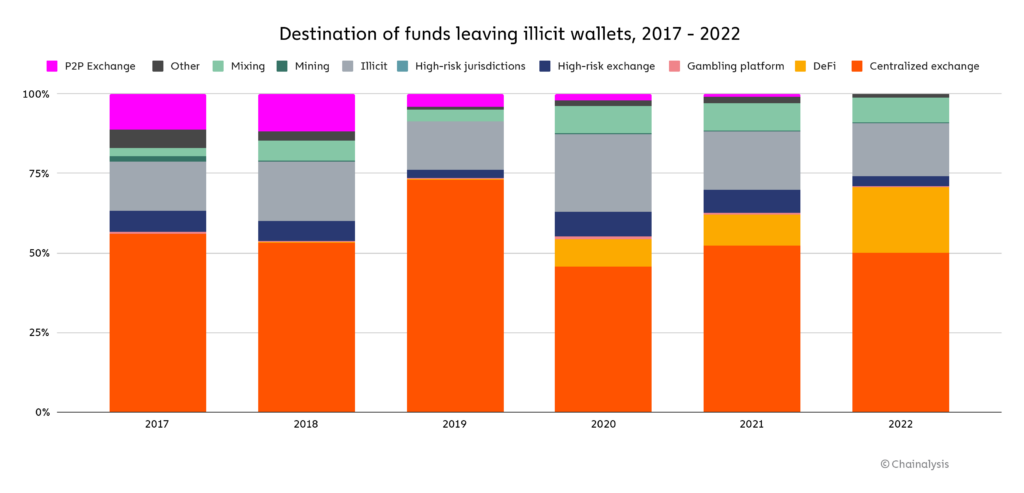

Overall, illicit addresses sent nearly $23.8 billion worth of cryptocurrency in 2022, a 68.0% increase over 2021. As is usually the case, mainstream centralized exchanges were the biggest recipient of illicit cryptocurrency, taking in just under half of all funds sent from illicit addresses. That’s notable not just because those crypto exchanges generally have compliance measures in place to report this suspicious activity and take action against the users in question, but also because those exchanges are fiat off-ramps, where the illicit cryptocurrency can be converted into cash.

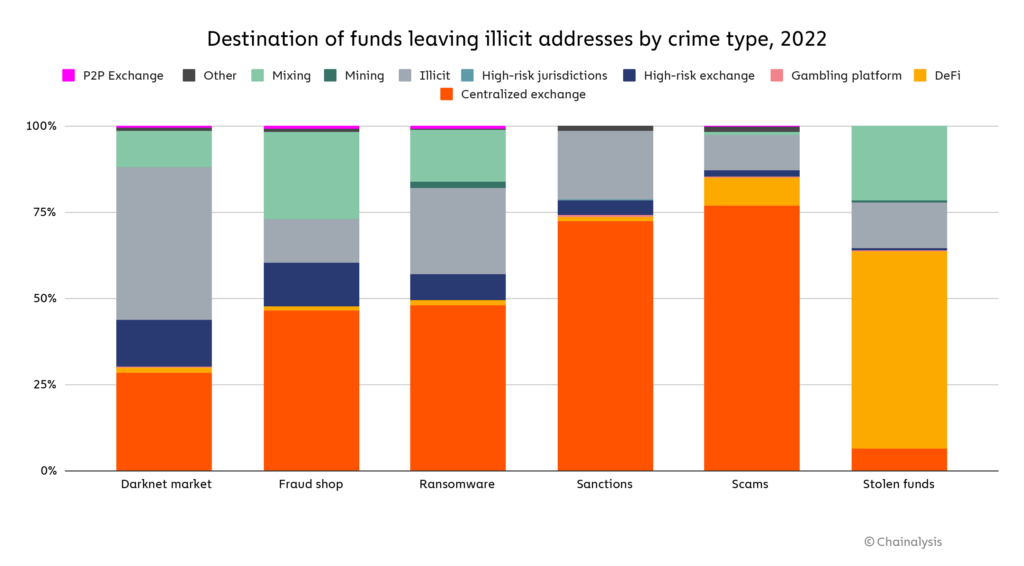

More illicit funds were sent to DeFi protocols than ever before, a continuation of a trend that began in 2020. Cybercriminals send funds to DeFi protocols not because DeFi is useful for obscuring the flow of funds. In fact, quite the opposite is true, as unlike with centralized services, all activity is recorded on-chain. Keep in mind too that DeFi protocols don’t allow for the conversion of cryptocurrency into fiat, so most of those funds likely moved next to other services, including fiat off-ramps. And as we see below, almost all usage of DeFi protocols for money laundering is carried out by one criminal group of hackers stealing cryptocurrency.

Hackers holding stolen cryptocurrency are the only criminal category sending the majority of funds to DeFi protocols, at a whopping 57.0%. 2022 was an enormous year for hacking, hence why these cybercriminals were almost single-handedly able to drive the overall increase in the usage of DeFi protocols for money laundering. The fact that DeFi protocols themselves were the biggest target of hacks in 2022 also influences these numbers. In DeFi hacks, attackers often end up with tokens that aren’t listed on other exchanges, so they need to use decentralized exchanges (DEXes) to swap them for more liquid crypto assets. DEXes have historically been used to convert funds to Ether, which can then be sent to Ethereum-based mixers. DEXes have also been used to convert to virtual assets that will be more likely to hold their value, or in the case of stablecoins, to swap to an asset that cannot be frozen by the stablecoin issuer. However, as noted previously, DEXes don’t enable the conversion of funds from virtual currency to fiat currency — this must still be done through a centralized exchange or other fiat off-ramp.

Aside from hackers, crypto criminals send the majority of their funds directly to centralized exchanges, but there are some notable exceptions. For instance, darknet market vendors and administrators send most of their funds to other illicit services — primarily other darknet markets, some of whom may offer money laundering services similar to those of the now-shuttered Hydra Market. Darknet market addresses also sent a large share of funds to high-risk exchanges, such as Bitzlato, a Russia-based exchange shut down in an international law enforcement action recently for its money laundering activity. Ransomware attackers are another interesting case. Addresses associated with them send a disproportionately large share of funds to mixers, and also make heavy use of illicit services. Fraud shop vendors and administrators are also notable for their outsized mixer usage.

In total, we see that over half of funds sent from illicit addresses travel directly to centralized exchanges, both mainstream and high-risk, where they can be exchanged for fiat unless compliance teams take action. However, over 40% of illicit funds move first to intermediary services — primarily mixers and illicit services or DeFi protocols —, with most of those funds coming from ransomware, darknet market, and hacker addresses.

Overall mixer usage falls in 2022, but illicit usage hits all-time high

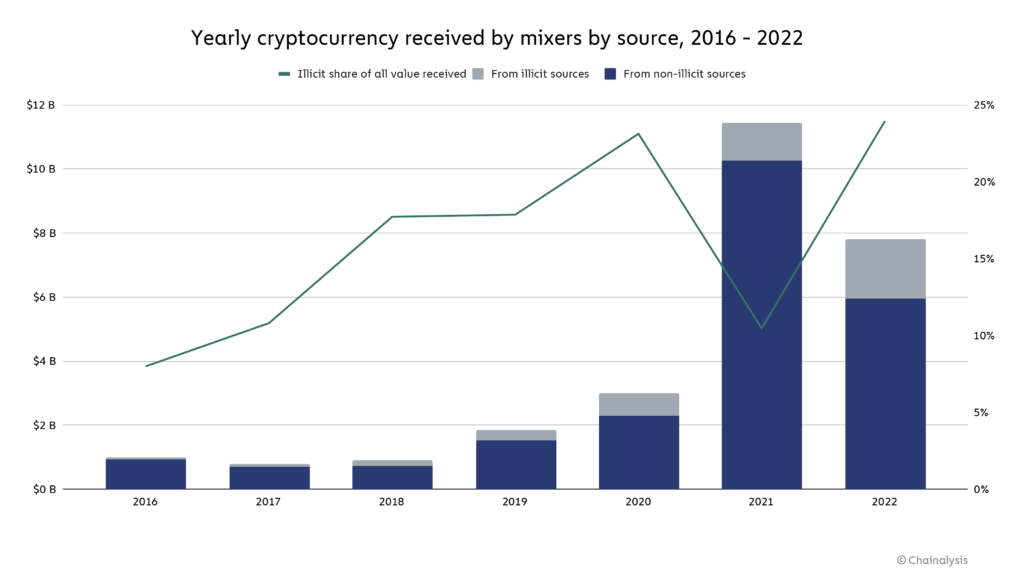

Crypto mixers are a popular obfuscation service used by crypto criminals, taking in 8.0% of all funds sent from illicit addresses in 2022. Mixers function by taking in cryptocurrency from multiple users, mixing it all together, and sending each user an amount equivalent to what they put in. The result is that each user’s cryptocurrency can now only be traced back to the mixer, rather than to its original source, unless special blockchain analysis techniques are employed. You can learn more about how different types of mixers work here.

There are many legitimate use cases for mixers, most of which are related to financial privacy. For example, if someone knows your cryptocurrency address, they can see virtually your entire transaction history on the blockchain, so it’s reasonable for users to try and prevent this with mixers. Of course, the financial privacy provided by mixers is also valuable to criminals, hence their popularity as a destination for illicit funds. In May 2022, OFAC sanctioned a mixer for the first time ever when it designated Blender.io for its role in laundering cryptocurrency stolen by North Korean hacking syndicate Lazarus Group. OFAC didn’t waste any time designating its second mixer, Tornado Cash, in August for the same reasons.

The sanctioning of prominent mixers may have contributed to two trends we observed in 2022: The total amount of cryptocurrency sent to mixers fell significantly, and the funds that did travel to mixers were more likely to come from illicit sources.

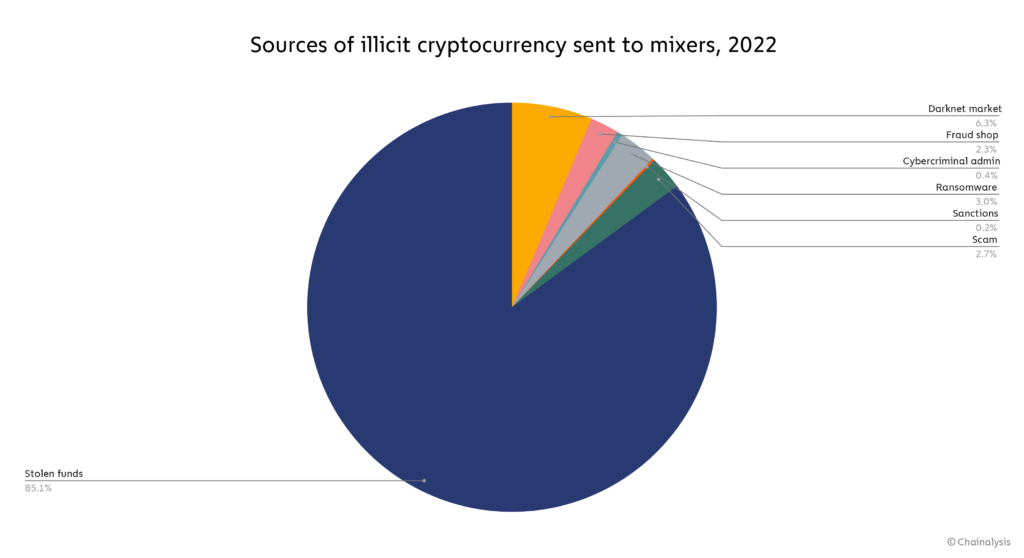

Mixers processed a total of $7.8 billion in 2022, 24% of which came from illicit addresses, whereas in 2021, they processed $11.5 billion, only 10% of which came from illicit addresses. The data suggests that legitimate users have decreased their use of cryptocurrency mixers, possibly due to law enforcement actions against prominent ones, while criminals have continued to use them. It’s also worth noting that the vast majority of illicit value processed by mixers is made up of stolen funds, the majority of which were stolen by North Korea-linked hackers, who are unlikely to be dissuaded by the threat of U.S. sanctions given they reside in a non-cooperative jurisdiction.

Other sanctioned entities and darknet markets also accounted for significant shares of value received by mixers in 2022.

Money laundering concentration at fiat off-ramps

As we discussed above, fiat off-ramp services like exchanges are crucial for money laundering, as those are the services where criminals can turn crypto into cash, which is likely their ultimate goal. Fiat off-ramps are also among the most heavily regulated cryptocurrency services, and their compliance teams have an important role to play in flagging incoming illicit funds and preventing them from being exchanged for cash. But while there are thousands of cryptocurrency services offering fiat off-ramping, a select few receive most of the illicit funds we observe on-chain.

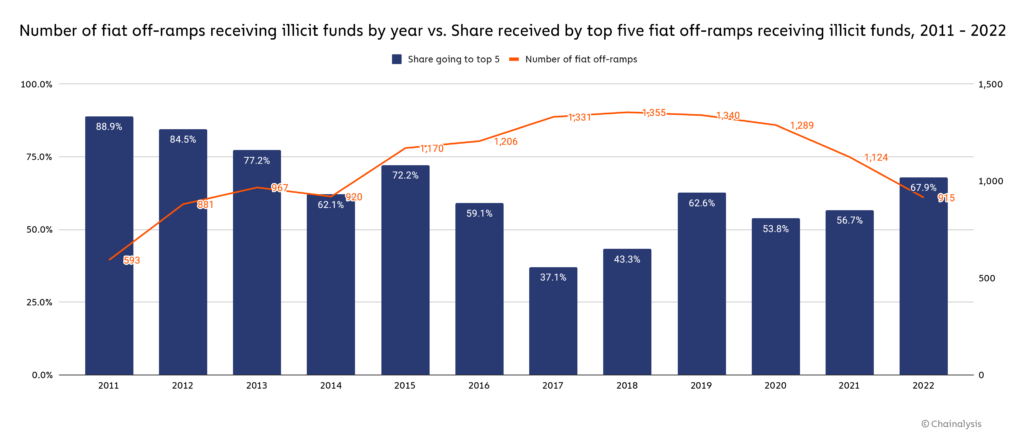

915 unique fiat off-ramping services received illicit cryptocurrency in 2022, down from 1,124 in 2021. Some of that dropoff is likely due to exchanges going out of business during the bear market. Of the illicit funds received by exchanges, 67.9% went to just five services, all of which are centralized exchanges. This represents an increased concentration compared to 2021, when the top five services received only 56.7% of illicit funds.

But what about the individual exchange users facilitating this activity? We can assume that many of the criminals sending funds to fiat off-ramps are using an account at the service that they themselves control. But in some cases, criminals work with specialized money laundering service providers, who control the accounts and help criminals convert their cryptocurrency into cash once it arrives at the exchange. Those businesses fall into the category of nested services, meaning services that are built on top of larger exchanges, using those exchanges’ deposit addresses to access their liquidity and trading pairs. Most nested services are legitimate businesses — many prominent over-the-counter (OTC) brokers, for instance, operate as nested services. However, on-chain data suggests that a small group of nested services facilitate the majority of money laundering, either due to negligence or purposeful catering to crypto criminals.

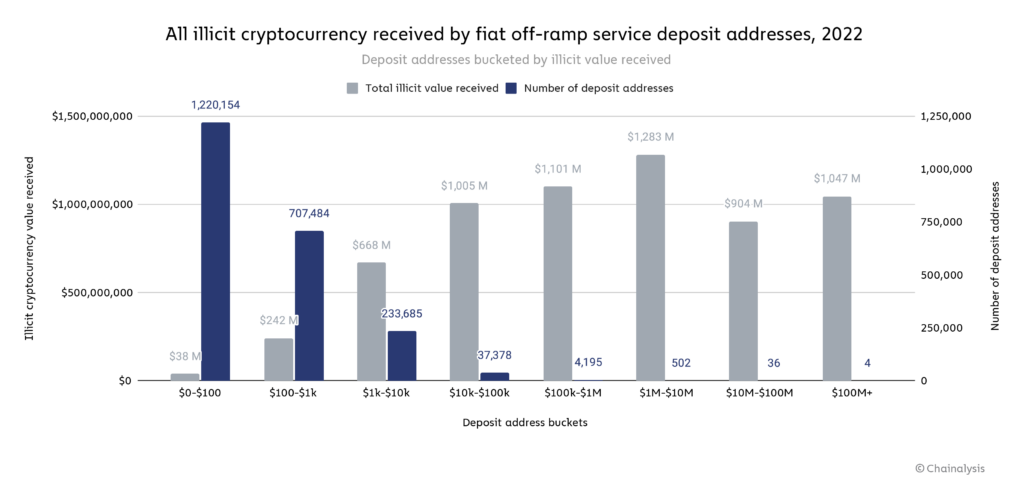

For that reason, it’s useful to analyze the specific service deposit addresses that account for the majority of money laundering activity, as we can generally attribute the activity of a given deposit address to a user at the service whose account is linked to that deposit address. In the graph below, we look at all off-ramp service deposit addresses that received any illicit funds in 2022, bucketed by the range in value of illicit funds received.

The graph shows that most cryptocurrency money laundering is facilitated by a very small group of people. Four deposit addresses cracked $100 million in illicit cryptocurrency received in 2022, and combined received just over $1.0 billion, while the 1.2 million deposit addresses receiving under $100 in illicit funds account for $38 million in total. Further, 51% of the $6.3 billion in illicit funds received by fiat off-ramp services in 2022 went to a group of just 542 deposit addresses. Those numbers represent a lower level of money laundering concentration at the deposit address level than we saw in 2021, even though 2022 saw a slight uptick in concentration at the service level. One possible reason for this is that continued law enforcement crackdowns against crypto money launderers, such as the shutdown of the exchange Bitzlato, have spooked the biggest money laundering service providers, or encouraged them to spread their operations across more deposit addresses.

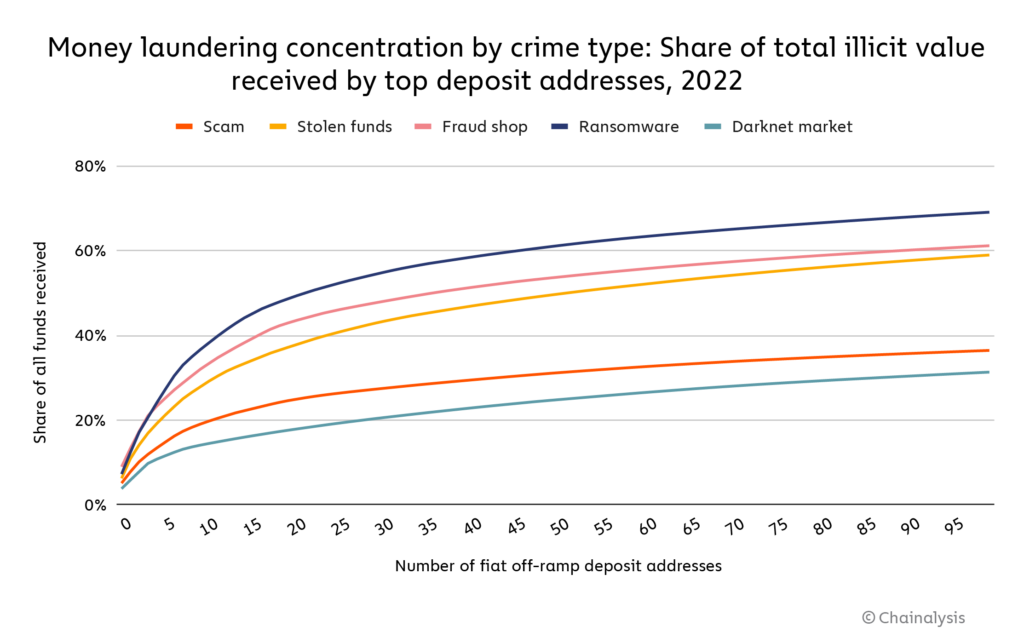

We also see high variance in the degree of money laundering concentration by crime type.

Just 21 deposit addresses account for 50% of all funds sent from ransomware to fiat off-ramps, while the top 21 deposit addresses for funds received from darknet markets account for just 18%.

Despite the drop in overall concentration, 51% of illicit funds moving to just 542 deposit addresses at 83 exchanges still represents a high level of money laundering concentration. If law enforcement and compliance teams were able to disrupt the individuals and groups behind those addresses, it would be much more difficult for criminals to launder cryptocurrency at scale, and go a long way toward making the ecosystem safer.

Underground money laundering services are a growing concern

Another money laundering trend we’ve observed is the growth of underground services that aren’t as publicly accessible or well-known as standard mixers, as they are typically accessible only through private messaging apps or the Tor browser, and usually only advertised on darknet forums.

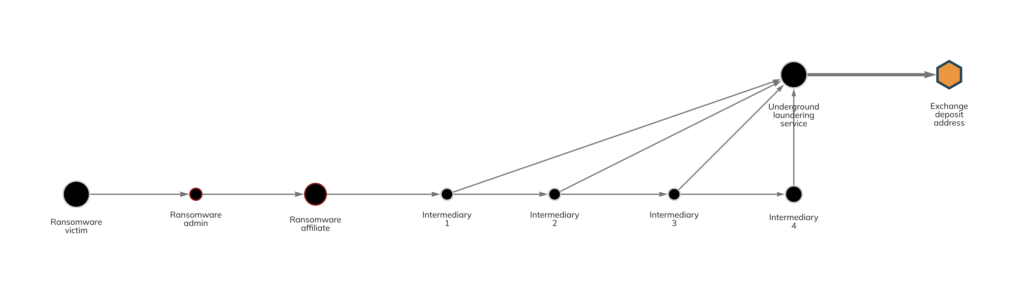

We’ve written in past Crypto Crime reports about OTC brokers nested on exchanges that launder large quantities of illicit funds – many of which seem to explicitly cater to cybercriminals. While this activity still exists, we’re also seeing the rise of services with brand names and custom infrastructure, which vary in terms of complexity. Some function simply as networks of private wallets, while others are more akin to an instant exchanger or mixer. But generally, what links them is that they typically move cryptocurrency to exchanges on behalf of cybercriminals, exchange them for either fiat currency or clean crypto, then send that back to the cybercriminals. Like the nested OTC services, many of these underground services also use those exchanges for liquidity. We can see one example on the Chainalysis Reactor graph below, though names of relevant illicit organizations have been redacted due to ongoing investigations.

In this case, the underground laundering service, which functions similarly to a mixer, helped an affiliate for a prominent ransomware strain move funds to a deposit address at a large, centralized exchange. The deposit address is believed to be controlled by the laundering service itself.

Analysis of underground laundering activity like that shown above isn’t as easy to spot as most activity on public blockchains is by default — identifying these services’ addresses requires extensive investigative work, and untangling their transactions requires advanced blockchain analysis techniques such as demixing. That means it’s difficult to analyze these services’ activity at scale. However, we can estimate their activity by analyzing the activity of all wallets and networks of wallets that meet the following criteria:

-

-

-

-

- Receive large amounts of cryptocurrency from illicit services

- Send large amounts of cryptocurrency to exchanges and other fiat off-ramps

-

-

-

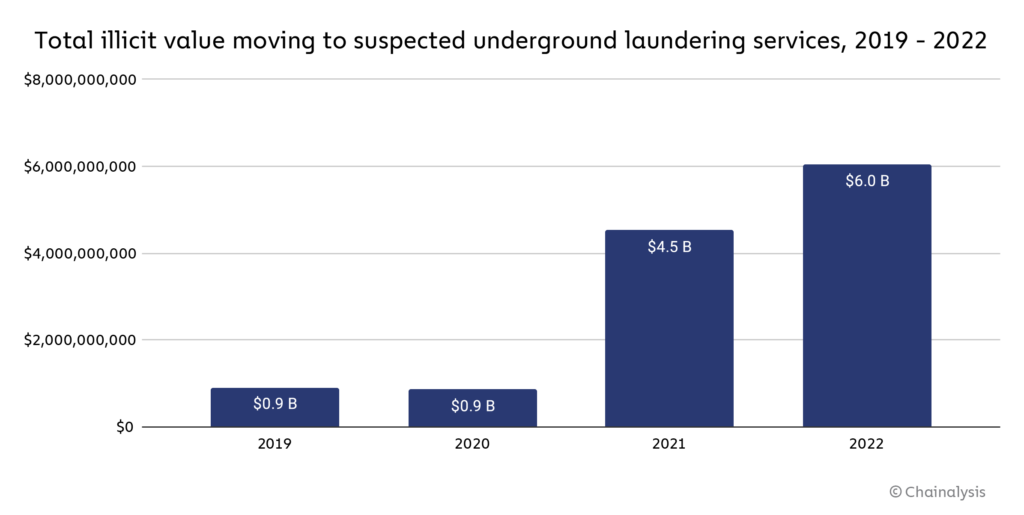

The graph below shows the yearly cryptocurrency value received by wallets that fit those criteria.

Total cryptocurrency moving to wallets fitting those criteria has grown over the last few years, and hit $6 billion in 2022. Again, these are estimates — we can’t guarantee that all of the wallets included in this analysis are necessarily underground laundering services, but their on-chain activity suggests that they could be. It’s also possible that usage of underground money laundering services will pick up as high-risk exchanges, which have facilitated this activity in the past, face increased pressure from law enforcement, as we saw with Garantex and Bitzlato.

Criminal balances dropped in 2022

As we mentioned previously, criminals will often leave funds in a personal wallet, or in a wallet associated with a criminal service for extended periods of time. In some cases, this may be because their crimes have generated enough attention that they don’t feel it’s possible to move the funds without investigators or crypto industry observers calling it out — we see this often with funds stolen in hacks. In other cases, this may reflect an intention to hold cryptocurrency in the expectation its price will rise, or to continue using it for other criminal endeavors. Thanks to the transparency of the blockchain, we can track these criminal balances granularly to know how much confirmed illicit entities are holding at any given time. Below, we’ll take a look at how criminal balances changed in 2022.

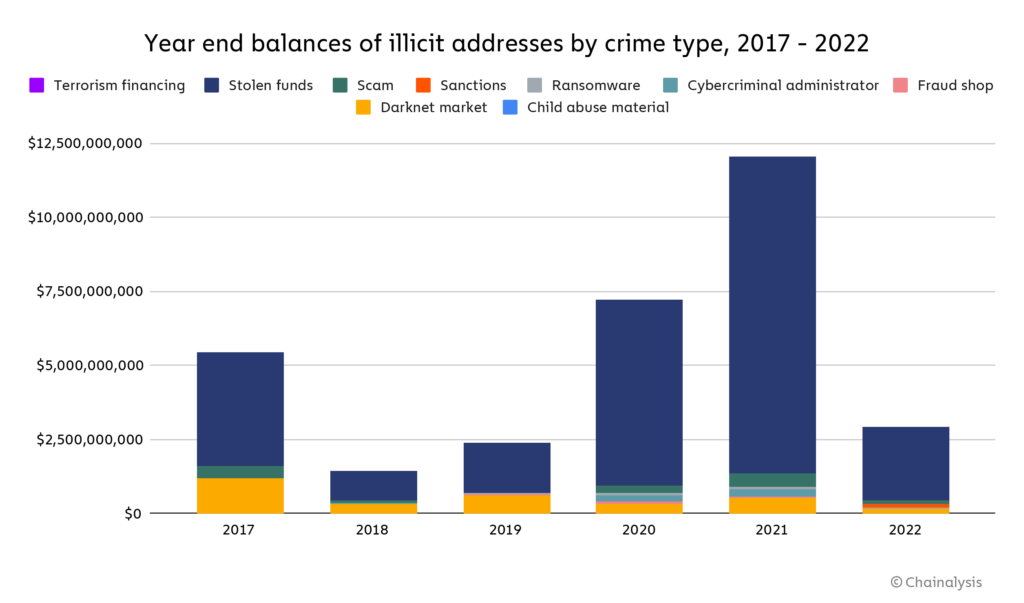

Two things stand out: The first is that criminal balances have plummeted in value in 2022, from $12 billion at the end of 2021 to just $2.9 billion. Price declines in the ongoing bear market and large, successful seizures by law enforcement in 2022 are the most likely causes of this.

Second, we can see that stolen funds dominate on-chain criminal balances. This is likely due to the fact that the amount of cryptocurrency stolen in hacks has skyrocketed over the last two years, and that these hacks often become huge points of discussion on crypto Twitter and in other industry forums, with many tracking the funds publicly and sharing the addresses holding stolen funds. This can make it difficult for hackers to move stolen funds to a fiat off-ramp, which could be one reason they choose to leave the funds sitting in personal wallets.

Criminal balances are valuable to track as they represent a lower-bound estimate of cryptocurrency that could potentially be seized by law enforcement — the true number for criminal balances is likely much higher, as it includes funds associated with addresses we’ve yet to attribute to criminal entities and funds derived from offline criminal activity and converted to cryptocurrency after the fact.

Investigative agencies have continued to ramp up their ability to seize cryptocurrency in 2022, with the IRS Criminal Investigation Unit announcing they seized $7 billion worth of digital assets last year, more than double the amount seized in 2021. 2022 saw several other notable stories of cryptocurrency seized from criminals, including:

-

-

-

-

- A record $3.6 billion seized from two individuals accused of laundering funds stolen in the 2016 hack of Bitfinex

- The November 2021 seizure of $3.36 billion in Bitcoin stolen from darknet market Silk Road, which was later announced publicly in November 2022

- The seizure of $30 million worth of cryptocurrency stolen from Axie Infinity’s Ronin Bridge, marking the first successful seizure of cryptocurrency stolen by North Korean hacking syndicate Lazarus Group

-

-

-

Our data on criminal balances suggests there are still more opportunities for successful seizures, and more generally, illustrates a crucial difference between financial investigations in cryptocurrency versus fiat: In cryptocurrency, criminal holdings can’t be stashed away in opaque networks of banks and shell corporations — almost everything is out in the open.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.