In recent years, cryptocurrency scams have become increasingly personalized, directly targeting individual wallet holders with alarming frequency and devastating consequences. These scams often focus on high-value targets or those with frequent, regular crypto transactions. While widespread pig butchering and approval-phishing campaigns have already cost victims billions of dollars, another type of crypto scam is also on the rise: address poisoning attacks.

What is an address poisoning attack?

An address poisoning attack is a particularly pernicious crypto scam that uses customized on-chain infrastructure to deceive victims out of their funds. The approach is simple, yet highly effective:

- Scammers begin by studying a target’s transaction patterns, looking for frequently used addresses.

- The scammers will then algorithmically generate new crypto addresses until they create one that closely resembles the address that the target most often interacts with.

- Once they have a convincing lookalike address, the scammer then sends a small, seemingly harmless transaction from this newly generated address, effectively “poisoning” the target’s address book.

The hope is that, when the target sends funds in the future, they will rely on their transaction history for convenience and mistakenly send funds to the scammer’s look-alike address instead of to the intended recipient address.

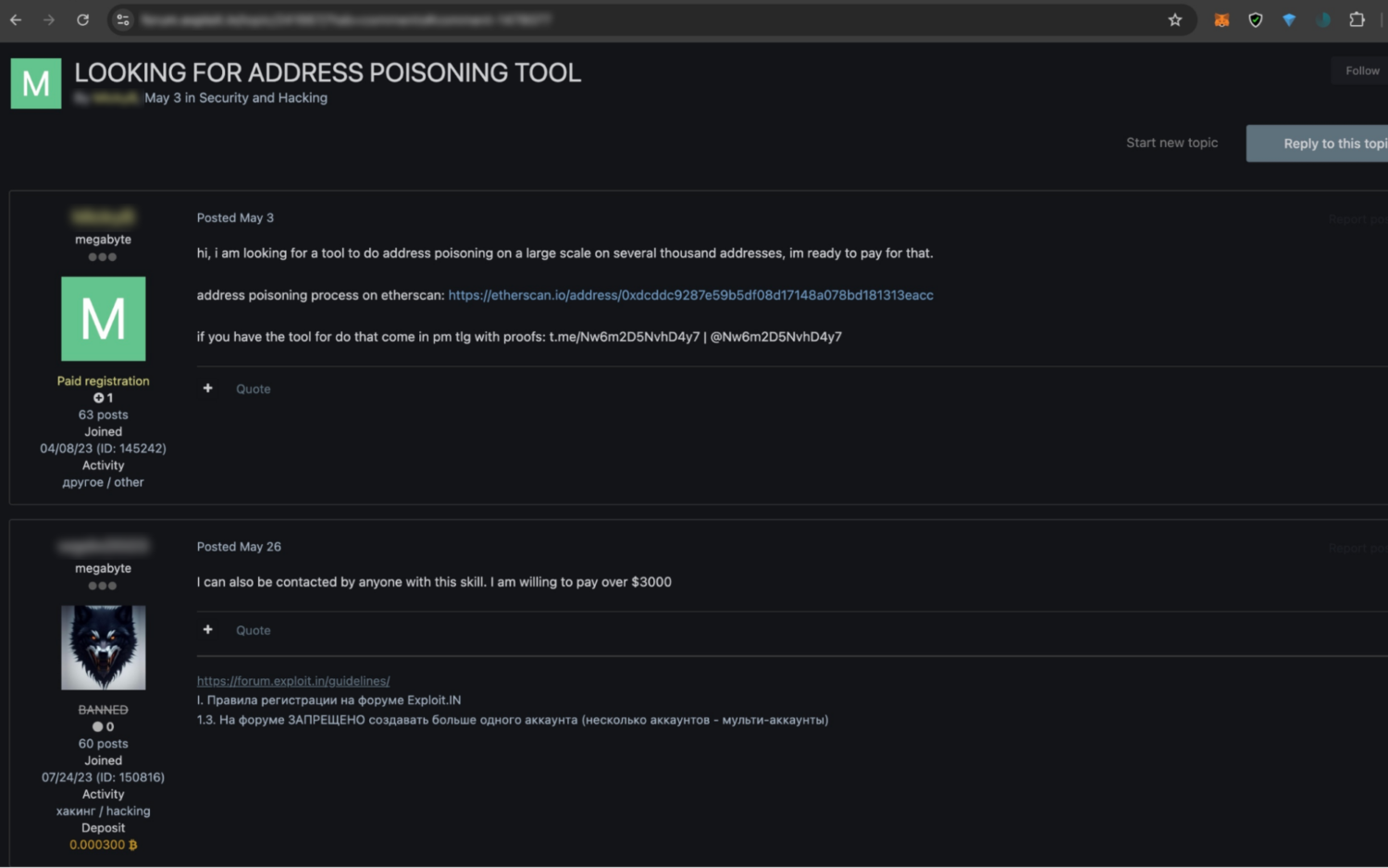

Similar to other forms of cybercrime like ransomware, address poisoning campaigns are often designed to be plug-and-play. On the dark web, scammers can easily purchase address poisoning toolkits, widely advertised in darknet marketplaces. These kits usually feature user-friendly interfaces, making it simple for even those with limited technical expertise to conduct sophisticated scams. The toolkits often include software for generating look-alike addresses that mimic those frequently used in a target’s wallet, automated scripts to seed or dust those addresses with small payments, and detailed instructions on how to mislead victims by exploiting their blockchain transaction history.

Below we see an individual seeking purchase of such a toolkit.

Many vendors offer additional services, such as comprehensive tutorials, step-by-step guides, and even customer support via encrypted messaging platforms. Transactions for these kits are typically conducted in cryptocurrency.

The widespread availability of these toolkits has lowered the barrier to entry for scammers, contributing to the growing prevalence of address poisoning attacks in the crypto space.

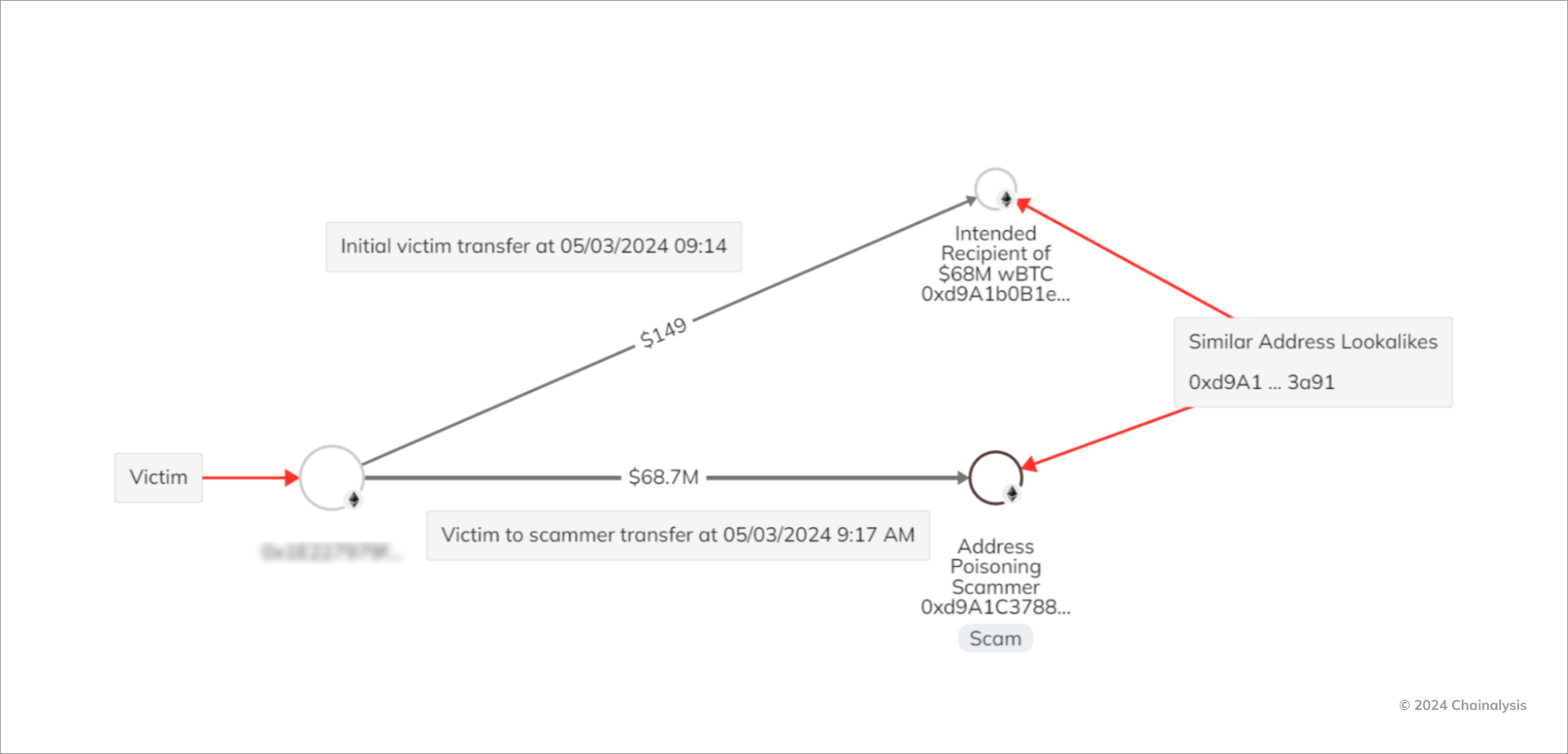

As detailed in our Mid-year Crime Update, one of 2024’s biggest scams was an address poisoning attack that took place on May 3rd. This incident nearly cost an unknown crypto whale $68 million in wrapped bitcoin (WBTC) before the attacker returned the funds to the victim. We’ll dissect how this event unfolded on-chain and explore how this type of scam can be mitigated.

Address poisoner spears a crypto whale

The event begins with an initial transfer on 3 May 2024 at 9:14 UTC from the victim (0x1E227) to 0xd9A1b, a seemingly benign address on the Ethereum blockchain. This was likely a test payment, which is a routine best practice when moving large amounts of value on-chain.

Just minutes later, the victim made a second transfer, this time unknowingly to an address controlled by the scammer, 0xd9A1c, which at a casual glance, looks to be the same “0xd9A1,” if you only reference the first six characters. In this transaction, the victim transferred approximately $68 million in wrapped bitcoin (WBTC) to the scammer. By 14:44 UTC, the scammer had moved $71 million in WBTC (a larger amount due to appreciation in the price of BTC) to another address on-chain.

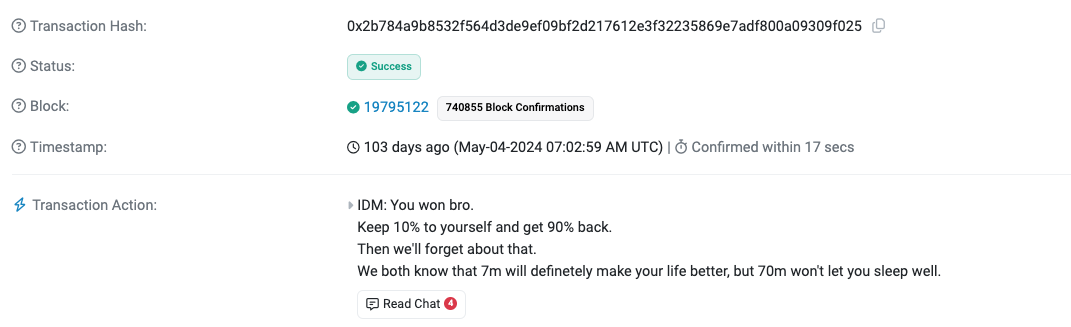

In the days that followed, the victim sent a flurry of messages embedded in small ether (ETH) transactions, attempting to negotiate with the scammer for the return of at least $61 million of the stolen funds.

One message in particular included a thinly veiled threat from the victim: “We both know there’s no way to clean this [sic] funds. You will be traced. We also both understand the “sleep well” phrase wasn’t about your moral and ethical qualities.”

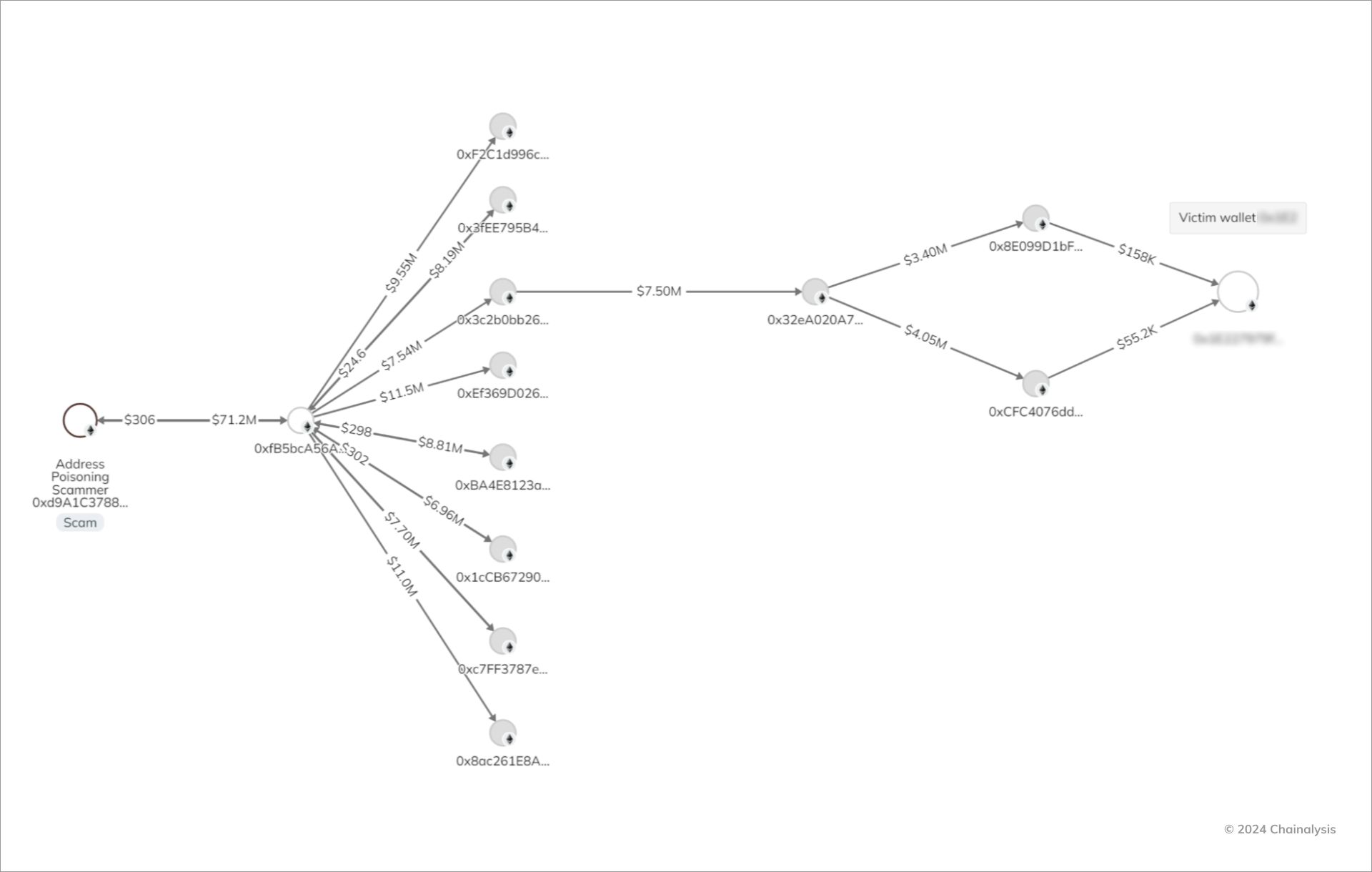

The scare tactic appeared to be effective, as the scammer returned the original $68 million in ETH on May 9th to the victim’s wallet — but not before pocketing $3 million due to token appreciation, sending funds back through several intermediary wallets first.

The Chainalysis Investigations graph below shows one such path from the initial address poisoning address back to the victim wallet through several intermediary wallets.

Mapping the broader campaign

Tracing activity from a single address, we uncovered a network of 8 “seeder” wallets responsible for launching address poisoning attacks for this campaign.

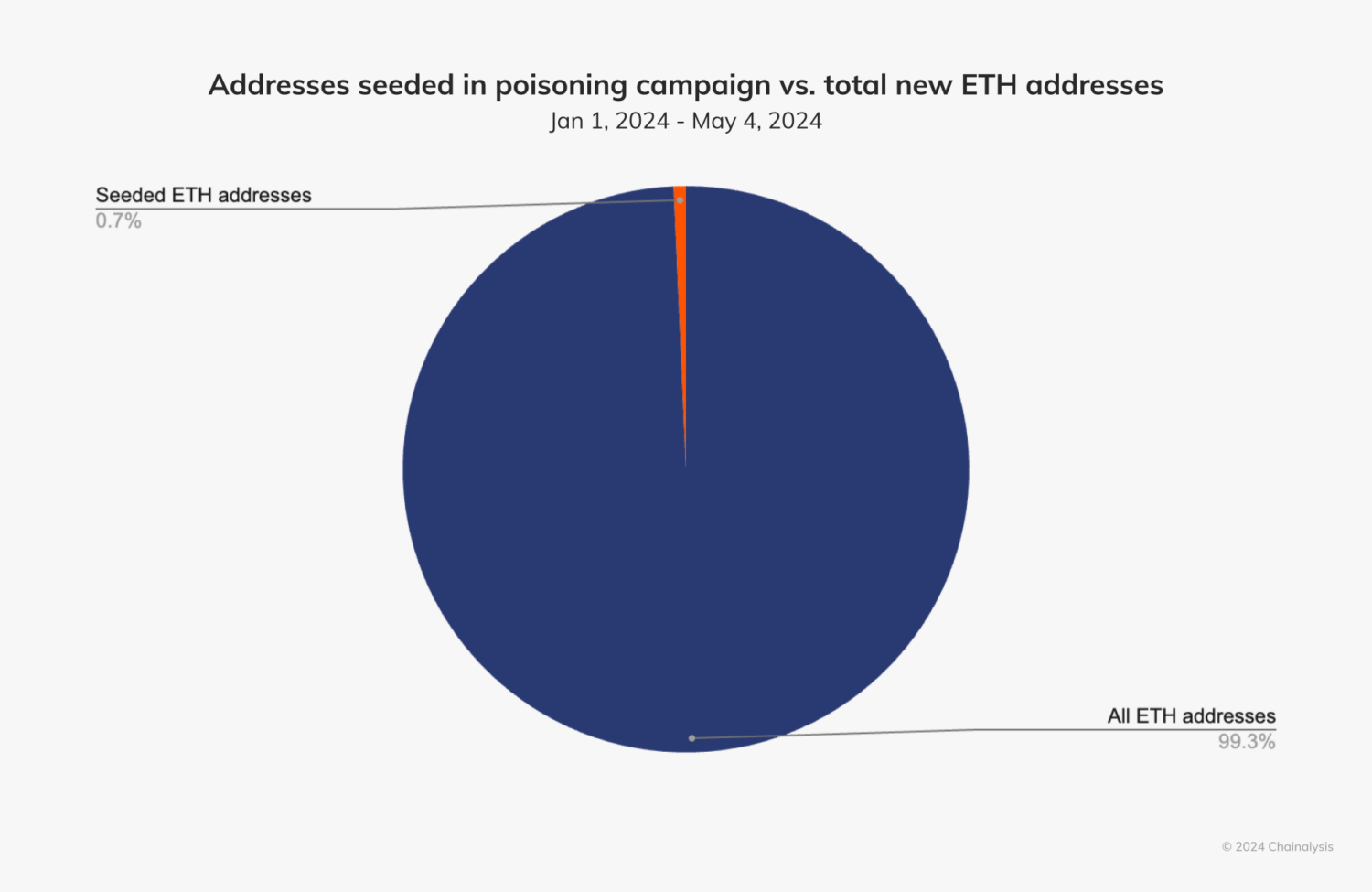

Each seeder wallet created additional seeder wallets and numerous “seeded wallets” — addresses similar to those of intended target addresses. In total, we identified 82,031 potential seeded addresses linked to this scam, all generated to deceive potential victims. This mapping effort likely underrepresents the campaign’s full extent, underscoring the broad impact address poisoning can have.

The scale of this campaign cannot be understated. In particular, the pool of seeded addresses launched by the scammer accounts for slightly under 1% of all new Ethereum addresses created during the period of the scam campaign.

Profiling victims of the campaign

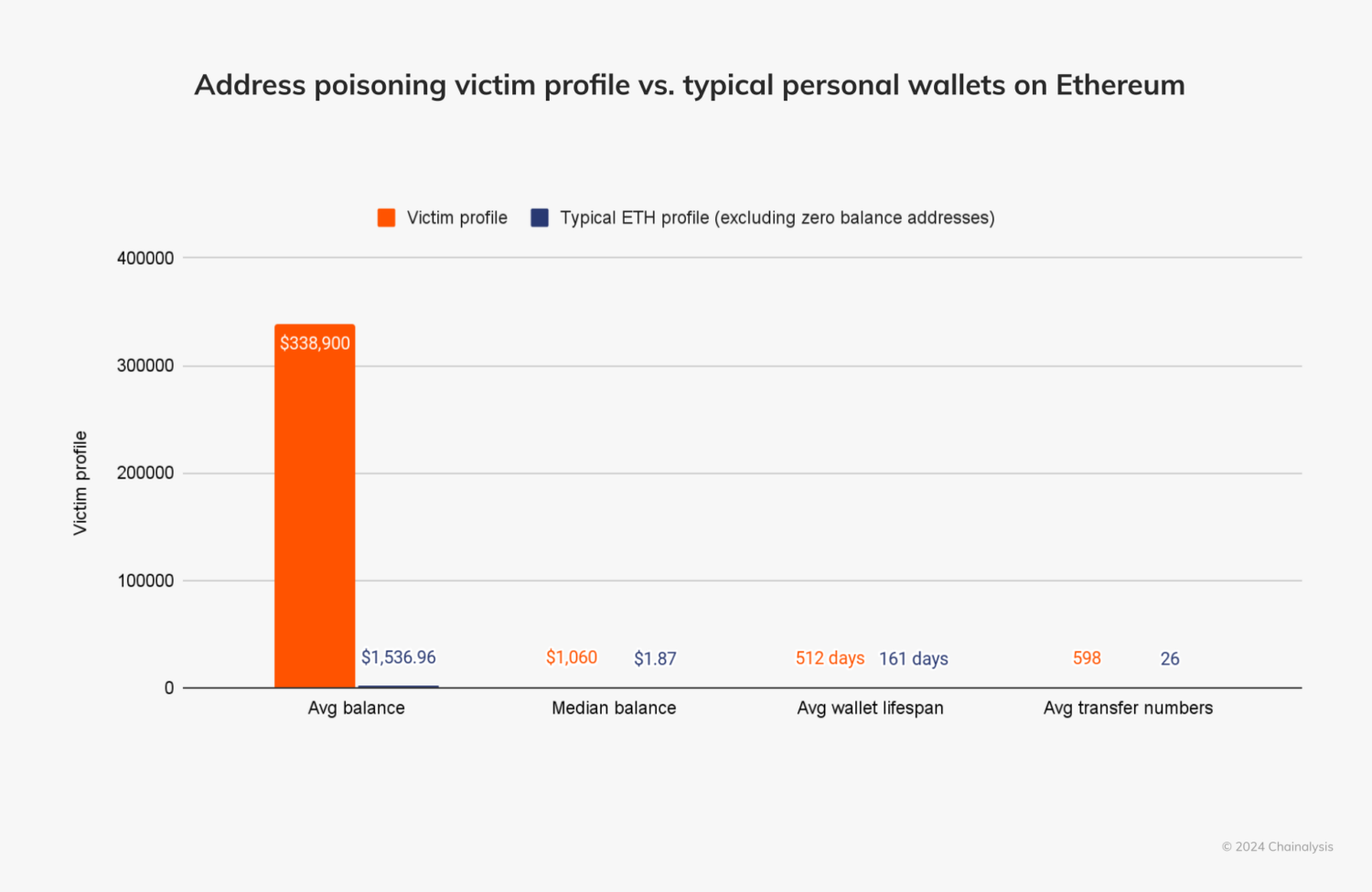

Data reveals that the address poisoning scam targeted more experienced users with higher wallet balances compared to the typical wallet holder. A total of 2,774 addresses sent funds (totaling $69,720,993) to the aforementioned 82,031 addresses, representing the victim pool for this campaign.

The chart below shows the typical characteristics of these victims and compares them to typical Ethereum personal wallets that were active on-chain for a similar period of time, from March of 2018 through October of 2024.

On average, victim wallet balances exceeded $338,900, with a median balance closer to $1,000. These wallets had also participated in an average of 598 transfers and had been active on-chain for about 512 days.

This demonstrates that victims of this addressing poisoning campaign are generally more active crypto users with larger wallet balances, more transactions, and a longer on-chain history than the average ethereum wallet holder. While new users, who may find crypto confusing, are often prime scam targets — anyone can be a target. What stands out is that some scams, such as this campaign, instead specifically target higher-value and more active participants. As the sophistication of scams grows, so does the importance of broader awareness of security practices and crypto wallet hygiene.

Measuring the success of the campaign

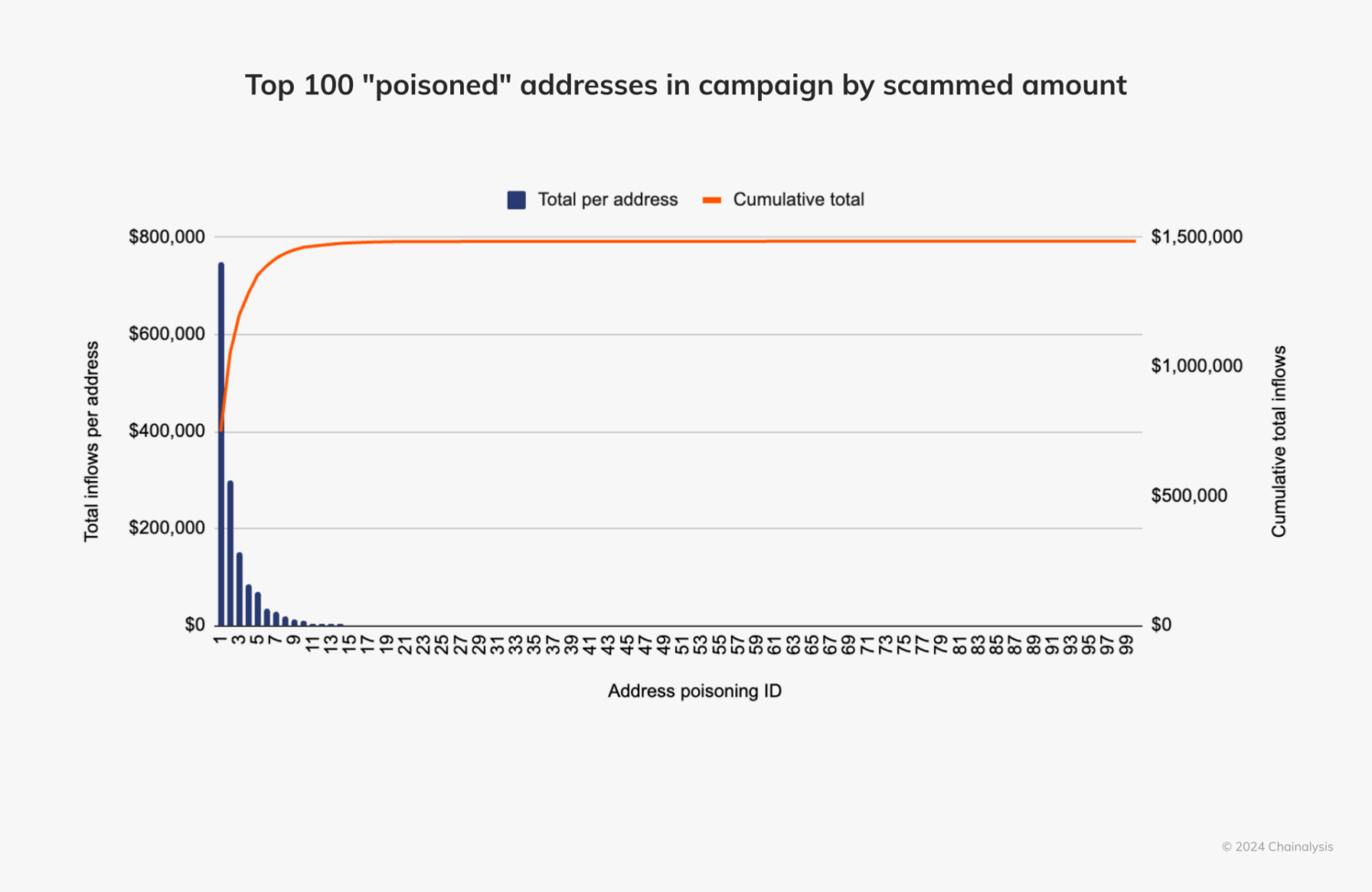

Overall, the success rate of the address poisoning campaign was very low — only 0.03% of the fake addresses received more than $100 from victims (not including transfers from the scammer.) This means that most of the 82,031 addresses seeded for the scam did not successfully trick people into sending large amounts.

It’s interesting to note that 756 addresses did send smaller amounts, between $1 and $100, which were likely test payments. Fortunately, since those test payments did not reach the intended address, it prevented further losses, showing how useful the practice of small test transactions can be for irreversible on-chain transactions.

Even though the success rate per address for the campaign was very low, the potential return on investment (ROI) was extraordinary. Had the scammer kept the original $68 million, the overall ROI would have been an astonishing 58,363% (584 times the initial amount). Even after returning the $68 million to the victim, the scam still netted $1.49 million, resulting in an impressive ROI of 1,147.62% (or 12.47 times the cost.)

This return was achieved over a 66-day period, from February 28 to May 4, 2024, with the $68 million scam occurring near the very end of the campaign window on May 3rd – with the funds ultimately returned to the victim on May 9th.

The success of the address poisoning campaign was heavily skewed toward a small number of addresses. Excluding the returned payment, only 22 of the campaign’s more than 82,000 addresses received over $100 from sources other than the scammer. While most addresses failed, a few high-value targets drove the majority of profits.

Compared to all scams that began in 2024, this campaign’s amount yielded stands out. The typical scam campaign from 2024 made a median amount of about $400 according to our data. This makes the address poisoning campaign, which yielded $3 million excluding the returned $68 million payment, 3,727 times larger than the median scam profit from this year.

Cashing out non-returned proceeds

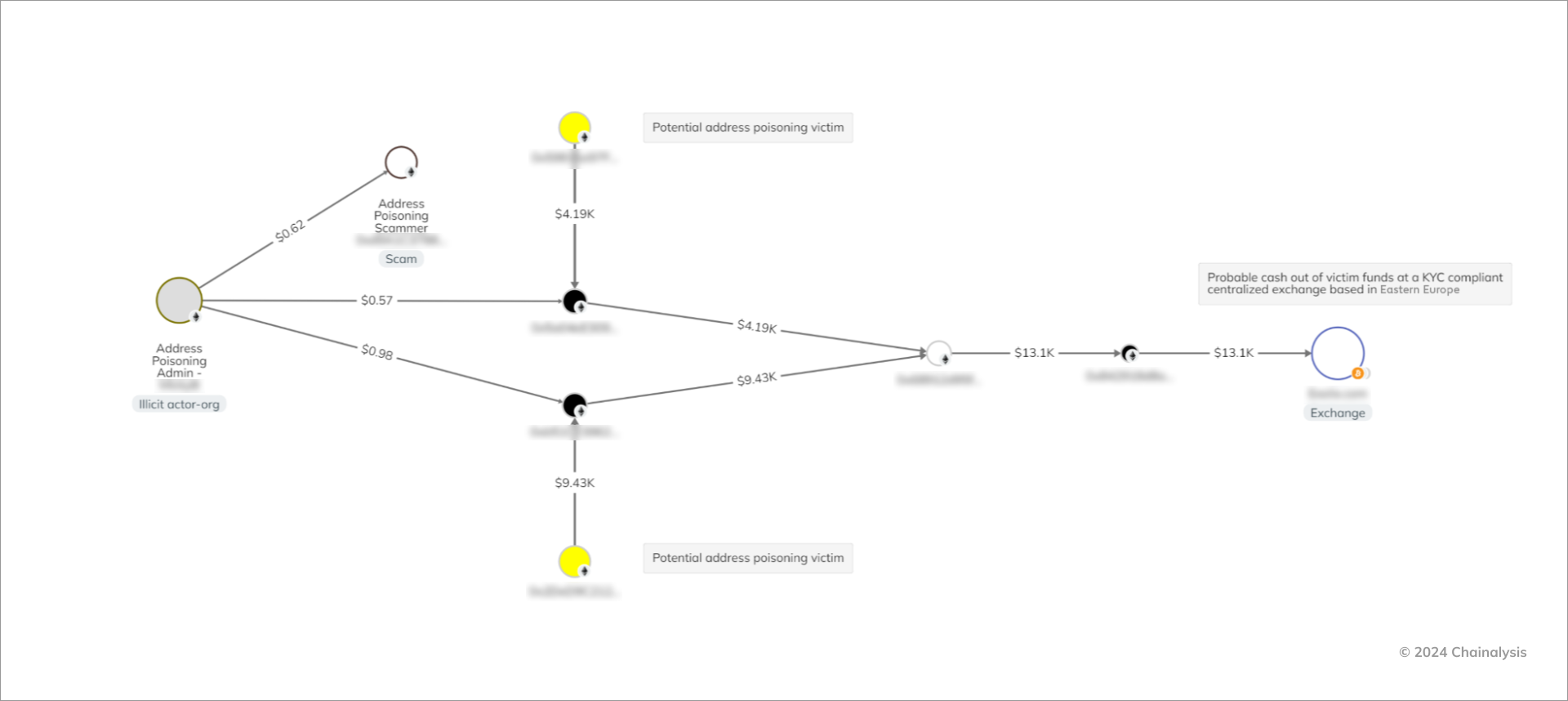

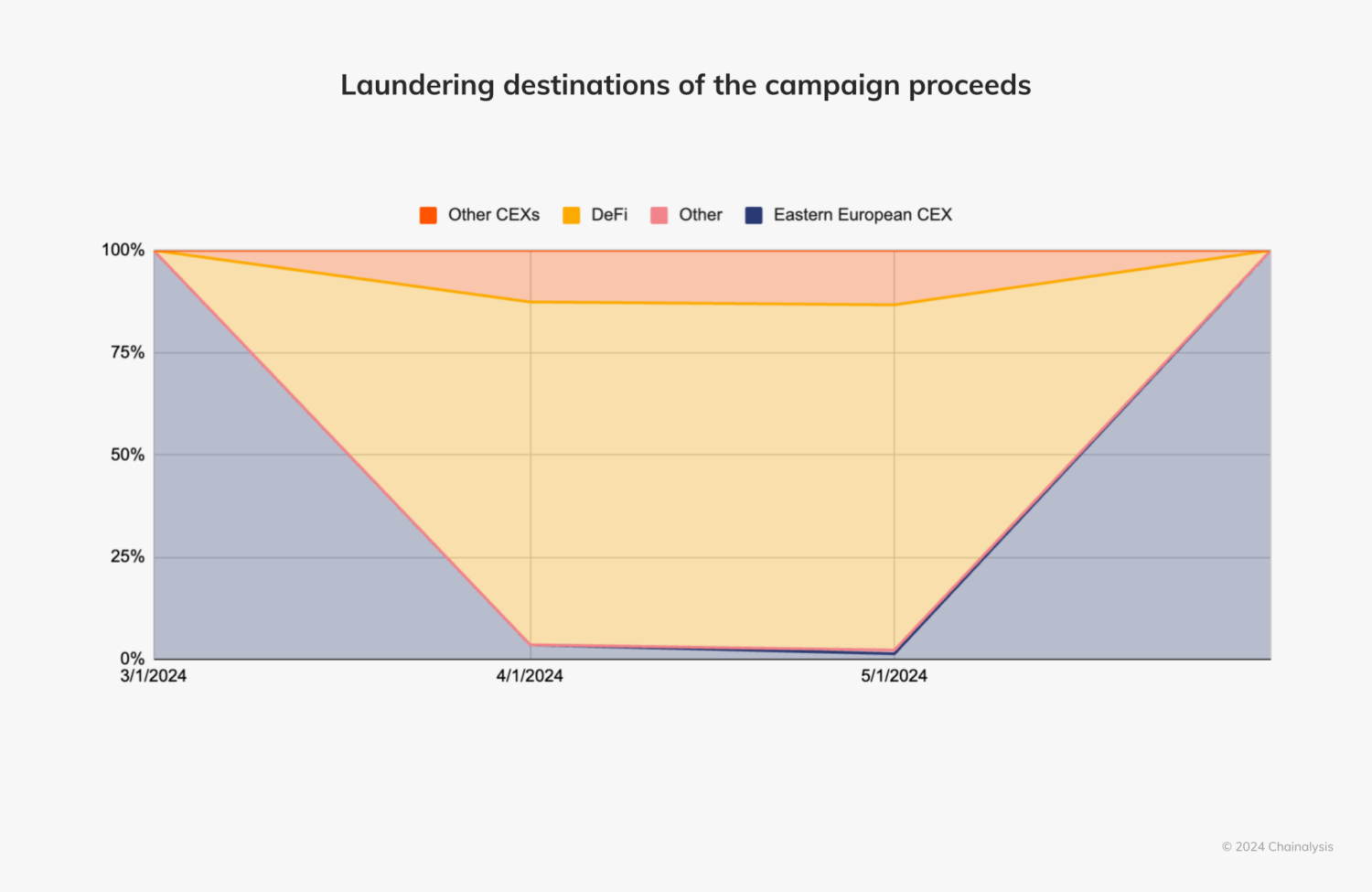

The threat actor behind this address poisoning campaign returned $68 million to the victim, which was unusual and signaled the end of this series of attacks. Throughout most of the campaign, the scammer had been stealing proceeds from victims and laundering through DeFi platforms or centralized exchanges.

The Chainalysis Investigations graph below details a series of victim payments to wallets controlled by the threat actor. The scammer then consolidated these funds and transferred them to a KYC-compliant centralized exchange (CEX) based in Eastern Europe.

Looking at the bigger picture, we can see how the scammer handled stolen funds throughout the campaign. The CEX played a key role in the laundering process, with a large portion of stolen funds sent there at both the beginning and end of the campaign.

Although the scammer also used other CEXs, the middle portion of the campaign involved significant activity on DeFi protocols. This suggests they may have been trying to launder the funds during the course of the scam.

Blockchain intelligence is key to fighting address poisoning scams

Though smaller in scale compared to other major crypto fraud, address poisoning attacks stand out for their short duration and exceptionally high ROI. These scams exploit the fast-paced, complex nature of blockchain transactions, targeting victims who may forget to carefully check addresses. As address poisoning becomes more prevalent, it signals a troubling trend that scams are evolving, becoming harder to detect, and even with fewer victims, can still quickly steal substantial sums.

The decentralized and transparent nature of the blockchain provides a wealth of data, but the challenge lies in turning this raw information into actionable insights. In the context of scams like address poisoning where attribution may not always be clear, certain “red flag” behaviors, such as repeated large denomination transfers that deviate from a user’s typical behavior, can be monitored in real-time. Moreover, real-time heuristics can help identify addresses that are potentially involved in an address poisoning campaign. These insights can form the basis of alerts, notifying the ecosystem that such funds may be linked to fraudulent activity.

Chainalysis empowers the ecosystem with the technology to detect these activities, playing a critical role in mitigating scams like address poisoning by identifying suspicious patterns, tracing illicit fund movements, and detecting anomalies in real-time. By enabling security teams and authorities to intervene sooner, we can prevent further damage and protect ecosystem participants.

This website contains links to third-party sites that are not under the control of Chainalysis, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Chainalysis”). Access to such information does not imply association with, endorsement of, approval of, or recommendation by Chainalysis of the site or its operators, and Chainalysis is not responsible for the products, services, or other content hosted therein.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.