This blog is a preview of our 2022 Crypto Crime Report. Sign up here to download your copy now!

When it comes to cryptocurrency theft, industry observers tend to focus on attacks against large organizations — namely hacks of cryptocurrency exchanges or ransomware attacks against critical infrastructure. But over the last few years, we’ve observed hackers using malware to steal smaller amounts of cryptocurrency from individual users.

Using malware to steal or extort cryptocurrency is nothing new. In fact, nearly all ransomware strains are initially delivered to victims’ devices through malware, and many large-scale exchange hacks also involve malware. But these attacks take careful planning and skill to pull off, as they’re typically targeted against deep-pocketed, professional organizations and, if successful, require hackers to launder large sums of cryptocurrency. With other types of malware, less sophisticated hackers can take a cheaper “spray-and-pray” approach, spamming millions of potential victims and stealing smaller amounts from each individual tricked into downloading the malware. Many of these malware strains are available for purchase on the darknet, making it even easier for less sophisticated hackers to deploy them against victims.

We’re equipping our partners in law enforcement, compliance, and cybersecurity to combat this problem by adding a new tag for malware operator addresses in all Chainalysis products. Below, we’ll examine trends in hackers’ usage of cryptocurrency-focused malware over the last decade and share two case studies to help you understand this under-discussed area of crypto crime.

Malware and cryptocurrency summarized

Malware refers to malicious software that carries out harmful activity on a victim’s device, usually without their knowledge. Malware-powered crime can be as simple as stealing information or money from victims, but can also be much more complex and grand in scale. For instance, malware operators who have infected enough devices can use those devices as a botnet, having them work in concert to carry out distributed denial-of-service (DDOS) attacks, commit ad fraud, or send spam emails to spread the malware further.

The malware families we discuss here are all used to steal cryptocurrency from victims, though some of them are used for other activities as well. The grid below breaks down the most common types of cryptocurrency-focused malware families.

| Type | Description | Example |

| Info stealers | Collect saved credentials, files, autocomplete history, and cryptocurrency wallets from compromised computers. | Redline |

| Clippers | Can insert new text into the victim’s clipboard, replacing text the user has copied. Hackers can use clippers to replace cryptocurrency addresses copied into the clipboard with their own, allowing them to reroute planned transactions to their own wallets. | HackBoss |

| Cryptojackers | Makes unauthorized use of victim device’s computing power to mine cryptocurrency. | Glupteba |

| Trojans | Virus that looks like a legitimate program but infiltrates victim’s computer to disrupt operations, steal, or cause other types of harm. | Mekotio banking trojan |

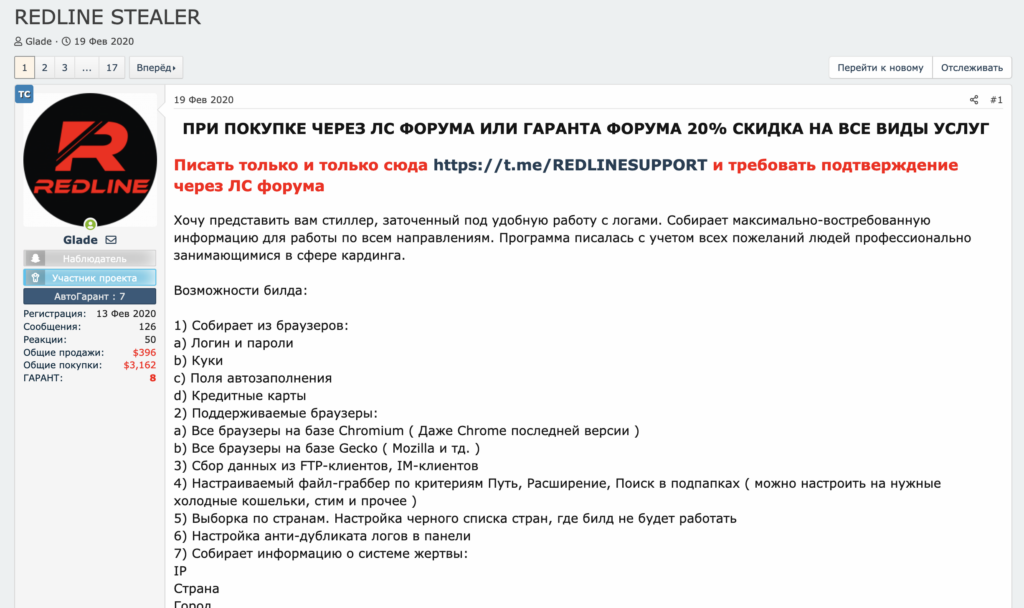

Many of the malware families described above are available to purchase for relatively little money on cybercriminal forums. For instance, the screenshots below show an advertisement for Redline, an info stealer malware, posted on a Russian cybercrime forum.

The seller offers cybercriminals one month of Redline access for $150 and lifetime access for $800. Buyers also get access to Spectrum Crypt Service, a Telegram-based tool that allows cybercriminals to encrypt Redline so that it’s more difficult for victims’ antivirus software to detect it once it’s been downloaded. The proliferation of cheap access to malware families like Redline means that even relatively low-skilled cybercriminals can use them to steal cryptocurrency. Law enforcement and compliance teams must keep this in mind, and understand that the malware attacks they investigate aren’t necessarily carried out by the administrators of the malware family itself, but instead are often carried out by smaller groups renting access to the malware family, similar to ransomware affiliates.

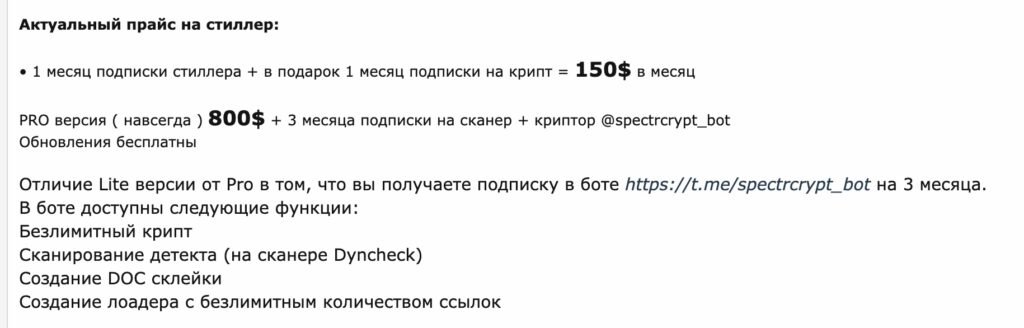

The graph below shows the number of victim transfers to cryptocurrency addresses associated with a sample of malware families in the info stealer and clipper categories investigated by Chainalysis.

Note: This graph does not reflect activity by cryptojackers or ransomware.

Overall, the malware families in this sample have received 5,574 transfers from victims in 2021, up from 5,447 in 2020.

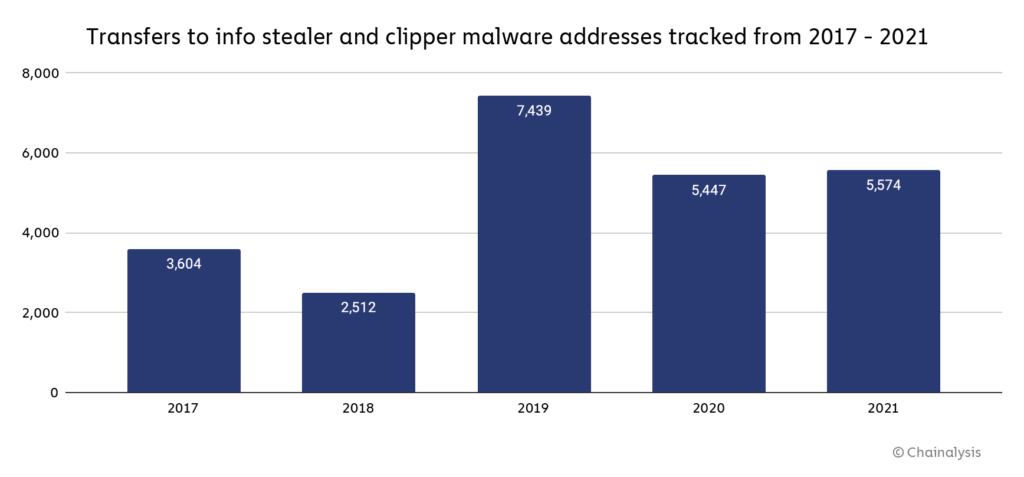

Which malware families were most active?

Note: This graph does not reflect activity by cryptojackers or ransomware.

Cryptbot, an infostealer that takes victims’ cryptocurrency wallet and account credentials, was the most prolific malware family in the group, raking in almost half a million dollars in pilfered Bitcoin. Another prolific family is QuilClipper, a clipboard stealer or “clipper,” ranked eighth on the graph above. Clippers can be used to insert new text into the “clipboard” that holds text a user has copied, usually with the intent to paste elsewhere. Clippers typically use this functionality to detect when a user has copied a cryptocurrency address to which they intend to send funds — the clipper malware effectively hijacks the transaction by then substituting an address controlled by the hacker for the one copied by the user, thereby tricking the user into sending cryptocurrency to the hacker.

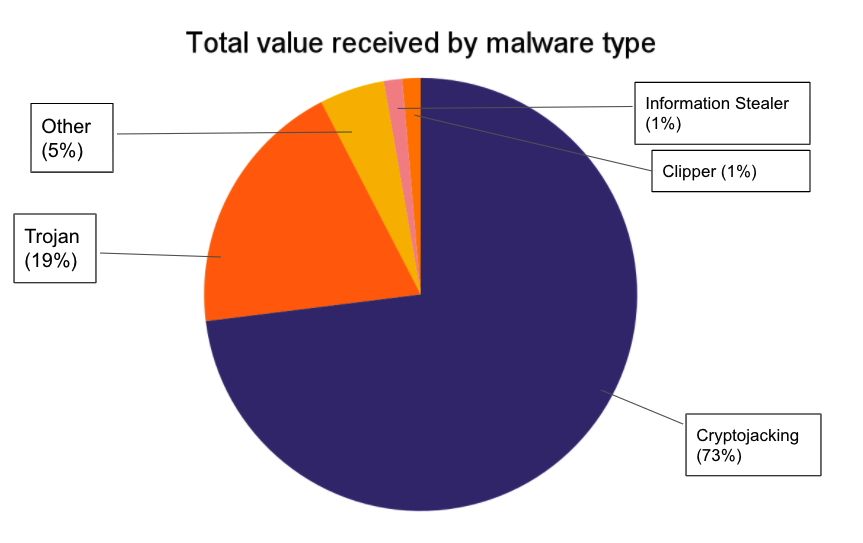

However, none of those numbers reflect totals from what we believe to be the most prolific type of cryptocurrency-focused malware: Cryptojackers.

Cryptojacker activity is murky but substantial

Cryptojackers obtain funds for malware operators by utilizing the victim’s computing power to mine cryptocurrency — usually Monero, but we’ve seen Zcash and Ethereum mined as well. Since funds are moving directly from the mempool to mining addresses unknown to us, rather than from the victim’s wallet to a new wallet, it’s more difficult to passively collect data on cryptojacking activity the way we can other forms of cryptocurrency-based crime. However, we know it’s a big problem. In 2020, Cisco’s cloud security division reported that cryptojacking malware affected 69% of its clients, which would translate to an incredible amount of stolen computer power, and therefore a significant amount of illicitly-mined cryptocurrency. A 2018 report from Palo Alto Networks estimated that 5% of all Monero in circulation was mined by cryptojackers, which would represent over $100 million in revenue, making cryptojackers the most prolific form of cryptocurrency-focused malware.

These numbers are likely only scratching the surface for cryptojacking. As we identify more malware families involved in this activity, we expect to learn that total revenue for the category is even bigger than it currently appears.

Malware and money laundering

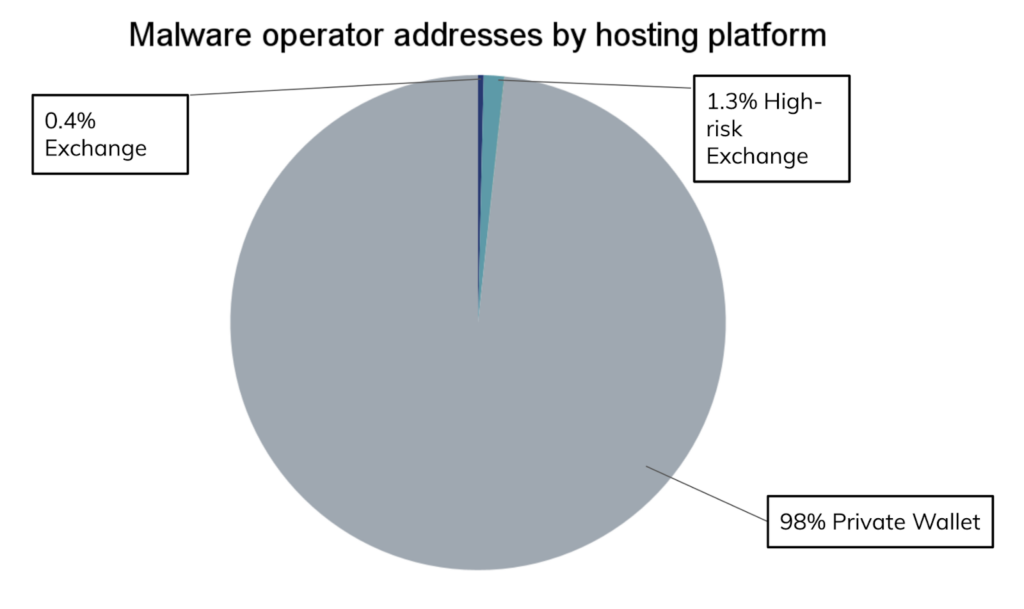

The vast majority of malware operators receive initial victim payments at private wallet addresses, though a few use addresses hosted by larger services. Of that smaller group, the majority use addresses hosted by exchanges — mostly high-risk exchanges that have low or no KYC (Know Your Customer) requirements.

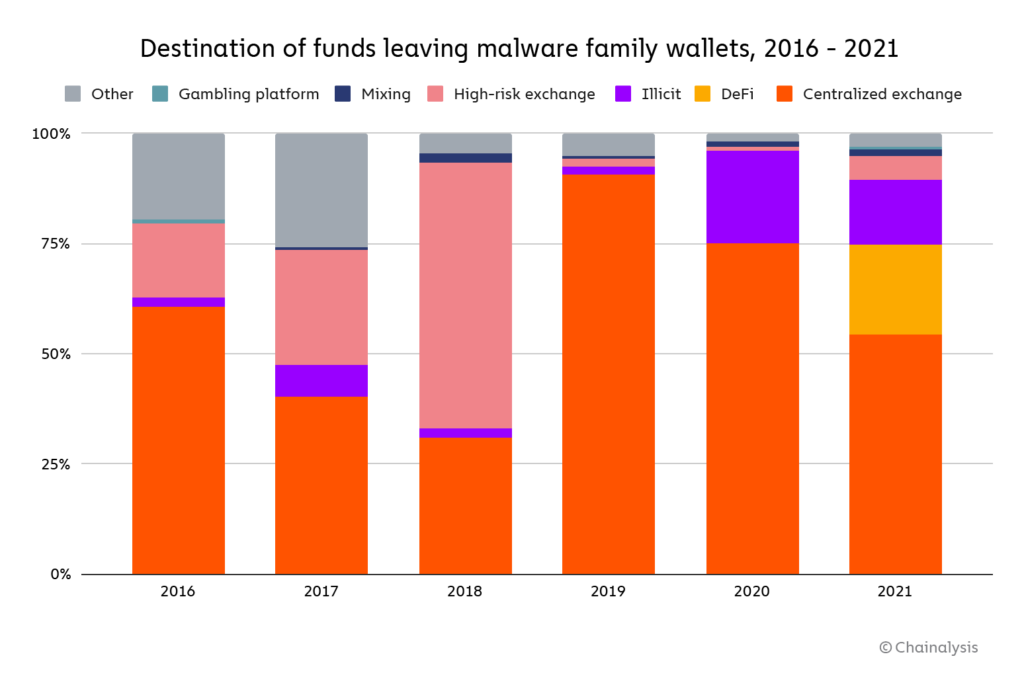

After receiving cryptocurrency from victims, malware operators then send the majority of funds on to addresses at centralized exchanges.

However, that majority is slim and getting slimmer. Exchanges only received 54% of funds sent from malware addresses in 2021, down from 75% in 2020. DeFi protocols make up much of the difference at 20% in 2021, after having received a negligible share of malware funds in 2020. Illicit services seemingly unrelated to malware — mostly darknet markets — are also a significant money laundering avenue for malware operators, having received roughly 15% of all funds sent from malware addresses in 2021.

Malware-based cryptocurrency theft is difficult to investigate in part due to the large number of less sophisticated cybercriminals who can rent access to these malware families. But studying how cybercriminals launder stolen cryptocurrency may be investigators’ best bet for finding those involved. Using blockchain analysis, investigators can follow the funds, find the deposit addresses cybercriminals use to cash out, and subpoena the services hosting those addresses to identify the attackers.

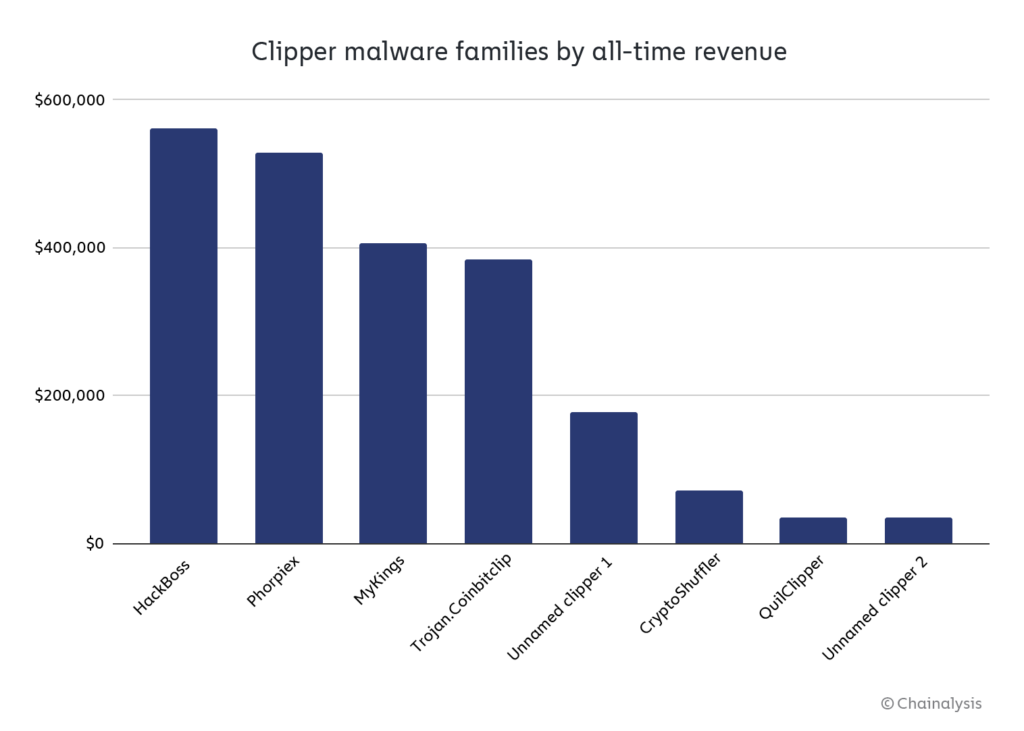

Investigating the HackBoss clipper

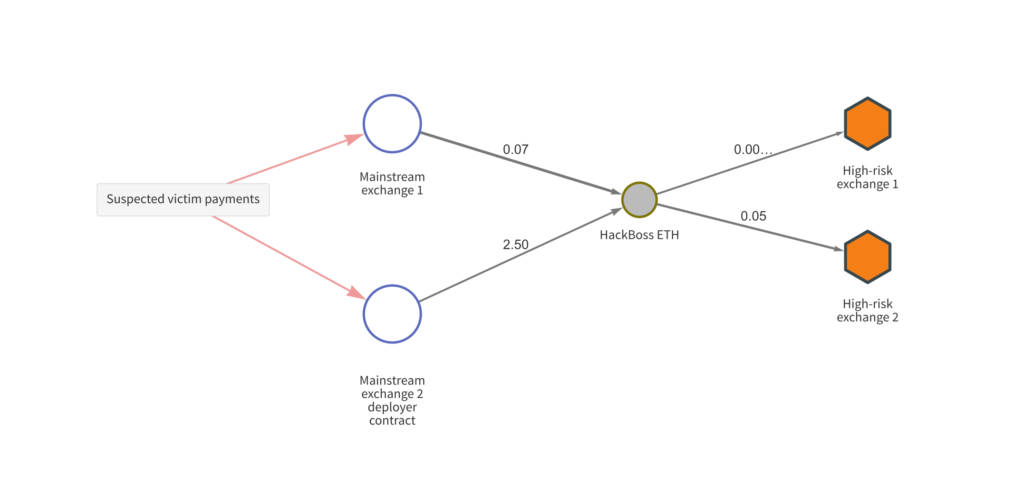

According to Chainalysis data, the HackBoss clipper stole over $80,000 worth of cryptocurrency throughout 2021. Since 2012, HackBoss has been the most prolific clipper malware overall, having taken over $560,000 from victims in assets like Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple, and more.

Interestingly, HackBoss is targeted at fellow hackers rather than what we think of as ordinary victims. According to reporting from Avast.io’s Decoded, HackBoss is distributed through a Telegram channel that purports to provide hacking tools such as social media site crackers. However, instead of those tools, the channel’s users are actually downloading the HackBoss clipper, which steals cryptocurrency from them by inserting its own addresses into the clipboard when victims attempt to copy and paste another address to carry out a cryptocurrency transaction.

The Chainalysis Reactor graph above shows HackBoss receiving cryptocurrency from victims on the left. From there, the malware operators move funds to deposit addresses hosted by high-risk exchanges.

While HackBoss is uniquely targeted at hackers attempting to download tools to carry out their own cybercrimes, most other clippers are targeted at ordinary cryptocurrency users. It’s extremely difficult to know if one has fallen victim to a clipper until a transaction has been hijacked given how long and complex cryptocurrency addresses are — most people don’t read through the recipient’s entire address between pasting it into their wallet and sending a transaction. However, that may be necessary for users trying to be as careful as possible. At the very least, cryptocurrency users need to be vigilant about what links they click and programs they download, as there are several active malware strains — not just clippers, but others too — attempting to steal their funds.

Case study: Glupteba botnet hijacks computers to mine Monero and harnesses the Bitcoin blockchain to evade shutdown

A complaint filed by Google in late 2021 named multiple Russian nationals and entities alleged to be responsible for operating the Glupteba botnet, which has compromised over 1 million machines. Glupteba’s operators have used these machines for several criminal schemes, including utilizing their computing power to mine cryptocurrency — specifically, in this case, Monero — in a practice known as cryptojacking.

Perhaps most notable is Glupteba’s use of the Bitcoin blockchain to withstand attempts to take it offline, encoding updated command-and-control servers (C2) into the Op_Returns of Bitcoin transactions. Google used Chainalysis software and Chainalysis Investigative Services to analyze the Bitcoin addresses and transactions responsible for sending updated C2 instructions. Below, we’ll break down how the Glupteba botnet uses the Bitcoin blockchain to defend itself and what it means for cybersecurity and law enforcement.

A primer on the Glupteba botnet

The cybercriminals behind the Glupteba botnet have used it to carry out a variety of criminal schemes. In addition to cryptojacking, the botnet has been used to acquire and sell Google account information stolen from infected machines, commit digital advertising fraud, and sell stolen credit card data.

Google was able to identify the individuals named in the complaint by obtaining and examining an IP address used by one of Glupteba’s C2 servers. All individuals were also listed as owners or administrators of shell companies connected to Glupteba-related crimes, such as one used to sell fraudulent digital advertising impressions supplied by the botnet. Google was able to successfully take down the current C2 server, however as Glupteba has proven to be infallible against these actions through it’s blockchain failsafe, we will soon see a new C2 assigned.

How Glupteba weaponizes the blockchain

In order to direct botnets, cybercriminals rely on command-and-control (C2) servers, which allow them to send commands to machines infected with malware. Botnets look for domain addresses controlled by their C2 servers in order to receive instructions, with directions on where to look for those domain addresses hard coded into the malware itself.

In order to combat botnets, law enforcement and cybersecurity professionals try to take those domains offline so that the botnets can no longer receive instructions from the C2 server. In response, botnet operators typically set up a number of backup domains in case the active domain is taken down. Most malware algorithmically generates new domain addresses for botnets to scan until they find one of those backups, allowing them to receive new instructions from the C2 server.

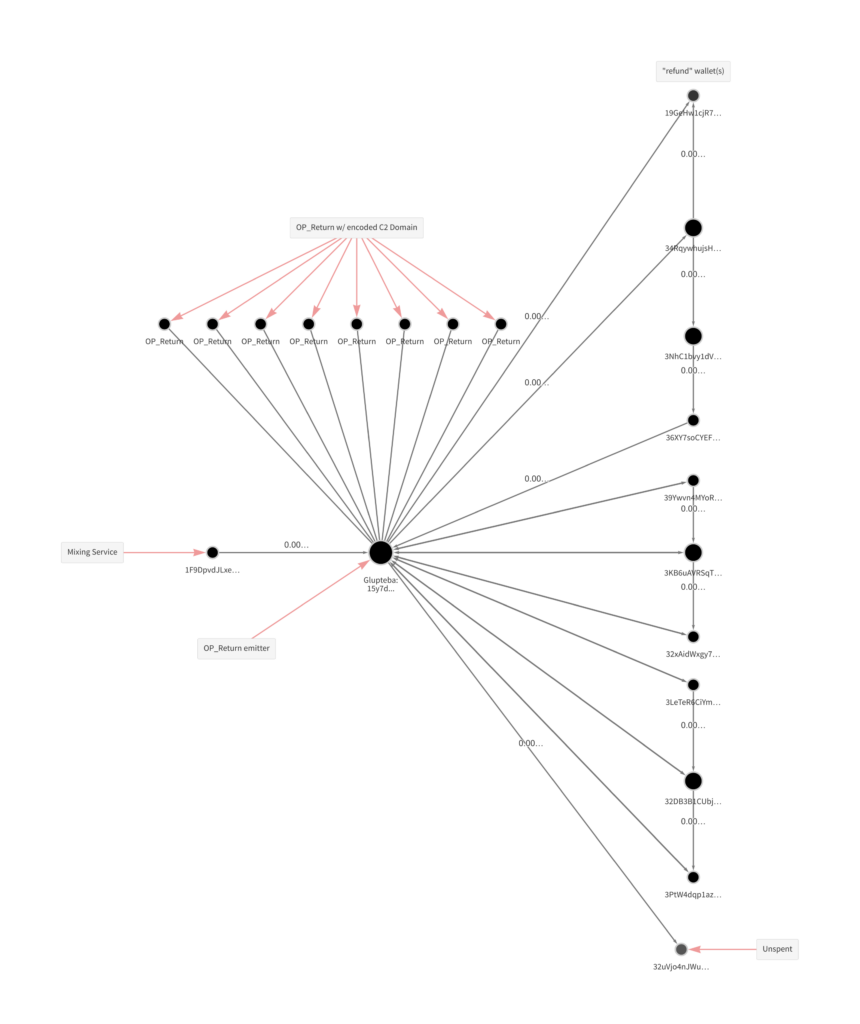

However, Glupteba does something new. When its C2 server is disrupted, Glupteba is programmed to search the Bitcoin blockchain for transactions carried out by three addresses controlled by its operators. Those addresses carry out transactions of little or no monetary value, with encrypted data written into the transaction’s Op_Return field, which is used to mark transactions as invalid. Glupteba malware can then decode the data entered into the Op_Return field to obtain the domain address of a new C2 server.

In other words, whenever one of Glupteba’s C2 servers is shut down, it can simply scan the blockchain to find the new C2 server domain address, hidden amongst hundreds of thousands of daily transactions. This tactic makes the Glupteba botnet extremely difficult to disrupt through conventional cybersecurity techniques focused on disabling C2 server domains. This is the first known case of a botnet using this approach.

Here’s what we know about the three Bitcoin addresses we’ve identified as being used by Glupteba’s operators to keep the botnet online:

| Address | Dates active | Number of transfers | Number of Op_Returns |

| 15y7dskU5TqNHXRtu5wzBpXdY5mT4RZNC6 | 6/17/2019 – 5/13/2020 | 32 | 8 |

| 1CgPCp3E9399ZFodMnTSSvaf5TpGiym2N1 | 4/8/2020 – 10/19/2021 | 16 | 6 |

| 1CUhaTe3AiP9Tdr4B6wedoe9vNsymLiD97 | 10/13/21 – present | 18 | 6 |

Combined, the three addresses have only transacted a few hundred dollars’ worth of Bitcoin, but the messages encoded into the Op_Returns on some of those transactions have helped the Glupteba botnet remain operational. Let’s look more closely at address 157d… in Chainalysis Reactor as an example.

We see that the Glupteba address received its initial funding from a mixing service, before initiating the invalid transactions with Op_Returns we see at the top of the graph. The funds associated with those invalid transactions then travel to the refund wallets on the right, and eventually back to the original Glupteba address. The other two addresses show similar transaction patterns. Google identified the three Glupteba addresses and brought them to Chainalysis, at which point our investigators were able to decode the data contained in the Op_Returns’ message fields, allowing them to discover the new C2 server domain addresses being sent to the botnet.

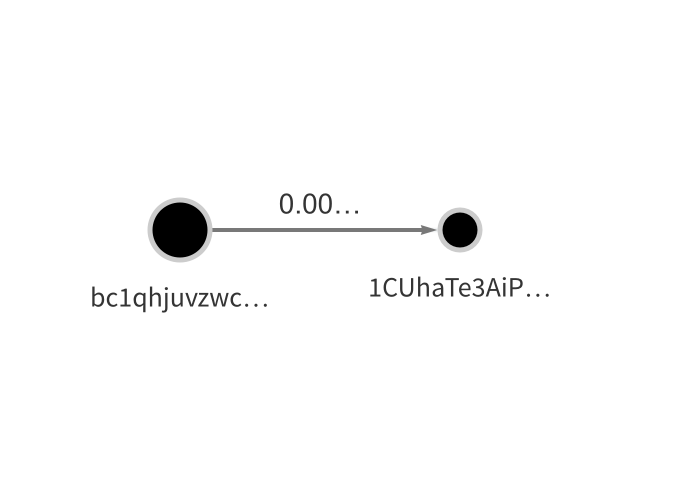

Like address 15y7d…, address 1CgPC… was initially funded through outputs from mixing transactions. However, the third address, 1Cuha…, received initial funding from another private wallet address: bc1qhjuvzwcv0pp68kn2sqvx3d2k3pqfllv3c4vywd.

Interestingly, other transactions sent by bc1qh… have been associated with Federation Tower, a luxury office building in Moscow that also housed Suex, a now-sanctioned cryptocurrency OTC broker involved in money laundering for several forms of cybercrime, including ransomware. Reporting from Bloomberg and The New York Times discusses other cryptocurrency businesses headquartered in Federation Tower, including EggChange, an exchange that’s also been linked to cybercrime and whose founder, Denis Dubnikov, was arrested by U.S. authorities in November 2021. These links raise more questions about the interconnectedness of illicit, Russia-based cryptocurrency businesses associated with malware and ransomware attacks.

Glupteba shows why all cybersecurity teams need to understand cryptocurrency and blockchain analysis

Glupteba’s blockchain-based method of avoiding the shutdown of its botnet represents a never-before-seen threat vector for cryptocurrencies. In the private sector, cryptocurrency businesses and financial institutions have thus far typically been the ones tackling cases involved in blockchain analysis, usually from an AML/CFT compliance perspective. But this case shows that cybersecurity teams at virtually any company that could be a target for cybercriminals — especially those possessing large amounts of sensitive customer data — must be well-versed in cryptocurrency and blockchain analysis in order to stay ahead of cybercriminals. At Chainalysis, we’re eager to work with those teams to help them understand how our tools can assist them in diagnosing and fighting these threats, so that cryptocurrencies can’t be weaponized against them or their users.

The convergence of malware and cryptocurrency: Same cybercriminals, new methods

The cybersecurity industry has been dealing with malware for years, but the usage of these malicious programs to steal cryptocurrency means cybersecurity teams need new tools in their toolbox. Chainalysis gives cybersecurity teams new avenues of investigation for malware, allowing them to take advantage of blockchains’ transparency and track the movement of funds that have been stolen until they reach an address whose owner can be identified. Likewise, cryptocurrency compliance teams already well-versed in blockchain analysis must educate themselves on malware in order to ensure these threat actors aren’t taking advantage of their platforms to launder stolen cryptocurrency.

This blog is a preview of our 2022 Crypto Crime Report. Sign up here to download your copy now!

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making investment decisions.

This website contains links to third-party sites that are not under the control of Chainalysis, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Chainalysis”). Access to such information does not imply association with, endorsement of, approval of, or recommendation by Chainalysis of the site or its operators, and Chainalysis is not responsible for the products, services, or other content hosted therein.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.