[FEBRUARY 13, 2025 UPDATE]: Some numbers in this analysis have been adjusted to correct for an error.

In last year’s report, we introduced a novel methodology for detecting suspicious trading patterns in crypto markets by analyzing on-chain data. We focused on decentralized finance (DeFi), given its transparency and the availability of on-chain information, which is not similarly available in centralized trading platforms. Our approach tracks patterns of behavior and not intent, which means that it is not by itself sufficient to prove market manipulation; however, it provides a valuable starting point for deeper investigations when combined with off-chain information. This focus on foundational insights is also why we do not estimate victim losses, as such calculations require significantly more data beyond on-chain analysis.

This chapter zeroes in on two prevalent forms of market manipulation: wash trading and pump-and-dump schemes. Wash trading involves artificially inflating trading volume by repeatedly buying and selling the same asset, creating a misleading perception of demand. Pump-and-dump schemes lure unsuspecting investors by driving up the price of an asset, often through coordinated hype, only for insiders to sell off their holdings at a peak, leaving unwitting holders of the asset with significant losses.

Keep reading as we delve into our methodologies for uncovering these suspicious patterns, providing a clearer view of how market manipulation manifests in the crypto space.

Heuristics enable identification of patterns of potential wash trashing, which show concentration in specific pools and among fewer actors

While there are subtle differences in the legal definitions of wash trading across jurisdictions, wash trades are generally understood to involve the near-simultaneous buying and selling of an asset without any change in beneficial interest, ownership, or market position.

Currently, most of the academic research on wash trading in crypto has been focused on centralized exchanges (CEXs), where possible motivations for inflating trade volumes include attracting users or climbing leaderboards. Unlike trading on CEXs, doing so on decentralized exchanges (DEXs) incurs gas fees, making wash trading potentially more expensive; nonetheless, such activity still exists.

Financial regulators around the world face challenges in identifying wash trading in traditional markets because collusion strategies vary and collusive transactions can be masked among normal trading activities. These challenges often take different forms in the crypto space, where pseudonymity, the use of decentralized platforms, and a lack of comprehensive regulatory oversight add complexity.

During our research, which primarily focuses on fungible tokens such as ERC-20 tokens and BEP-20 tokens, we encountered the following difficulties in identifying wash trading:

- Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) bots and arbitragers share characteristics with wash trading, as they buy and sell the same token pairs in very short time intervals. However, this activity is not typically directed at driving up volumes, but rather at capturing arbitrage opportunities.

- Most of the DEXs we studied are AMM-based (automatic market makers), rather than order book-based, as is common in most traditional financial markets. In order book-based markets, traders execute trades with a direct counterparty at a price set by one of the two parties to the transactions. In AMM-based markets, traders execute trades against a pool of assets supplied by liquidity providers at an algorithmically determined price. In the absence of a single trader sitting on both sides of a trade, it is more challenging to identify activity that would achieve a prearranged wash result. Additionally, because a trader lacks control over the quoted price for a transaction, it can also be challenging to determine whether the price is a result of an intentionally structured wash trade, rather than the price set algorithmically by the AMM.

Regardless, it is possible to look at on-chain activity to identify crypto addresses that exhibit patterns of potential wash trading activity, which we’ll demonstrate with an analysis of two relevant heuristics.

Wash trading Heuristic 1: matched buy and sell across transactions

For our first heuristic, we applied the following criteria to identify potential wash trades in a manner that avoids capturing MEV bot and arbitrager activity and excludes certain high-volume liquidity pools that are unlikely to be driven by wash trading. We looked for activity in which all three criteria were met:

- An address that executed one buy transaction and one sell transaction within 25 blocks (usually, 25 blocks are created within five minutes).

- The difference in the two transaction volumes in USD is less than 1%, which suggests that the trade did not yield a meaningful profit.

- A single address executed three or more trades that matched criteria 1 and 2 during the time period studied.

The first heuristic suggests that the combined wash trading volume on Ethereum, BNB Smart Chain (BNB), and Base was around $704 million in 2024. To put this into perspective, suspected wash trading volume identified by this heuristic accounted for 0.035% of the total DEX trade volume in November 2024.

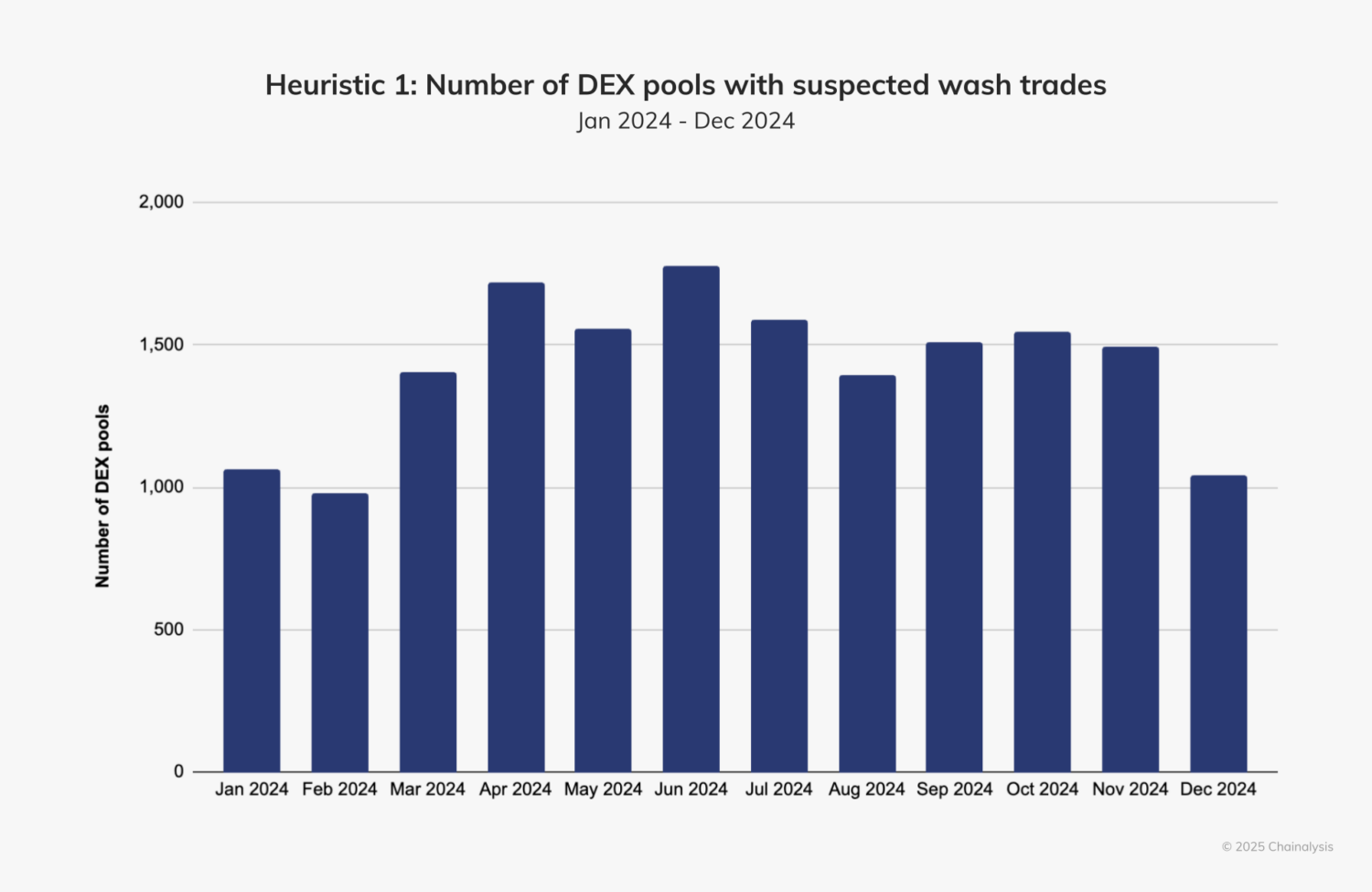

The volume increases in March, April, and June in the below chart were most likely due to a few DEX pools with very active suspected wash trading.

For instance, in April, five DEX pools accounted for a total of $78 million worth of suspected wash trading. Although suspected wash trading volumes fluctuated throughout the year, the number of DEX pools with associated activity remained fairly consistent, averaging around 1,000 to 1,800 pools per month, or between 0.2 and 0.3% of the approximately 500,000 pools active monthly, suggesting that wash trading may be concentrated in specific pools and/or driven by a small number of actors with targeted efforts.

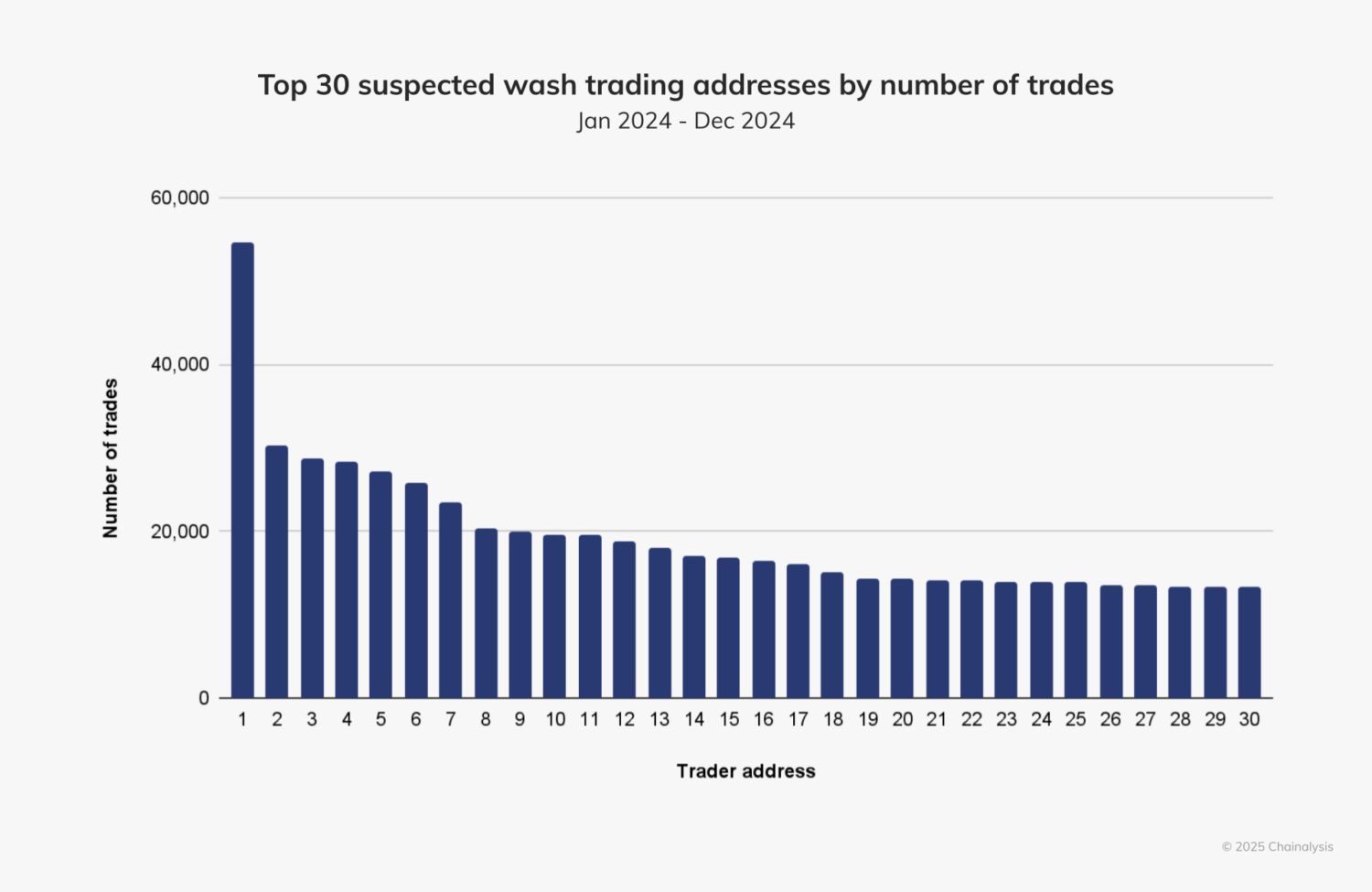

We were able to identify a total of 23,436 unique addresses across Ethereum, BNB, and Base exhibiting activity consistent with the Heuristic 1 criteria. On average, each address engaged with two DEX pools and initiated 129 suspected wash trades of $30,033 in total volume during the time period studied. However, as shown in the table below, addresses that traded with four or more DEX pools accounted for 10% of total addresses identified by Heuristic 1. These addresses accounted for 43% of the total suspected wash trading volume in 2024.

| Number of DEX Pools one address engages in | Total wash trade volume one address initiates (USD) | Number of wash trades one address initiates | |

| Average | 2 | $30,033 | 129 |

| Median | 1 | $651 | 10 |

| 75 percentile | 2 | $5,940 | 25 |

| 90 percentile | 4 | $32,249 | 102 |

| Max | 241 | $17,334,934 | 54,684 |

One address in 2024 initiated more than 54,000 buy-and-sell transactions of almost identical amounts — very suspicious in itself — illustrating the scale of this potential activity.

Wash trading Heuristic 2: disperse-based detection

For our second heuristic, we looked at activity across token multi-senders, which were originally developed to simplify payments by facilitating simultaneous transfers of different tokens to multiple addresses. Unfortunately, many bad actors exploit these services to distribute funds across numerous addresses, managing them algorithmically in an attempt to conceal that the same actor is potentially manipulating tokens.

With this in mind, we employed the following criteria to identify suspected wash trading, accounting for ETH and BNB transfers by two multi-sender applications, and removing major pools that are unlikely to involve wash trading:

- Controller addresses that send funds to five or more managed addresses.

- Managed addresses that received their first ETH or BNB deposit from the corresponding controller address through a token multi-sender.

- The difference in the total USD value between the buy and sell sides executed by managed addresses in a single liquidity pool is less than 5%.

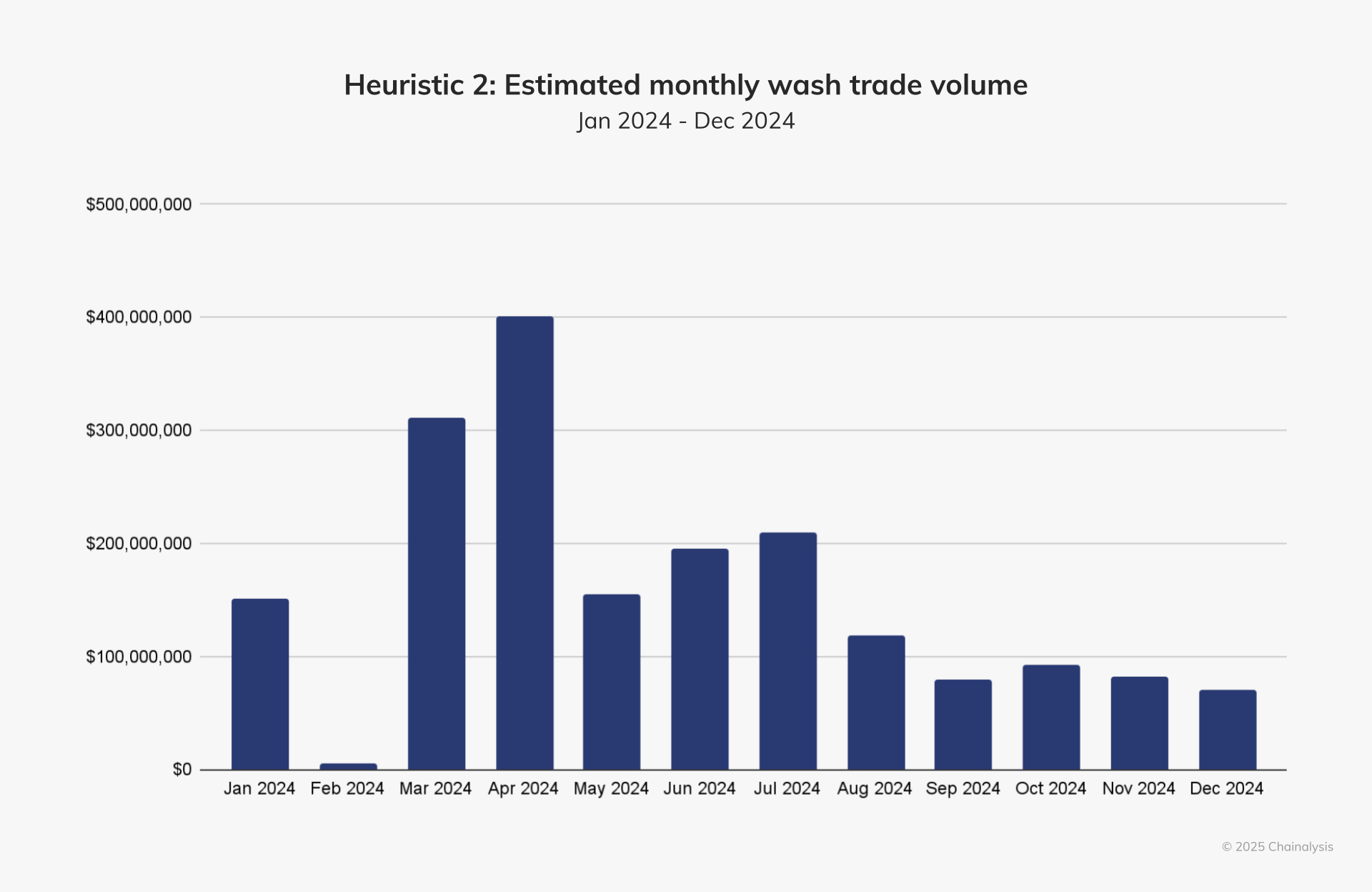

Heuristic 2 suggests that the combined wash trade volume on Ethereum, BNB, and Base was around $1.87 billion in 2024. In November 2024, the suggested wash trade volume accounted for 0.046% of total DEX volume.

Similar to the first heuristic, the spikes observed between March 2024 and April 2024 in the below chart coincide with the activity of 2024’s most prominent operators. For instance, in April, three controller addresses alone accounted for $318 million in suspected wash trading volume.

In January 2024, one controller address was responsible for approximately $142.99 million in suspected wash trade volume. Although the monthly estimated wash trade volume fluctuated significantly throughout 2024, the number of active controller addresses was more consistent, experiencing a steady upward trend between January and June.

Upon examining these addresses more closely, we learned that controller addresses managed an average of 183 addresses in 2024. As shown in the table below, a single controller address can manage tens of thousands of addresses.

| Number of addresses one operator controls | |

| Average | 183 |

| Median | 7 |

| 75 percentile | 21 |

| 90 percentile | 100.00 |

| Max | 22,832 |

In 2024, the average suspected wash trade volume for one controller address was around $3.66 million in 2024. As we see in the chart below, the maximum volume of suspected wash trading controlled by one address can reach the hundreds of millions of dollars, illustrating the potential scale of this inflated activity.

| Total wash trade volume one operator executes (USD) | |

| Average | $3,661,934 |

| Median | $11,742 |

| 75 percentile | $223,446 |

| 90 percentile | $1,918,388 |

| Max | $313,585,875 |

Heuristics 1 and 2 use different methodologies in order to detect different potential wash trading tactics. By adding the totals from heuristic 1 ($704 million) and heuristic 2 ($1.87 billion), we identify a total of $2.57 billion in potential wash trading activity. It is possible that there is overlap in the amounts detected by each heuristic – in other words, some suspected wash trading activity may have been detected by both heuristics – and so we consider this an upper bound estimate for this methodology.

Wash trading case study: volume boosting bot, Volume.li

Wash trading has emerged as a key concern in cryptocurrency market integrity, drawing the attention of U.S. regulators and law enforcement. For instance, on October 9, 2024, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charged four market makers — ZM Quant, Gorbit, CLS Global, and MyTrade — for generating artificial token trading volume. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) later reported that this wash trading scheme involved 18 individuals and entities operating an international trading scheme with touchpoints in the U.K. and Portugal.

In this case, the market makers conducted the alleged illicit trading by operating trading bots that created artificial token volume. Typically, the strategy of building and operating bots for this purpose is difficult to distinguish from ordinary trading on both CEXs and DEXs.

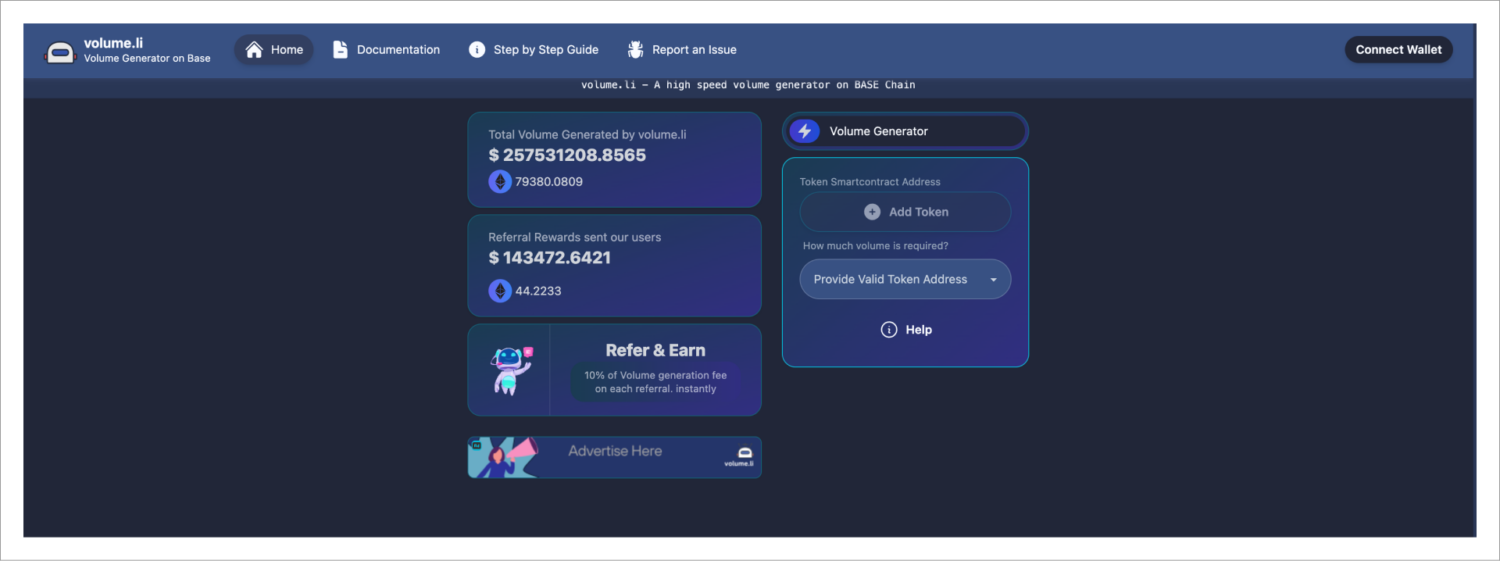

To explore in-depth how this process typically works, we looked at a boosting bot service called Volume.li, which provides trading bots to customers who want to create fake volume on DEXs. While this service was not used by those charged by the SEC in the case above, it demonstrates how wash traders may leverage a tool to conduct similar activity. According to its website, Volume.li has generated a total of $257.5 million in trading volume to date.

Customers have the option of purchasing bots of varying degrees of volume, from $50 to $100,000, within 24 hours. The Volume.li site states that a bot generating $100,000 in volume within 24 hours costs 0.212 ETH. After the customer pays this fee, the bot will buy and sell a token 100 times in rapid succession.

In the below example, a purchased trading bot generated fake trades of the SoylanaManletCaptainZ token (ANSEM) paired with wETH on Uniswap.

We discovered that this trading bot uses a specific function (0x5f437312) to initiate its trades. Typically, swaps in Uniswap are initiated when the router contract receives a transaction, meaning that the contract is the recipient. However, in these types of trades, a few addresses — likely controlled by Volume.li — send transactions to the smart contracts they manage, invoking the 0x5f437312 function. These smart contracts act as intermediaries, subsequently triggering multiple wash trade transactions on Uniswap.

One example of an asset with trading volume boosted by Volume.li is the Donald J. Chump token, which had 6,939 holders as of January 2025. Within five days, Volume.li’s bot generated 10,341 pairs of buy and sell orders using five different addresses, creating a total of $39,723 in fake trading volume. From July 27 to July 30 the token issuer relied heavily on Volume.li to generate liquidity, which accounted for approximately 43% of the token’s total trading volume on Uniswap.

As Volume.li exemplifies, even when our starting point is off-chain, pairing open-source research on platforms of interest with our own heuristics can yield powerful insights about potential on-chain market manipulation.

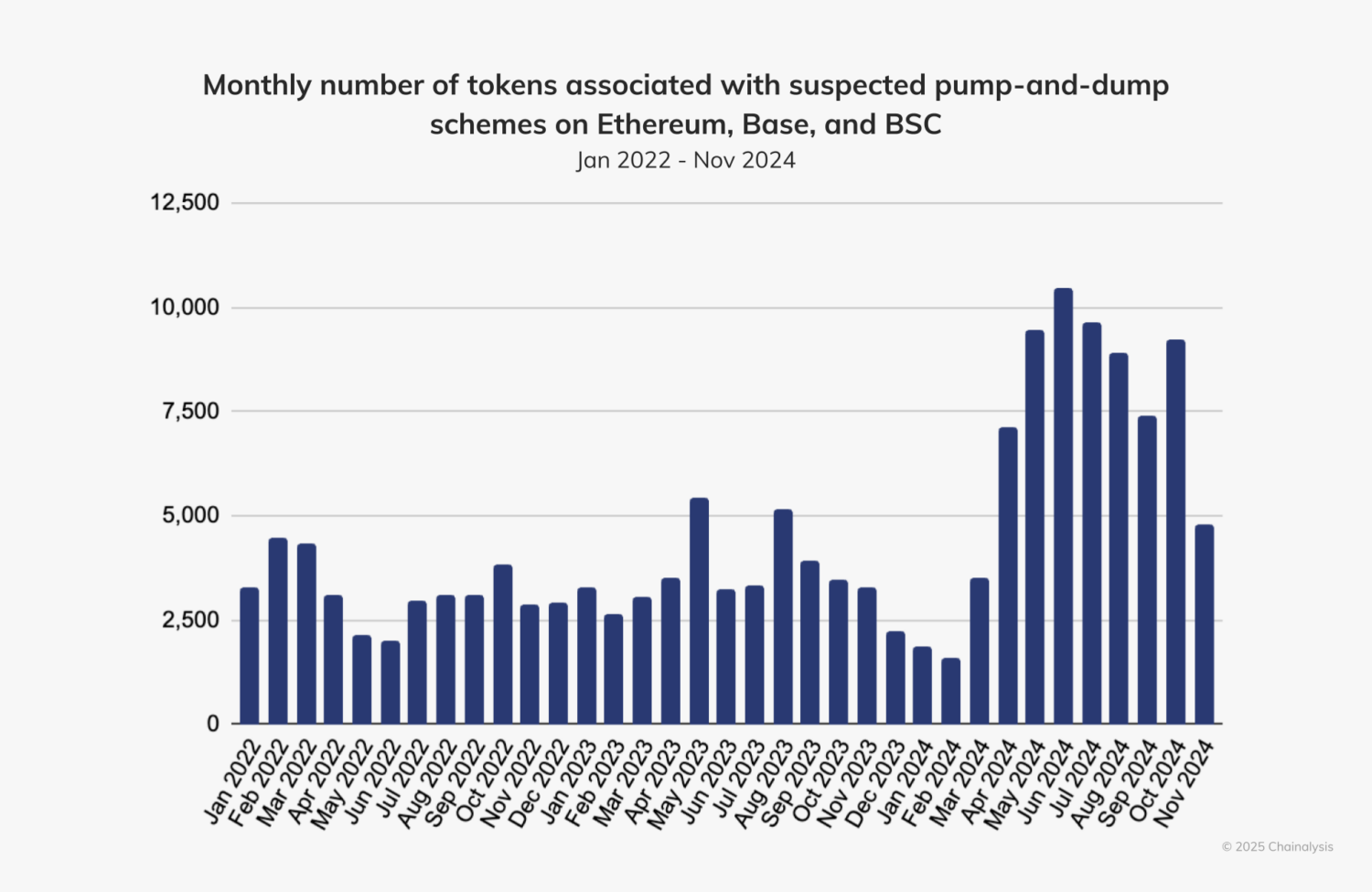

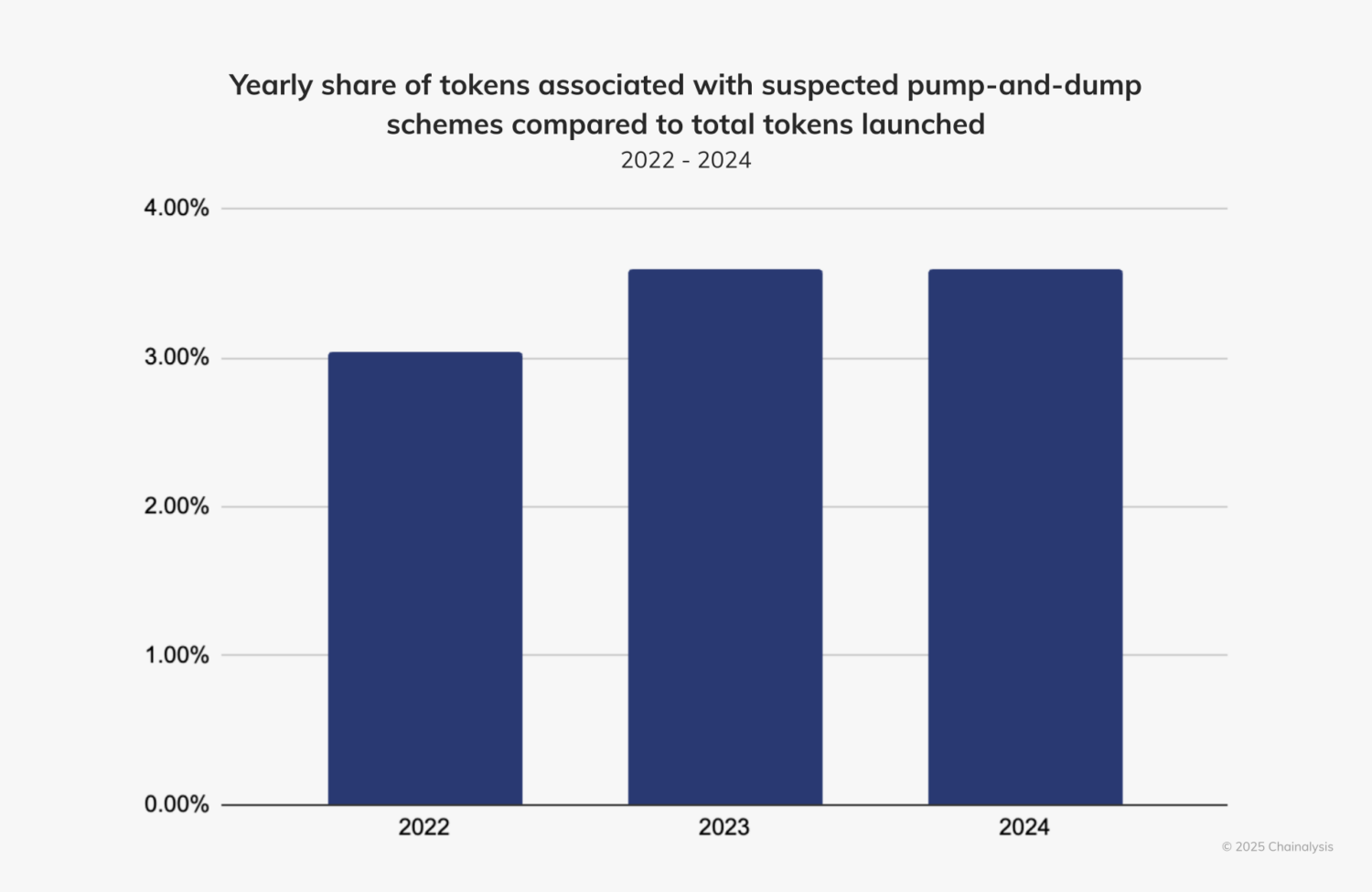

3.59% of all launched tokens in 2024 display patterns that may be linked to pump-and-dump schemes

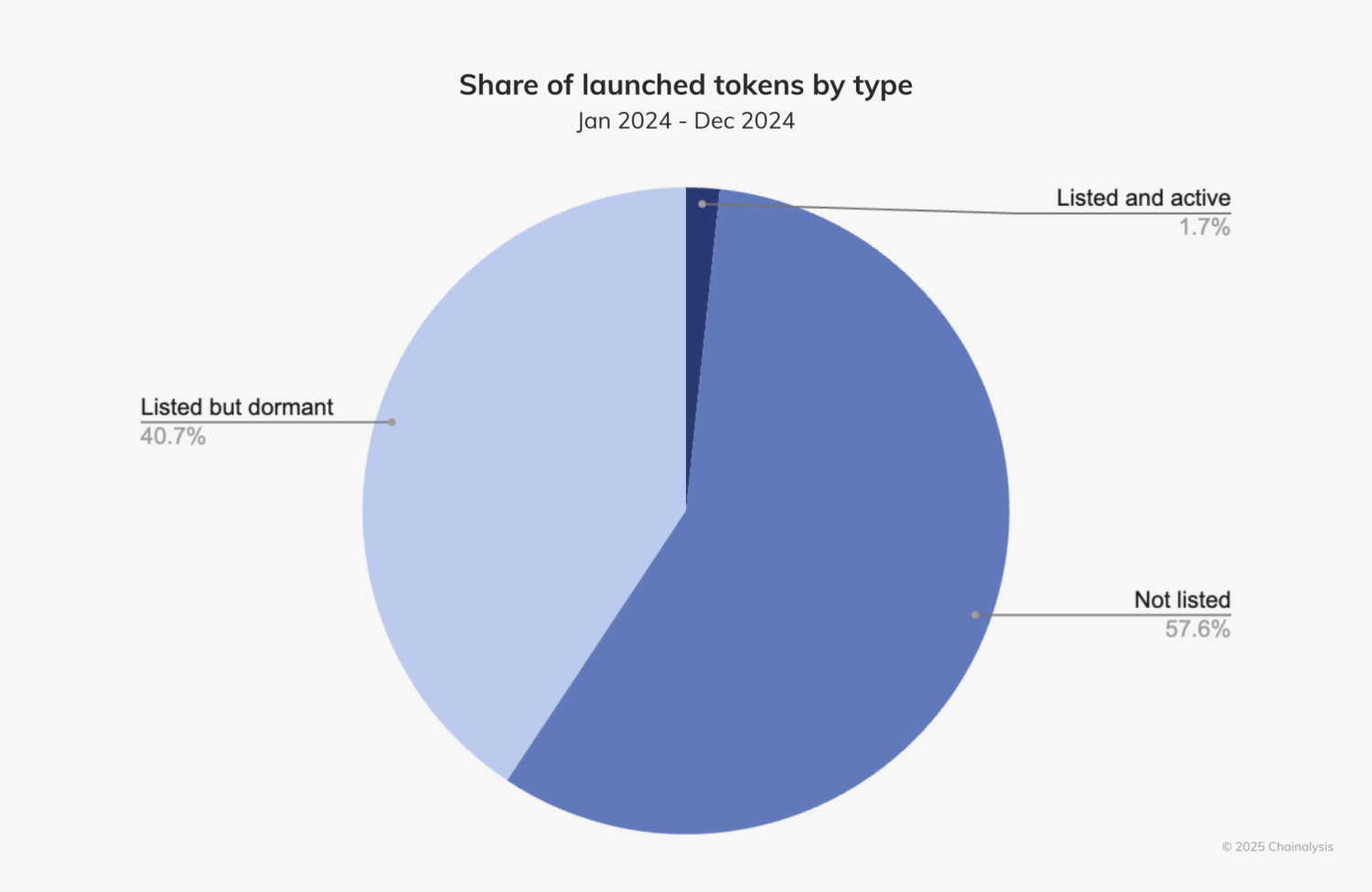

In 2024, more than 2 million tokens were launched in the blockchain ecosystem, approximately 0.87 million of which (42.35%) were listed on a DEX.

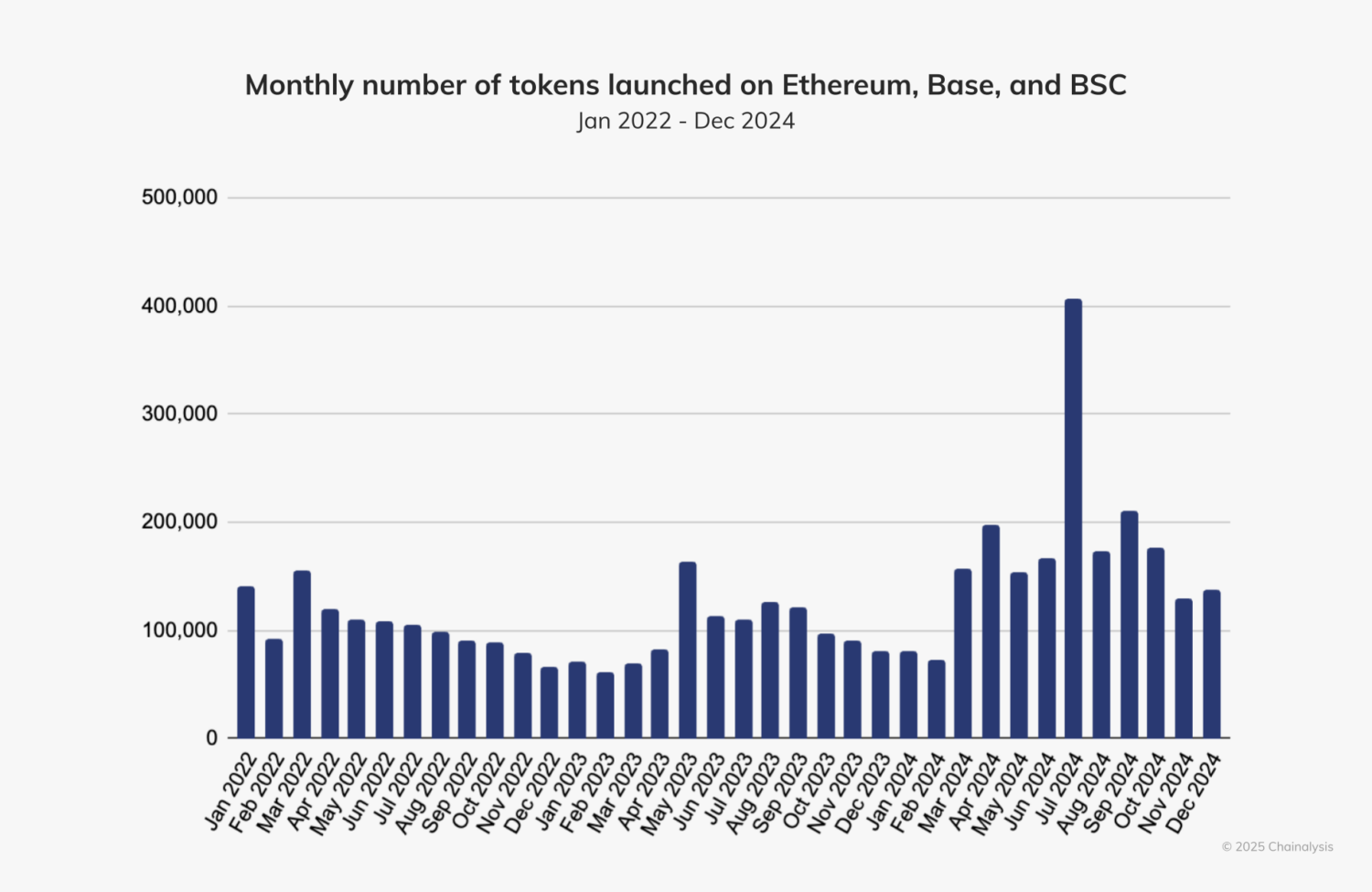

Last year, we noted that the majority of new tokens were developed on Ethereum due to the ease of creating tokens using the ERC-20 standard. Although Ethereum is still the chain with the greatest number of tokens actively traded on DEXs, we’ve noticed many token creators using other chains, such as BNB and Base. In the below chart, we see that, in most months in 2024, several hundreds of thousands of tokens were launched on these chains, with July seeing more than 400,000.

Despite the staggering number of tokens launched in 2024, only a small fraction (1.7%) have been actively traded within the last 30 days. So, why do so many of these tokens appear dormant? One possibility is that many are abandoned shortly after their creation, potentially due to a lack of interest or failure to gain traction. It is also possible that some of these tokens facilitate intentional short-lived schemes designed to exploit initial hype before fading away, also known as pump-and-dumps or rug pulls.

Here’s an example of how a pump-and-dump scheme might work with a token:

- A crypto participant either launches a new token or buys a large share of the supply for an existing token — usually one with historically low volume.

- This participant hypes up the token using social media and/or online chat rooms.

- The hype attracts attention from other users, leading to an increase in buying pressure on the token.

- The initial participant may also engage in wash trading, as described in the previous section, in order to further artificially inflate the token’s trading volume.

- If these methods are successful, the token rises in value.

- Once the token reaches the desired price target, the original participant liquidates their position for a profit.

- The token’s price rapidly drops due to selling pressure, leaving many victims “holding the bag.”

- If the participant is also the token creator or one of the liquidity pool’s primary liquidity providers, they may also completely abandon the project in a rug pull, taking more users’ funds with them. In certain cases, however, governance protocols may not allow this.

It is possible to identify many of these activities using on-chain analysis, and we used the following criteria to identify potential pump-and-dump schemes. We looked for activity in which all three criteria were met:

- An address that added value to a token’s liquidity pool and subsequently removed at least 65% of the pool’s liquidity, valued at $1,000 or more.

- The token’s liquidity pool is no longer active.

- The liquidity pool had previously gained traction, with more than 100 transactions occurring in it.

We made several changes to our methodology this year, employing stricter criteria to improve accuracy. First, we loosened the liquidity removal threshold from last year’s 70% to 65% to capture tokens with larger liquidity volumes. We also replaced the criterion of a token having liquidity worth $300 or less with a completely inactive liquidity pool (we consider a liquidity pool inactive if no transactions occurred in the last 30 days). And finally, we replaced the original criterion of a token being purchased at least five times by DEX participants with no on-chain connection to the token’s biggest holders, with the criterion of the liquidity pool having more than 100 transactions.

| Number of tokens | Percent of all tokens launched | |

| Number of tokens launched in 2024 | 2,063,519 | 100% |

| Number of tokens listed on DEX | 873,957 | 42.54% |

| Number of suspected pump-and-dump tokens | 74,037 | 3.59% |

Approximately 94% of DEX pools involved in suspected pump-and-dump schemes appear to be rugged by the address that created the DEX pool. The other 6% appear to be rugged by the addresses that were funded by the pool or token deployer. In some cases, the pool deployer address and the address that rugged the pool were funded by the same address source, suggesting there may have been a coordinated effort to exploit users.

| Total | |

| Number of pools dumped by the same actor who deployed the DEX pool | 69,897 |

| Total number of DEX pools engaged in suspected pump-and-dump schemes | 74,312 |

| Share of pools dumped by the same actor who deployed the DEX pool | 94.00% |

After a DEX pool is launched, it typically takes a few days to a few months before the associated token is abandoned. As we see in the table below, it took an average of six to seven days, and 1% of suspected pump-and-dump schemes lasted longer than four to five months.

| Total | |

| Average in days | 6.23 |

| Median in days | 0 |

| 75 percentile in days | 0 |

| 90 percentile in days | 8 |

| 99 percentile in days | 123 |

Navigating the challenges of crypto market manipulation

Market manipulation remains a critical concern for both crypto industry participants and authorities as they strive to keep pace with the rapidly-evolving sector. The complex and dynamic nature of market manipulation, compounded by crypto’s unique characteristics — such as its pseudonymity and decentralization — heightens the challenge. A robust and coordinated approach is therefore essential — one that fully harnesses the power of on-chain data and analytics to enable proactive detection and prevention of manipulative activities.

This website contains links to third-party sites that are not under the control of Chainalysis, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Chainalysis”). Access to such information does not imply association with, endorsement of, approval of, or recommendation by Chainalysis of the site or its operators, and Chainalysis is not responsible for the products, services, or other content hosted therein.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.